ABSTRACT

Acute hepatitis A is usually self-limited, yet a minority develop prolonged cholestasis with severe jaundice and pruritus that prolong hospitalization and impair quality of life. Evidence for systemic corticosteroids remains limited. We report a steroid-responsive case. A previously healthy 30-year-old Korean woman presented with seven days of fever and malaise and was diagnosed with acute hepatitis A. Despite supportive care, marked cholestasis persisted while aminotransferases stabilized. Imaging examinations excluded bile duct obstruction and autoimmune serologies were negative. On hospital day 25, prednisolone 1 mg/kg was commenced, and following corticosteroid initiation, pruritus and jaundice improved within days, with a progressive decline in bilirubin, and the dose was tapered without biochemical rebound. Systemic corticosteroids may constitute an effective short-term therapeutic option for prolonged cholestasis secondary to acute hepatitis A after exclusion of alternative etiologies and with appropriate infection risk assessment.

-

KEYWORDS: Hepatitis A; Cholestasis; Treatment; Prednisolone; Jaundice

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) remains a common cause of acute viral hepatitis worldwide and is typically self-limited [

1]. A minority of patients develop a prolonged cholestatic phenotype characterized by intense jaundice and intractable pruritus that can persist for weeks or months despite improvement of aminotransferases [

2,

3]. This pattern imposes substantial symptom burden (severe pruritus), sleep disruption, and reduced quality of life, and often leads to repeated hospital visits. The pathophysiology is believed to involve inflammation-mediated impairment of canalicular bile transporters and intrahepatic cholestasis rather than extrahepatic obstruction [

4,

5].

Management is largely supportive, with emphasis on hydration, nutrition, avoidance of hepatotoxic exposures, and targeted symptom and biochemical control. Bile acid sequestrants, ursodeoxycholic acid, rifampin, and antihistamines are frequently utilized, yet many patients experience inadequate relief. Small case series and reports have described clinical and biochemical improvement with short courses of systemic corticosteroids in selected patients with severe or prolonged cholestasis after exclusion of alternative etiologies such as autoimmune hepatitis, drug-induced liver injury, and extrahepatic obstruction [

3,

6,

7]. The hypothesized benefit derives from modulation of immune-mediated dysfunction and reduction of cytokine-driven impairment of bile excretion. Steroid therapy warrants attention to timing, dosing, tapering, and safety monitoring, particularly in the presence of intercurrent infection.

We describe a young adult with acute hepatitis A and prolonged cholestasis who exhibited rapid symptomatic and laboratory improvement following initiation of systemic corticosteroids. The case highlights practical diagnostic thresholds, clinical decision points, and safeguards that can inform management when the cholestatic course fails to resolve with conservative measures.

CASE

A previously healthy 30-year-old Korean woman presented to our emergency department with seven days of fever, chills, malaise, and progressive jaundice. Her medical history included Graves’ disease diagnosed two years earlier, with dysthyroid exophthalmos for one year, managed with methimazole prior to admission. She denied hypertension, diabetes, or prior liver disease. She consumed approximately 10 g of alcohol per day and was a never-smoker. Family history was notable for hepatocellular carcinoma in her grandfather and liver cirrhosis in her sister. She had traveled to a valley region three weeks before presentation and reported ingestion of marinated crab three and five weeks prior, as well as sashimi on five occasions over the previous two months. On arrival, vital signs were blood pressure 150/90 mmHg, temperature 37.7°C with a reported peak of 40°C, heart rate 92 beats per minute, and respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute. Physical examination revealed acute ill appearance and icteric sclerae; the chest was clear to auscultation, the abdomen was soft and nontender with normal bowel sounds, and there was no peripheral edema. Risk assessment disclosed no high-risk sexual exposure, no contact with jaundiced persons, and no history of injection-drug use, surgery, blood transfusion, or accidental needle-stick.

She had been hospitalized at an another hospital for four days because of fever and chills, but developed worsening nausea and vomiting with deterioration of liver tests, prompting transfer to our institution. On hospital day (HD) 1 at our center, laboratory results showed aspartate aminotransferase 2,447 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 1,297 U/L, total bilirubin 6.01 mg/dL, and direct bilirubin 4.19 mg/dL; anti-HAV IgM was positive, confirming acute hepatitis A. Chest and abdominal radiographs and contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography were unremarkable.

