ABSTRACT

Acute hepatitis A is an inflammation of the liver caused by the hepatitis A virus, typically resulting in mild to severe illness from which most individuals recover fully without complications. However, in rare cases, it may lead to long-term sequelae. Secondary hemochromatosis refers to iron overload resulting from various causes, including chronic liver disease, repeated blood transfusions, and systemic inflammation. Here, we report a rare case of secondary hemochromatosis that developed following acute hepatitis A.

-

KEYWORDS: Hemochromatosis; Hepatitis A; Iron overload; Phlebotomy

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) is a single-stranded RNA virus that is encased in the host plasma membrane and circulates in the bloodstream [

1]. After an incubation period of 3–4 weeks in the liver, HAV infection may develop symptoms such as fatigue, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, myalgia, and jaundice. Once jaundice becomes apparent, infectivity declines rapidly, and nearly all previously healthy individuals recover completely without clinical sequelae. However, in rare cases, HAV infection may progress to fulminant hepatitis or result in prolonged liver inflammation.

Hemochromatosis is a disorder of iron metabolism characterized by excessive iron accumulation in parenchymal cells, leading to cellular injury, tissue fibrosis, and eventual organ failure [

2]. The liver is one of the most commonly affected organs, and the presence of jaundice or elevated liver enzymes may raise clinical suspicion for hemochromatosis. Without appropriate treatment, such as phlebotomy or iron chelation therapy, the disease may progress to chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hereditary hemochromatosis is most often caused by mutations in the homeostatic iron regulator (

HFE) gene, which plays a crucial role in iron homeostasis. Acquired forms of iron overload are classified as secondary hemochromatosis and can result from conditions such as iron-loading anemias or chronic liver disease. Several case reports have described secondary hemochromatosis following chronic hepatitis [

3,

4]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no cases of secondary hemochromatosis following acute hepatitis A have been reported.

Here, we describe a rare case of secondary hemochromatosis that developed after an acute episode of hepatitis A.

CASE

A 39-year-old previously healthy male presented to out-patient clinic with persistent jaundice and elevated liver enzymes. He had visited another hospital 4 weeks earlier due to a 1-week history of fatigue, nausea, and mild right upper quadrant abdominal pain. Initial laboratory tests revealed the following: aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 1,454 U/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 2,034 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 201 U/L, total bilirubin 3.7 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 2.8 mg/dL, and prothrombin time 12.8 seconds. Serologic testing for viral hepatitis showed positive HAV immunoglobulin M, while hepatitis B surface antigen, and anti-hepatitis C virus were negative. He was diagnosed with acute hepatitis A and was hospitalized for supportive care. After 3 weeks of admission, AST and ALT levels decreased to 101 U/L and 169 U/L, respectively. However, total bilirubin increased to 6.9 mg/dL, and the patient developed pruritus along with his previous symptoms. He reported no history of alcohol consumption, blood transfusion, or medication use.

On physical examination, he was icteric with mild abdominal tenderness, but there were no signs of chronic liver disease such as ascites or asterixis. Laboratory testing at our hospital revealed elevated AST (129 U/L) and ALT (184 U/L), total bilirubin (5.6 mg/dL), and markedly increased serum ferritin (2,299 ng/mL), and transferrin saturation (52.3%) (

Table 1). Autoimmune hepatitis markers were negative. Abdominal ultrasound showed hepatomegaly with stage F2 fibrosis (7.87 kPa on shear wave elastography) and no focal lesions.

