ABSTRACT

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, largely because of its late detection and high recurrence rates. Conventional biomarkers such as alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) are unable to detect early-stage diseases with sufficient accuracy. Exosomal microRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs, encapsulated within extracellular vesicles, that have emerged as highly sensitive and specific non-invasive biomarkers with revolutionary potentials for improving HCC diagnosis and prognosis prediction. Several studies have demonstrated that circulating exosomal miRNAs outperform AFP detection in differentiating early-stage HCC from chronic liver disease and in predicting metastasis, recurrence, and patient survival. Furthermore, multi-miRNA panels and AI-driven predictive models integrating exosomal miRNA signatures with clinical parameters enhance the diagnostic accuracy and enable personalized risk stratification. Despite promising results, clinical implementation has been challenged by assay standardization, interpatient variability, and the need for large-scale prospective validation. Future research should include developing robust, high-throughput exosomal miRNA detection platforms, incorporating machine learning for optimized biomarker selection, and integrating exosomal miRNAs with other liquid biopsy approaches for comprehensive disease monitoring. In summary, exosomal miRNAs represent a powerful tool for revolutionizing the early detection and tailored management of HCC, ultimately improving patient outcomes through timely and precise interventions.

-

KEYWORDS: Exosome; microRNA; Hepatocellular carcinoma; Diagnosis; Prognosis

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of primary liver cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide [

1]. Early detection is crucial for improving prognosis, as patients diagnosed at an early stage can benefit from potentially curative interventions, such as surgical resection, liver transplantation, or local ablation therapies. Despite established surveillance programs targeting high-risk populations, several cases are still diagnosed at intermediate or advanced stages, resulting in poor clinical outcomes and limited treatment options [

2]. Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is a widely used blood-based biomarker for HCC surveillance and diagnosis [

3]. However, AFP has certain limitations, including suboptimal sensitivity and specificity, particularly for detecting small- or early-stage tumors. Approximately 40% of patients with early-stage HCC present with normal AFP levels, whereas elevated AFP levels may be detected in benign liver diseases such as chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis [

4,

5]. These limitations underscore the requirement for more accurate and non-invasive biomarkers to improve early detection and enable timely therapeutic interventions.

Exosomes are nanosized extracellular vesicles (50–200 nm) that are actively secreted by almost all cell types into various biological fluids, including blood, urine, saliva, and ascitic fluid [

6,

7]. They originate from the endosomal compartment through the inward budding of multivesicular bodies that are then released into the circulation via exocytosis. Exosomes contain a complex molecular cargo, including proteins, lipids, DNA, mRNAs, and non-coding RNAs, which reflect the physiological or pathological state of their cells of origin [

8]. Exosomes play essential roles in intercellular communication and transport of bioactive molecules; hence, modulating tumor growth, immune responses, and metastasis mechanisms [

9-

11]. Furthermore, exosomes’ lipid bilayer confers protection to their molecular contents, allowing for stable transport and reliable detection in peripheral fluids, which makes them ideal as non-invasive diagnostic biomarkers [

7,

12]. Tumor-derived exosomes carry unique molecular signatures that can distinguish patients with early-stage HCC from those with benign liver conditions or healthy individuals [

13,

14]. For example, exosome-associated proteins, oncogenic signaling molecules, and nucleic acids have shown significant diagnostic potentials, often surpassing the sensitivity and specificity of traditional serum markers, such as AFP [

15-

18]. Furthermore, the abundance and molecular composition of exosomes in the circulation appear to correlate with tumor stage and aggressiveness, supporting their role not only in diagnosis but also in disease monitoring and prognosis [

19,

20].

Among the biomolecules carried by exosomes, microRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as promising diagnostic biomarkers. miRNAs are small non-coding RNA molecules (18–25 nucleotides) that post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression by binding to target mRNAs, leading to translational repression or degradation [

21,

22]. They act as key regulators of fundamental biological processes, including cell differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, metabolism, and immune modulation [

23-

28]. In HCC, dysregulated expression of oncogenic miRNAs (e.g., miR-21 and miR-221) and tumor-suppressive miRNAs (e.g., miR-122 and miR-199a) is consistently observed in tumor tissues and the circulation [

29-

31]. These specific expression profiles often surpass those of AFP in distinguishing HCC from benign liver diseases, especially in the early stages. Encapsulation within exosomes or binding to proteins protects miRNAs from enzymatic degradation, thus contributing to their remarkable stability in body fluids and enhancing their value as minimally invasive biomarkers.