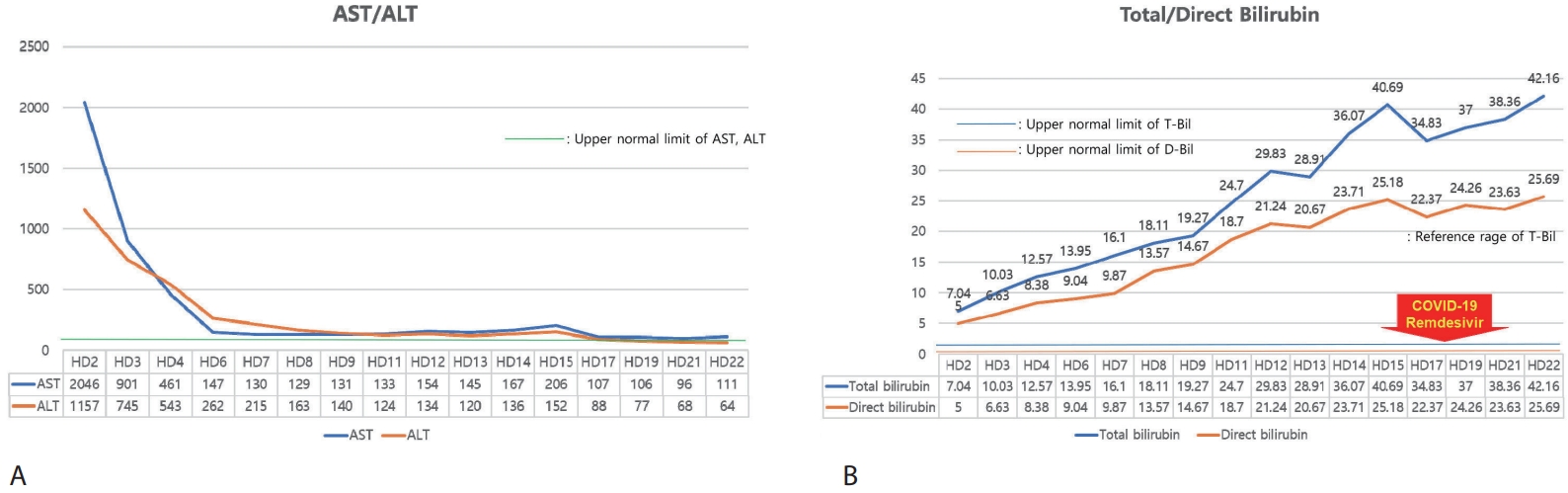

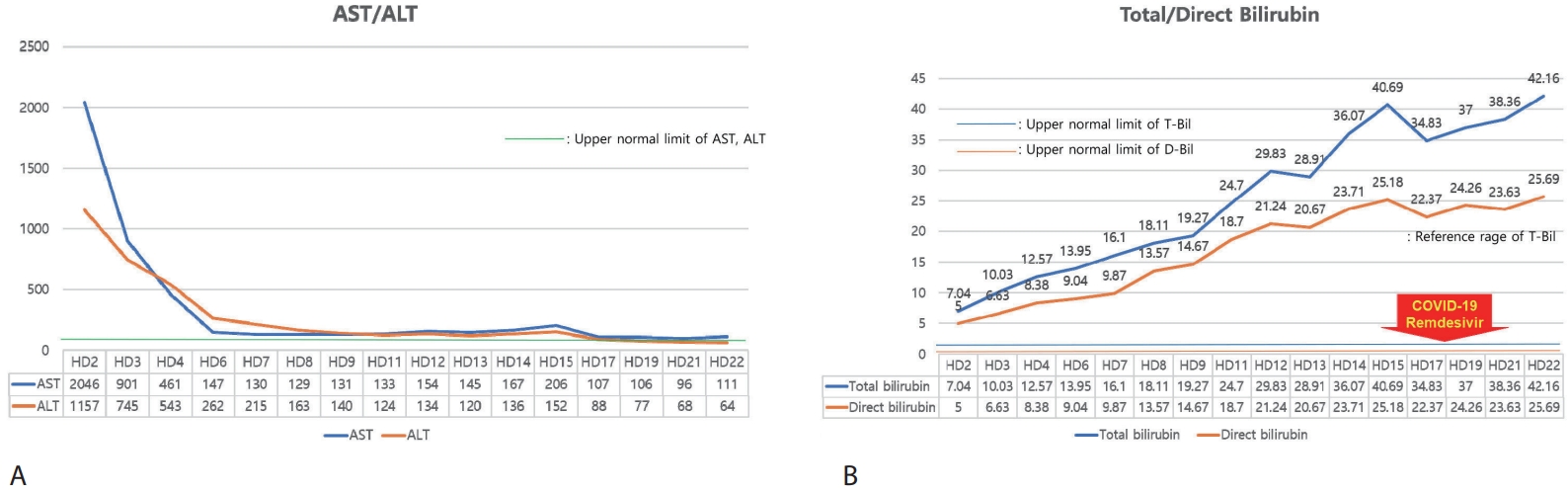

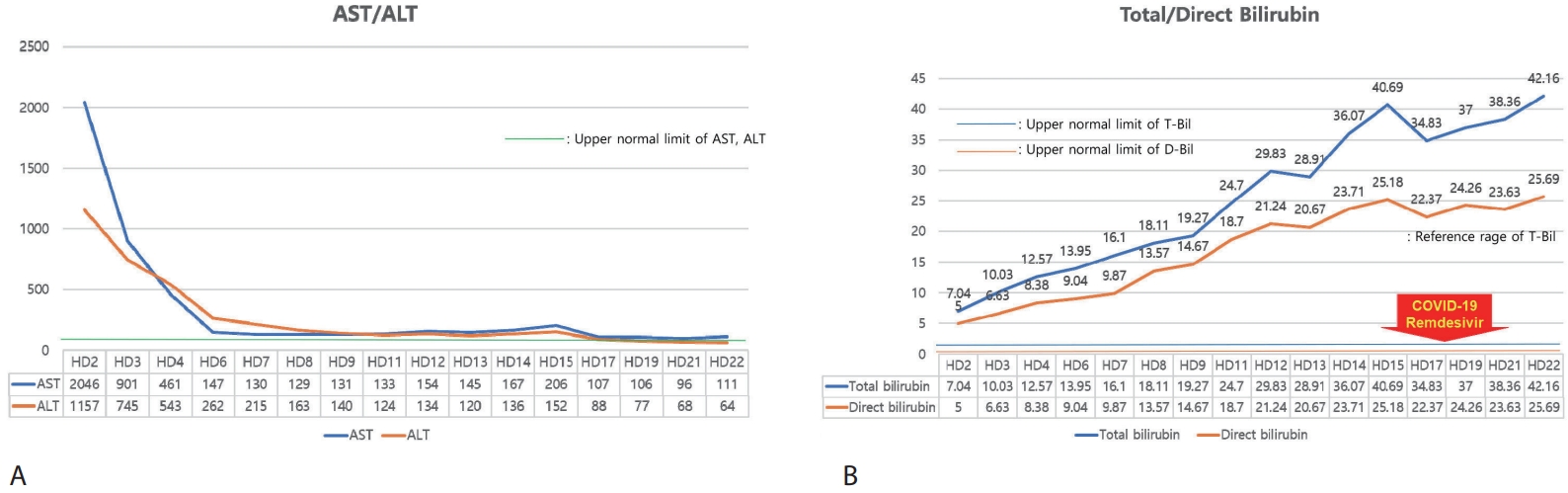

After hospitalization for intravenous hydration and supportive care with hepatoprotective agents, serum aminotransferases showed a marked decline (