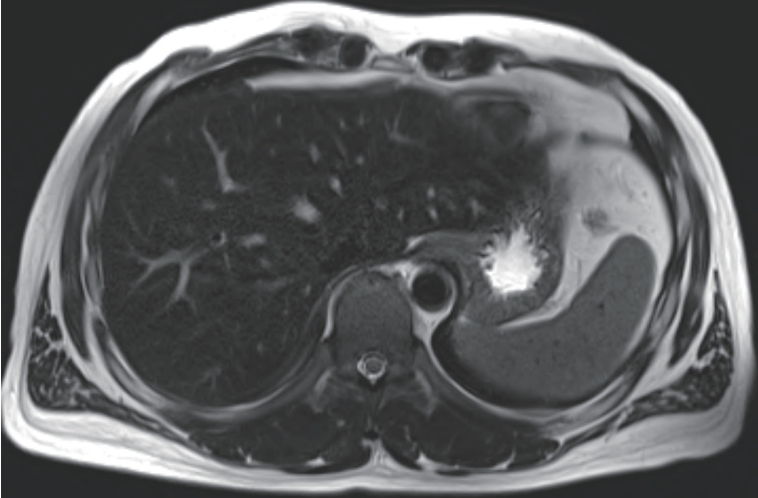

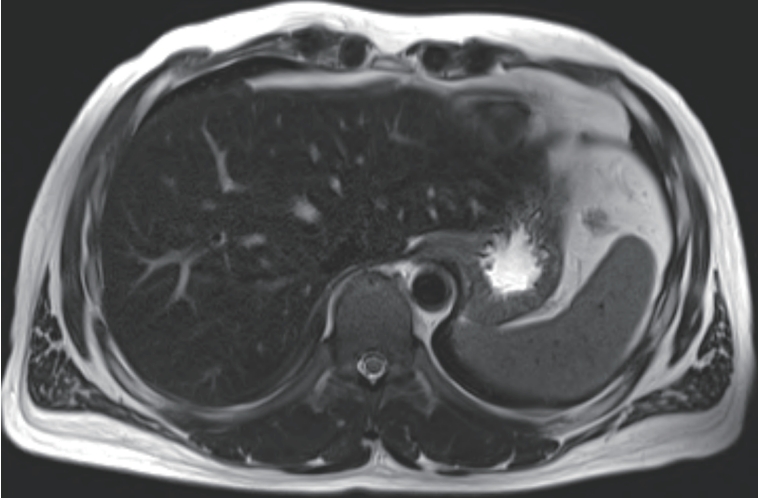

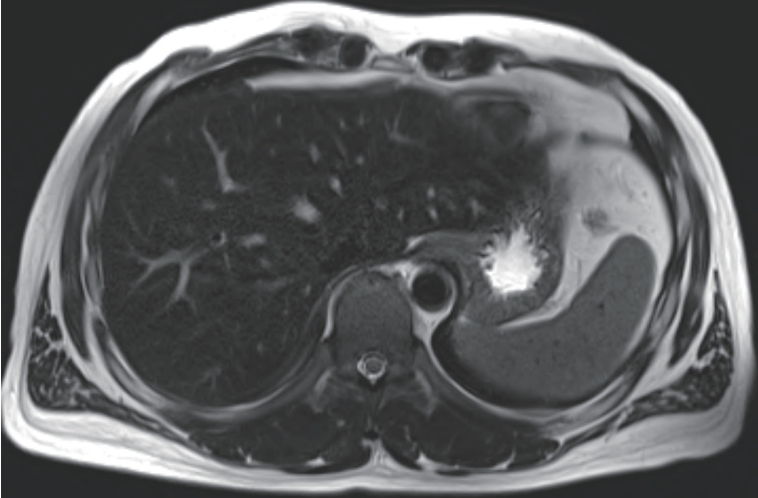

Given the improving liver function and elevated ferritin as a possible acute phase reactant, we initially considered that the patient was in the recovery phase of acute hepatitis A. Supportive treatment was continued, and serial laboratory follow-up was performed. Although total bilirubin levels gradually decreased during follow-up, AST and ALT levels rose again to 231 U/L and 409 U/L, respectively. Serum ferritin remained elevated (1,305 ng/mL), and transferrin saturation was also persistently high (53.4%). To evaluate hepatic iron deposition, liver MRI was performed. On T2-weighted imaging, the hepatic parenchyma showed relatively low signal intensity compared to the spleen, suggestive of iron accumulation (

Fig. 1).