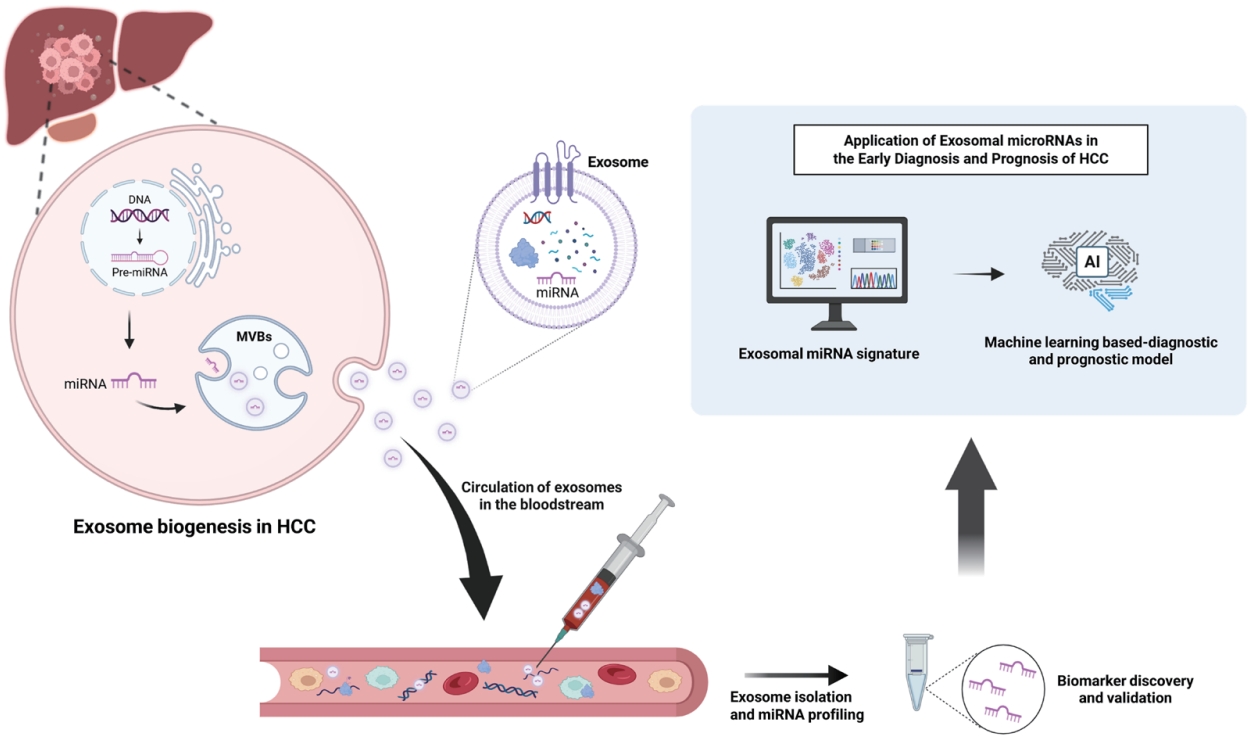

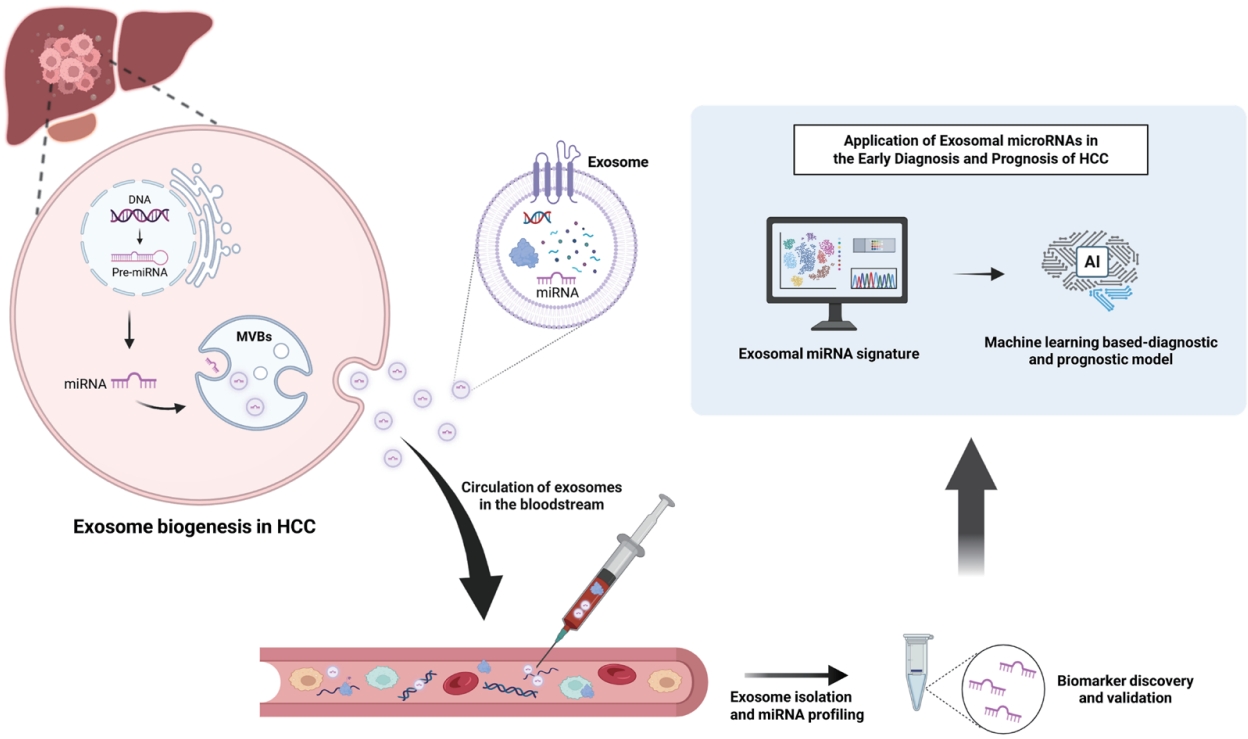

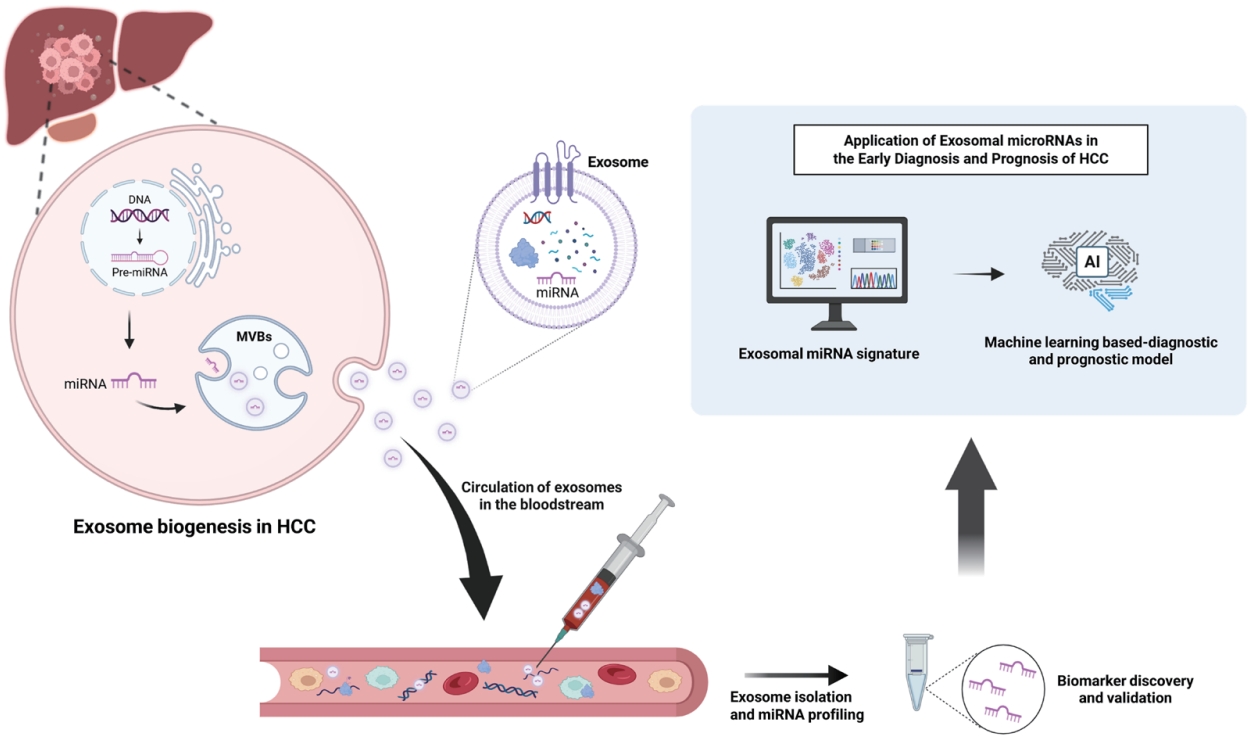

Exosomal miRNAs offer several diagnostic advantages over free-circulating miRNAs (

Fig. 1). The protective lipid bilayer improves stability, whereas tumor-specific enrichment enables the detection of early neoplastic changes, even with a low tumor burden [

32-

35]. Panels of exosomal miRNAs outperform AFP in differentiating early-stage HCC from chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis [

35,

36]. Integrating exosomal miRNA profiles with current imaging and serological approaches may help overcome the limitations of existing biomarkers, thus enabling prompt diagnosis, close monitoring, and improved patient outcomes.

EXOSOME FEATURES AND DIAGNOSTIC RELEVANCE

Exosomes are nanosized extracellular vesicles formed through a complex and highly regulated endosomal pathway. The process begins with invagination of the plasma membrane, generating early endosomes that subsequently mature into multivesicular bodies (MVBs) [

37]. Within MVBs, intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) are produced by inward budding of the endosomal membrane [