Fig. 1A); however, total bilirubin continued to rise (

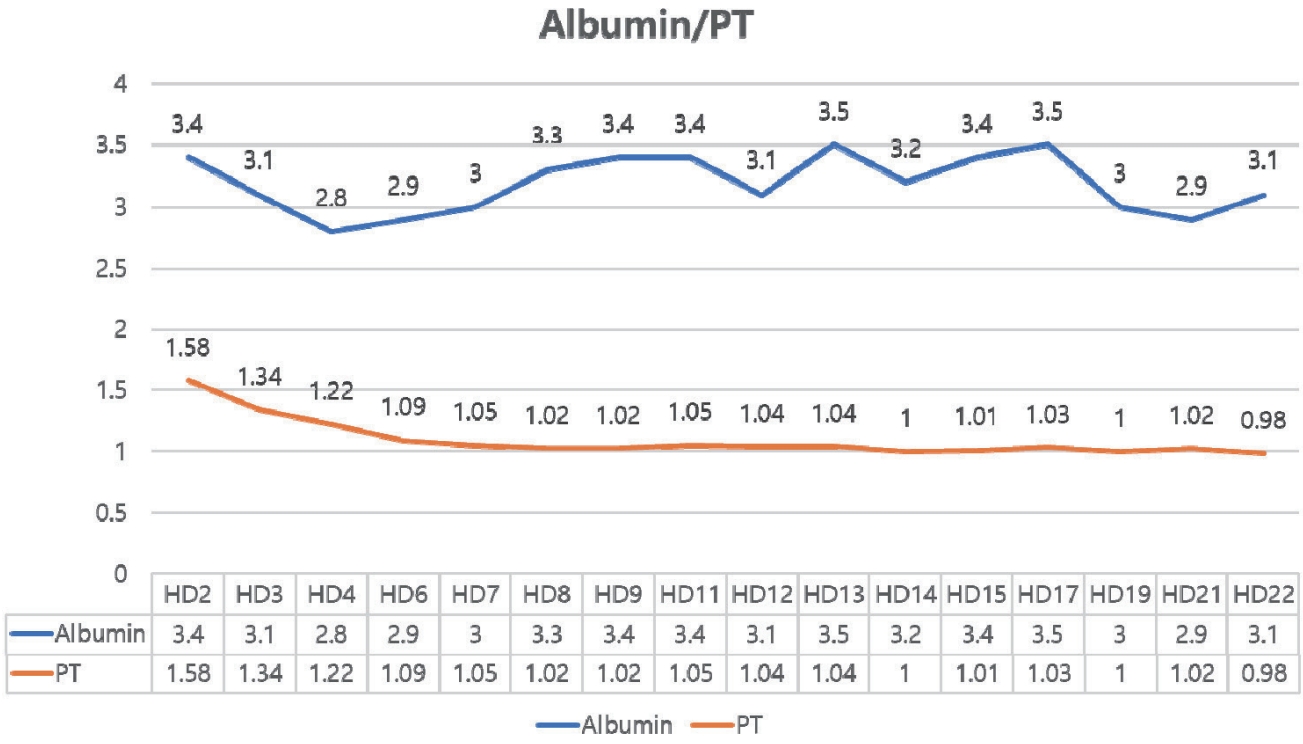

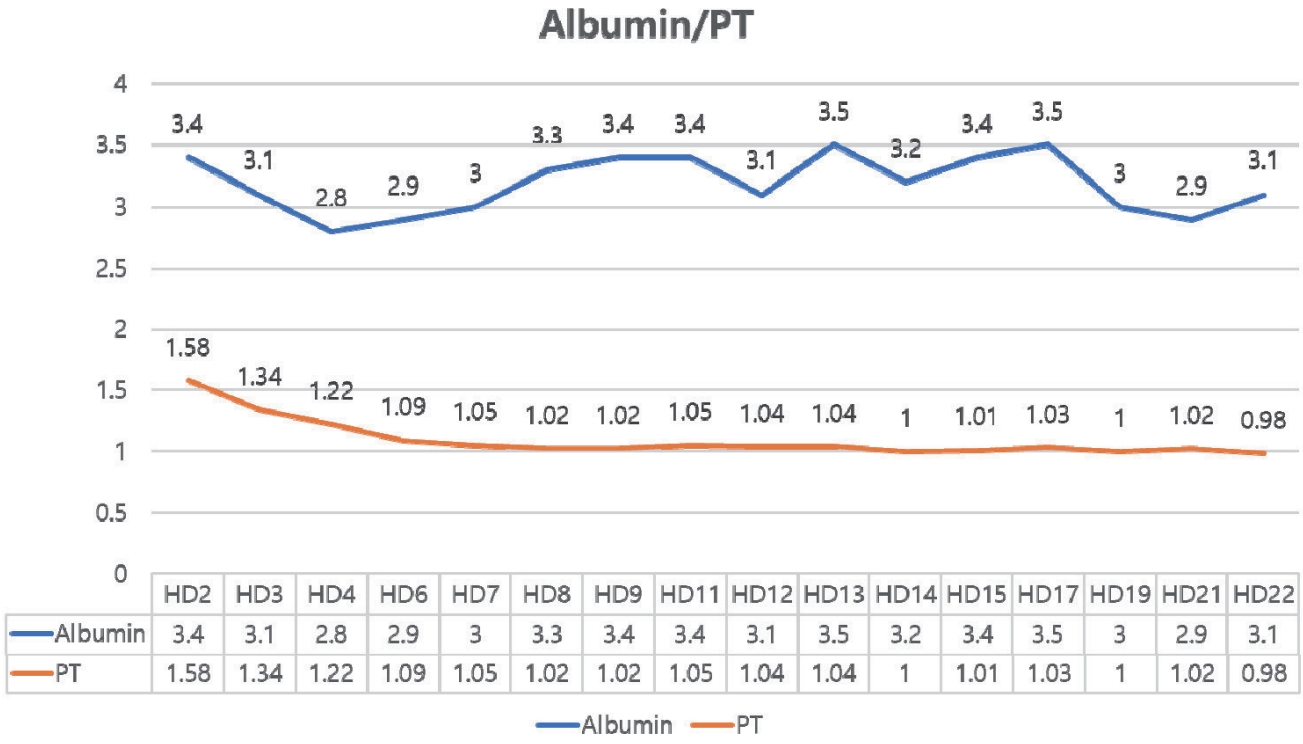

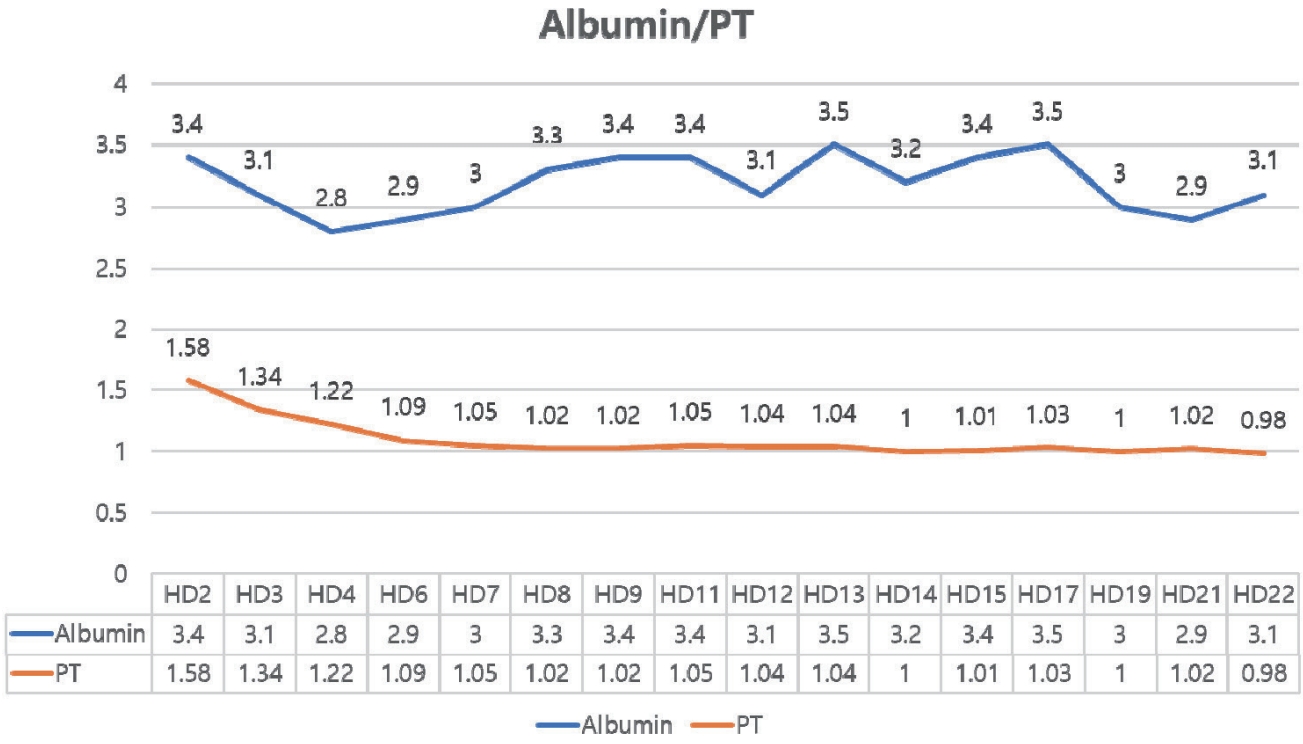

Fig. 1B). On HD 17, bilirubin decreased slightly, but she was diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19). Although COVID-19 resolved without complication following a three-day course of remdesivir, the bilirubin level rose again. Throughout this period, hepatic synthetic function remained preserved, with normal prothrombin time and albumin (

Fig. 2). Given the persistent, protracted hyperbilirubinemia and pruritus refractory to supportive measures, with infectious and autoimmune cases reasonably excluded on serial evaluation, we initiated systemic corticosteroid therapy (prednisolone) on HD 25. Additionally, the patients had no COVID-19 related symptoms and given that systemic steroid are utilized for treatment in severe COVID-19, the risk-benefit was deemed acceptable. Prednisolone was initiated at 60 mg/day (approximately 1 mg/kg), and following initiation of prednisolone, pruritus subsided within several days and jaundice began to regress. Serial liver tests showed stepwise declines in total bilirubin alongside symptomatic improvement (