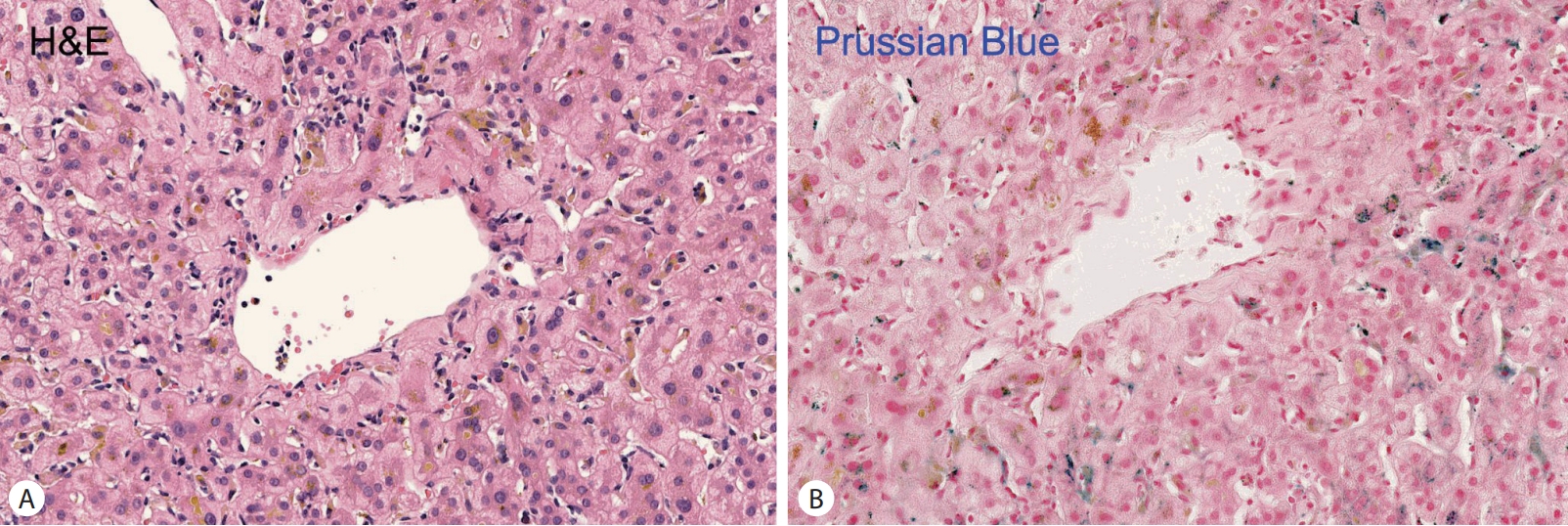

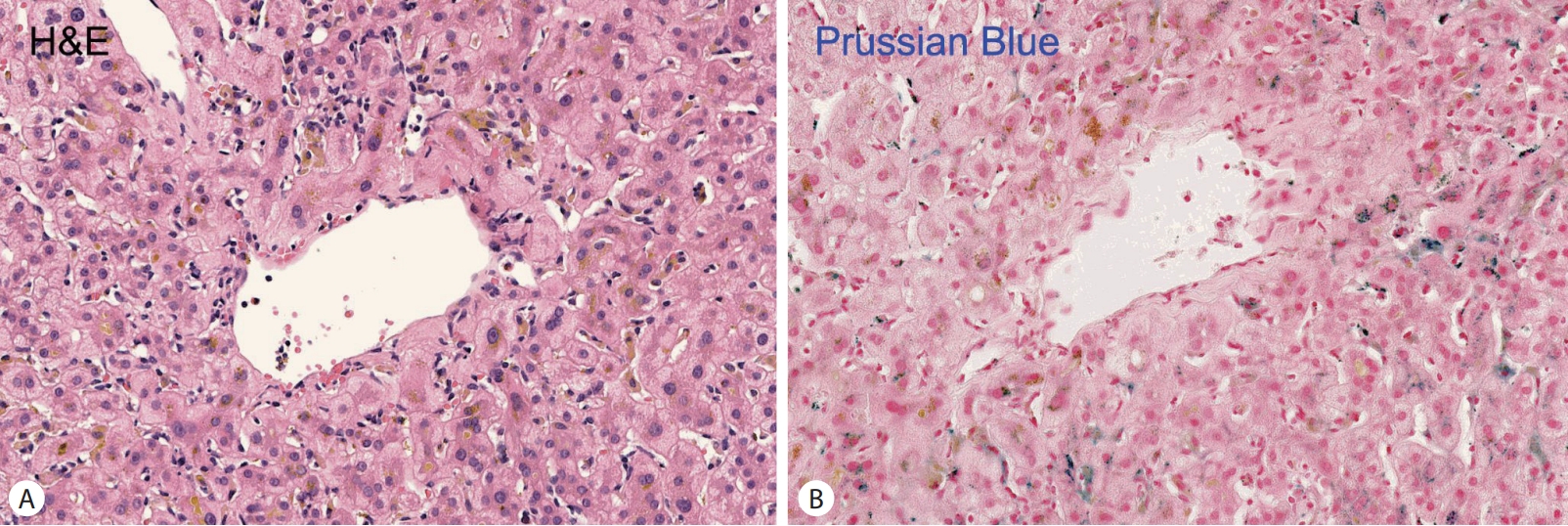

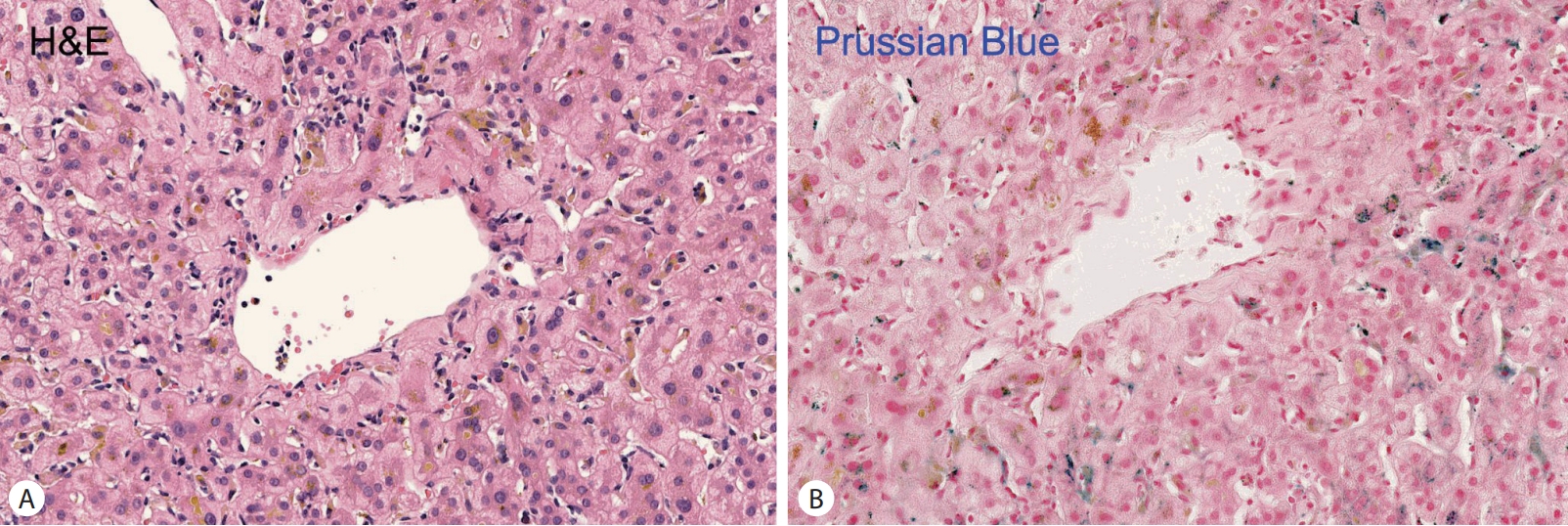

Based on the clinical, laboratory, and radiologic findings, hemochromatosis was suspected. A liver biopsy and

HFE gene analysis were conducted. Histologic examination revealed mild portal and lobular inflammation, periportal pigment deposition in hepatocytes, and positive Prussian blue staining indicative of iron overload (

Fig. 2).

HFE gene testing revealed no pathogenic mutations, and there was no family history of hemochromatosis. In the absence of other predisposing factors such as repeated blood transfusions, hemolytic disorders, excessive iron supplementation, alcoholic liver disease, or underlying chronic liver disease, a diagnosis of secondary hemochromatosis likely triggered by acute hepatitis A was made. Phlebotomy was initiated every 1–2 weeks. After 4 months of treatment, serum ferritin decreased to 52 ng/mL, and liver function tests normalized (

Table 1). The patient remained asymptomatic and continued to be followed in the outpatient clinic.

DISCUSSION

We report a rare case of secondary hemochromatosis developing after an acute episode of hepatitis A in a previously healthy adult. While iron overload is well-documented in chronic liver diseases such as chronic viral hepatitis or alcoholic liver disease [

4-

6], the occurrence of clinically significant iron accumulation following acute hepatitis A has not been previously reported to our knowledge.

Hepatitis A is typically a self-limiting illness with full recovery in immunocompetent adults. However, acute hepatic inflammation can temporarily disrupt iron homeostasis, leading to elevated serum ferritin as an acute-phase reactant. In our patient, initial hyperferritinemia was therefore attributed to the inflammatory response of acute hepatitis. However, the persistence of hyperferritinemia and high transferrin saturation beyond the resolution of liver inflammation prompted further investigation. Based on imaging findings, iron accumulation in the liver was suspected. Histologic evaluation confirmed hepatic iron deposition, and the absence of known genetic or secondary causes supported a diagnosis of secondary hemochromatosis, most likely induced by acute hepatitis A.