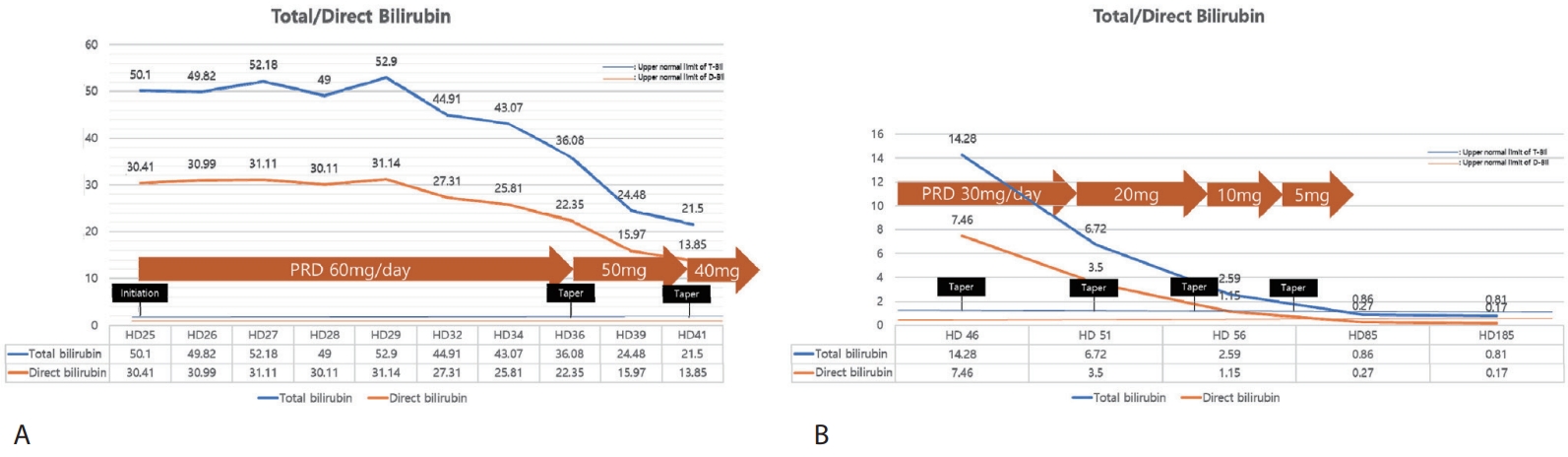

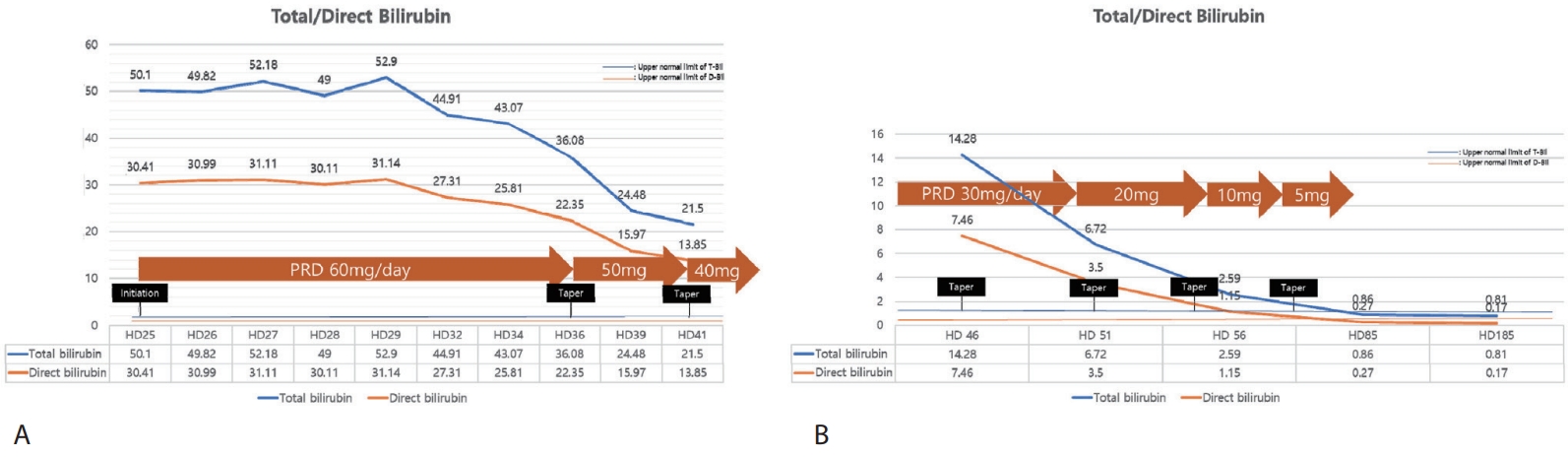

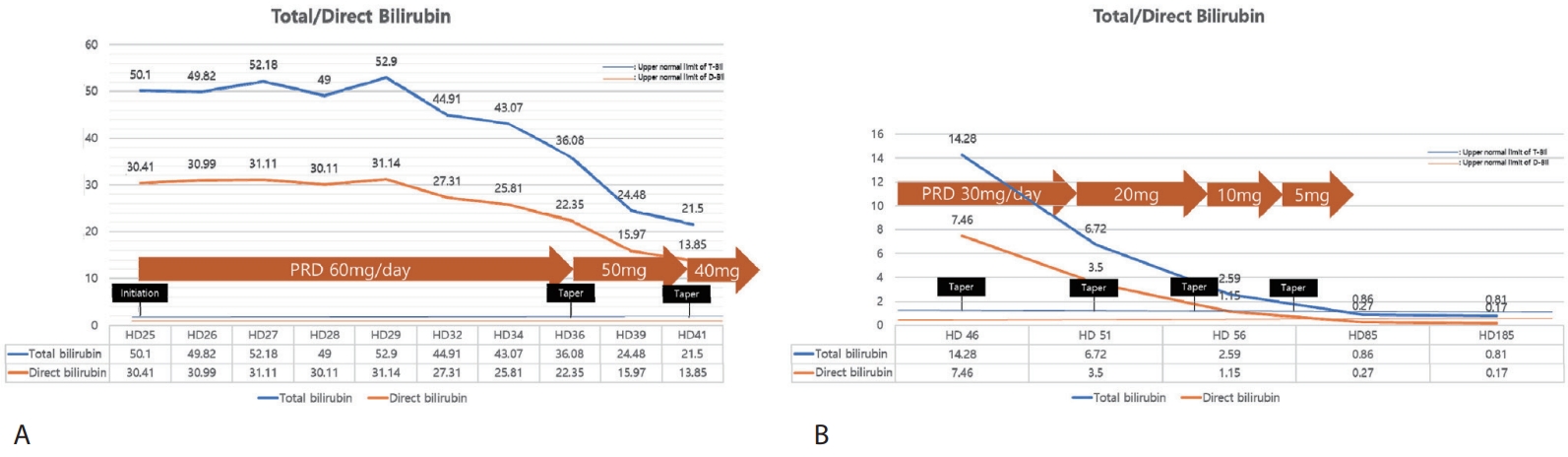

Fig. 3). The steroid dose was tapered from 60 mg/day to 50 mg and 40 mg during hospitalization, then to 30 mg, 20 mg, 10 mg, and 5 mg as an outpatient, without biochemical rebound or infectious complications. Serial results during and after the taper were consistent with progressive resolution of cholestasis. At last follow-up visit, she was asymptomatic and liver biochemistries had normalized and transient elastography showed minimal fibrosis (F0) and mild steatosis (S1).

DISCUSSION

Acute hepatitis A virus infection remains a globally important cause of acute viral hepatitis [

4]. In most cases the illness is self-limited, with spontaneous resolution of jaundice and constitutional symptoms over several weeks. Clinical severity increases with age, and adults are more likely than children to experience symptomatic disease and higher peaks of bilirubin and aminotransferases. Uncommon but recognized atypical patterns include relapsing hepatitis, prolonged cholestasis, extrahepatic complications such as acute kidney injury, and drug-related hypersensitivity syndromes that may confound the course. As anti HAV seroprevalence declines, the adult burden of symptomatic hepatitis A increases and atypical presentations become more frequent [

8]. These observations frame our case of a young adult with acute HAV. The course was dominated by prolonged cholestasis and debilitating pruritus despite stabilization of aminotransferases. The patient improved after a carefully selected course of systemic corticosteroids.

The cholestatic phenotype of acute HAV is characterized by persistent hyperbilirubinemia out of proportion to hepatocellular enzyme activity in the absence of extrahepatic obstruction on imaging. Operational definitions in the literature include a peak total bilirubin greater than 10 mg/dL with the direct fraction exceeding 50 percent of total and jaundice lasting beyond twelve weeks once hemolysis and renal failure are excluded [

5]. Although the natural history is usually benign, symptoms such as pruritus, anorexia, and fatigue may be profound and protracted, with substantial impairment in daily function and quality of life. Prolonged cholestasis is thought to reflect an inflammation-mediated intrahepatic secretory failure rather than mechanical obstruction. Experimental and translational data support a cytokine-driven process in which tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1 downregulate canalicular export pumps, particularly multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2), with resulting impairment of bilirubin and bile acid excretion. In addition, endotoxin signaling and changes in canalicular transporter expression contribute to reduced bile flow [

9]. Genetic and viral factors may modulate risk and severity, including differences in HAV genotypes and polymorphisms in hepatocanalicular transporters [

3]. These concepts provide a biologic rationale for anti-inflammatory strategies when conservative measures fail.

Systemic corticosteroids have been used empirically in cholestatic HAV to curb inflammation, relieve pruritus, and accelerate bilirubin decline after exclusion of competing etiologies such as autoimmune hepatitis, drug-induced liver injury, and extrahepatic obstruction. In a Korean case series of three adults with severely cholestatic HAV, prednisolone 30 mg was started after weeks of persistent hyperbilirubinemia and negative imaging for obstruction. All three showed rapid symptomatic improvement and a prompt fall in total bilirubin, with taper over six to ten weeks and no infectious complications [

3]. Histology demonstrated lobular inflammation with intrahepatic cholestasis but no ductular destruction, aligning with a non-obstructive secretory defect. Our patient’s course parallels these reports but with a weight-based starting dose of 1 mg/kg and bilirubin guided taper, without biochemical rebound. Additional case-based evidence includes two reports in which prednisolone given as a prolonged taper or as short “pulsed” doses produced rapid relief of pruritus and a fall in bilirubin within days, underscoring that symptom control and biochemical recovery can occur with different dosing strategies when selection is judicious [

7]. In fulminant pediatric HAV, steroids have been associated with improved survival when immune mediated hepatocyte injury predominates [

10]. This indirectly supports a role for immunomodulation across the HAV spectrum, although populations and phenotypes differ. At the same time, clinicians must balance potential benefits against risks. Steroid use in the setting of intercurrent infection can unmask or worsen opportunistic infections and may complicate atypical drug reactions, as illustrated by a DRESS syndrome case with cytomegalovirus reactivation during steroid therapy after cholestatic HAV [

8].

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis is often considered when patients receive prednisone equivalent 20 mg per day or more for 4 weeks or longer, with trimethoprim-sulfomethoxazole (TMP-SMX) as the preferred agent [

11]. However, TMP SMX carries a clinically meaningful risk of liver toxicity, about 10 percent in adult populations, and rare cases progress to acute liver failure [

12,

13]. In our patient with severe cholestatic hepatitis, prednisolone 60 mg per day was initiated and then tapered promptly, limiting the anticipated duration of high dose exposure. After a risk benefit discussion, we did not initiate TMP-SMX prophylaxis and instead monitored closely and the patient remained free of opportunistic infection on follow up. Further studies are needed to clarify the role of TMP SMX prophylaxis in immunocompromised patients with severe liver injury.

In our case, the presence of COVID-19 prompted antiviral management and close monitoring during the steroid course. The clinical response aligns with the pathophysiology of inflammation mediated cholestasis. Cholestasis may arise at several steps of bilirubin handling, including uptake, conjugation, canalicular excretion, and extrahepatic obstruction, but in hepatitis A it largely reflects inflammation mediated intrahepatic secretory failure. Endotoxin and cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1 inhibit MRP2, leading to impaired bilirubin clearance. Systemic steroids may counteract these mediators and restore MRP2 expression [

14,

15]. More broadly, glucocorticoids suppress cytokine pathways that inhibit MRP2 and upregulate transporter expression via glucocorticoid responsive elements in the MRP2 promoter, restoring canalicular export and reducing cholestasis [

16,

17]. These antiinflammatory and transcriptional effects plausibly explain relief of pruritus and faster bilirubin clearance once necroinflammation has subsided.