The mechanisms underlying secondary iron overload in this setting remain unclear. Acute liver injury may impair hepcidin synthesis, a key regulator of systemic iron homeostasis [

6]. Hepcidin is a liver-derived peptide hormone that maintains iron balance by binding to and inducing the degradation of ferroportin. Ferroportin, the only known cellular iron exporter, normally mediates dietary iron absorption from enterocytes and iron release from macrophages. A deficiency of hepcidin leads to upregulated ferroportin expression, resulting in excessive iron efflux into the circulation. Consequently, systemic iron overload may develop, with excess iron depositing in various organs, including the liver, heart, and pancreas. Additionally, hepatocyte injury may result in the release of intracellular iron into the circulation. These processes, although typically transient, may cause iron accumulation in predisposed individuals even in the absence of HFE mutations.

In this case, therapeutic phlebotomy was effective in reducing iron stores and normalizing liver function [

7]. The patient showed rapid clinical and biochemical improvement, highlighting the importance of early recognition and intervention. Although secondary hemochromatosis is generally associated with chronic iron loading conditions such as transfusion-dependent anemia or chronic hepatitis, this case emphasizes that acute liver insults, including HAV infection, may also precipitate significant iron overload in rare instances.

This case contributes to the expanding spectrum of conditions associated with acquired iron overload and suggests that clinicians should consider secondary hemochromatosis in patients with persistent hyperferritinemia and abnormal liver enzymes even after resolution of acute hepatitis. Further research is needed to better elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms and identify risk factors for iron dysregulation following acute hepatic injury.

NOTES

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Young-Il Yang, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6926-9759

-

FUND

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (No. 2020R1G1A1009088).

-

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (BPIRB 2025-06-033). The consent for publication was not required as the submission does not include any images or information that may identify the person.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.S.Y. designed the study. S.H.P., M.N.K., and Y-I.Y were responsible for the data acquisition; S.H.P. analyzed the data; S.H.P., M.N.K., Y-I.Y., and J.S.Y. wrote the first draft; Y-I.Y. and J.S.Y. critically reviewed the manuscript; J.S.Y. supervised the project; All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Figure 1.Liver Magnetic Resonance Imaging at the time of liver biopsy. On T2-weighted imaging, the hepatic parenchyma shows relatively low signal intensity compared to the spleen.

Figure 2.Histologic features of the liver tissue. Iron deposition appears as brown pigment within hepatocytes, Hematoxylin–eosin staining (400×) (A). Prussian blue staining highlights iron deposition in hepatocytes, visible as large dark blue granules (400×) (B).

Table 1.Changes in iron metabolism and liver function tests before and after therapeutic phlebotomy

Table 1.

|

Variables |

Baseline (other hospital) |

Week 4 (our hospital) |

Week 10 (liver biopsy) |

Week 14 (2 weeks post-TP) |

Week 18 (6 weeks post-TP) |

Week 28 (16 weeks post-TP) |

|

Serum Iron (μg/dL) |

|

181 |

179 |

76 |

81 |

81 |

|

Serum ferritin (ng/mL) |

|

2,299 |

1,305 |

614 |

161 |

52 |

|

TS (%) |

|

52.3 |

53.4 |

25 |

24.3 |

23.3 |

|

AST (U/L) |

1,454 |

129 |

231 |

27 |

21 |

27 |

|

ALT (U/L) |

2,034 |

184 |

409 |

55 |

28 |

33 |

|

TB (mg/dL) |

3.7 |

5.6 |

2.6 |

1.1 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

|

DB (mg/dL) |

2.8 |

4.3 |

1.7 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

REFERENCES

- 1. Van Damme P, Pintó RM, Feng Z, Cui F, Gentile A, Shouval D. Hepatitis A virus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2023;9:51.

- 2. Olynyk JK, Ramm GA. Hemochromatosis. N Engl J Med 2022;387:2159-2170.

- 3. Pak K, Ordway S, Sadowski B, Canevari M, Torres D. Wilson’s disease and iron overload: Pathophysiology and therapeutic implications. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken) 2021;17:61-66.

- 4. Ye Y, Xie J, Wang L, He C, Tan Y. Chronic hepatitis B complicated with secondary hemochromatosis was cured clinically: A case report. Open Med (Wars) 2023;18:20230693.

- 5. Chapman RW, Morgan MY, Laulicht M, Hoffbrand AV, Sherlock S. Hepatic iron stores and markers of iron overload in alcoholics and patients with idiopathic hemochromatosis. Dig Dis Sci 1982;27:909-916.

- 6. Hörl WH, Schmidt A. Low hepcidin triggers hepatic iron accumulation in patients with hepatitis C. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014;29:1141-1144.

- 7. Fitzsimons EJ, Cullis JO, Thomas DW, Tsochatzis E, Griffiths WJH; British Society for Haematology. Diagnosis and therapy of genetic haemochromatosis (review and 2017 update). Br J Haematol 2018;181:293-303.

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by