In summary, prolonged cholestasis is an infrequent yet clinically burdensome variant of acute HAV that may persist despite conservative therapy. When imaging excludes obstruction and laboratory evaluation reduces the likelihood of autoimmune or drug-induced etiologies, a time-limited course of systemic corticosteroids can be considered in carefully selected patients with debilitating pruritus and sustained hyperbilirubinemia, particularly when hepatic synthetic function is preserved. The present case demonstrates rapid symptomatic and biochemical improvement after initiation of prednisolone with weight based dosing and a bilirubin guided taper. In prolonged cholestatic hepatitis A, steroids may be considered after excluding alternative causes, with close monitoring for infection or relapse and use of serial liver tests to guide dose adjustments. Future controlled studies are warranted to define optimal timing, dose, and taper. Meanwhile, decisions should be individualized to symptom burden, bilirubin trajectory, and comorbid risk.

NOTES

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

-

FUND

None.

-

ETHICS STATEMENT

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Yoon JH conceived and designed the study, reviewed the literature, and contributed to manuscript drafting and editing; Cho SB contributed to manuscript revision; all authors issued final approval for the version to be submitted and approved the publication of the manuscript.

Figure 1.Trends in (A) AST/ALT and (B) total/direct bilirubin during hospitalization. AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

Figure 2.Trends of PT (INR) and albumin during hospitalization. PT, prothrombin time; INR, international normalized ratio.

Figure 3.Trends of total/direct bilirubin after systemic steroid treatment; (A) inpatient course and (B) outpatient course. PRD, prednisolone.

REFERENCES

- 1. Xiao W, Zhao J, Chen Y, et al. Global burden and trends of acute viral hepatitis among children and adolescents from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Hepatol Int 2024;18:917-928.

- 2. Coppola N, Genovese D, Pisaturo M, et al. Acute hepatitis with severe cholestasis and prolonged clinical course due to hepatitis A virus Ia and Ib coinfection. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:e73-e77.

- 3. Yoon EL, Yim HJ, Kim SY, et al. Clinical courses after administration of oral corticosteroids in patients with severely cholestatic acute hepatitis A; three cases. Korean J Hepatol 2010;16:329-333.

- 4. Van Damme P, Pinto RM, Feng Z, et al. Hepatitis A virus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2023;9:51.

- 5. Saboo AR, Vijaykumar R, Save SU, Bavdekar SB. Prolonged cholestasis following hepatitis a virus infection: revisiting the role of steroids. J Glob Infect Dis 2012;4:185-186.

- 6. Chirag R, Arun Babu T. Successful treatment of prolonged cholestasis following hepatitis A infection in a child with oral steroid therapy. BMJ Case Rep 2023;16:e257477.

- 7. Daghman D, Rez MS, Soltany A, et al. Two case reports of corticosteroid administration-prolonged and pulsed therapy-in treatment of pruritus in cholestatic hepatitis A patients. Oxf Med Case Rep 2019;2019:omz080.

- 8. An J, Lee JH, Lee H, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome following cholestatic hepatitis A: a case report. Korean J Hepatol 2012;18:84-88.

- 9. Gokce S, Cenesiz F, Ozalp Akin E. Steroid treatment of protracted cholestatic hepatitis A in a child with beta-thalassemia. Turk J Gastroenterol 2014;25:278-279.

- 10. Zakaria HM, Salem TA, El-Araby HA, et al. Steroid therapy in children with fulminant hepatitis A. J Viral Hepat 2018;25:853-859.

- 11. Rhoads S, Maloney J, Mantha A, et al. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in HIV-negative, non-transplant patients: Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Curr Fungal Infect Rep 2024;18:125-135.

- 12. Yang JJ, Huang CH, Liu CE, et al. Multicenter study of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole-related hepatotoxicity: incidence and associated factors among HIV-infected patients treated for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. PLoS One 2014;9:e106141.

- 13. Abusin S, Johnson S. Sulfamethoxazole/Trimethoprim induced liver failure: a case report. Cases J 2008;1:44.

- 14. Trauner M, Fickert P, Stauber RE. Inflammation-induced cholestasis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999;14:946-959.

- 15. Roelofsen H, Schoemaker B, Bakker C, et al. Impaired hepatocanalicular organic anion transport in endotoxemic rats. Am J Physiol 1995;269:G427-G434.

- 16. Kauffmann HM, Schrenk D. Sequence analysis and functional characterization of the 5'-flanking region of the rat multidrug resistance protein 2 (mrp2) gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998;245:325-331.

- 17. Demeule M, Jodoin J, Beaulieu E, et al. Dexamethasone modulation of multidrug transporters in normal tissues. FEBS Lett 1999;442:208-214.