38]. Cargo, comprising proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, is selectively sorted into ILVs through the coordinated action of endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT-0, I, II, and III) and accessory proteins such as Alix and TSG101 [

39]. Vesicle formation is also mediated via ESCRT-independent mechanisms, including tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, and CD81) and ceramide-enriched lipid microdomains. MVBs have two possible fates: fusion with lysosomes for degradation or fusion with the plasma membrane to release ILVs as exosomes [

40]. This secretion is finely regulated by Rab GTPases (Rab27a/b, Rab11, and Rab35) and SNARE proteins to ensure precise vesicle trafficking and release [

41].

Exosomes contain selectively enriched bioactive molecules, such as proteins (tetraspanins, integrins, and heat shock proteins), nucleic acids (miRNAs, lncRNAs, mRNAs, and DNA fragments), and lipids, which mirror the physiological or pathological state of their cells of origin [

42,

43]. Their lipid bilayer protects the cargo from enzymatic degradation, thus allowing its stable circulation in biofluids such as blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid [

44]. Additionally, tumor-derived exosomes enclose oncogenic molecules that promote cancer progression, rendering them precise molecular fingerprints of the disease [

45,

46].

Accurate isolation and characterization of exosomes from serum are critical steps for their clinical application as diagnostic biomarkers. Multiple methods have been developed to isolate exosomes based on their physical and biochemical properties, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

1. Differential ultracentrifugation

Differential ultracentrifugation is the most commonly used and historically regarded as the “gold standard” for exosome isolation [

47]. This method involves sequential centrifugation steps to remove cells, cell debris, and larger vesicles, followed by high-speed ultracentrifugation (100,000 ×g) to pellet exosomes. Although widely used, it is time-consuming, requires specialized equipment, and may result in co-isolation of non-exosomal particles such as protein aggregates and lipoproteins [

48].

2. Density gradient ultracentrifugation

Density gradient ultracentrifugation, often using sucrose or iodixanol gradients, improves purity by separating exosomes based on their buoyant density (1.13–1.19 g/mL) [

49]. This method provides higher specificity compared to differential ultracentrifugation but is even more labor-intensive and has lower overall yield, making it less suitable for high-throughput clinical applications [

50].

3. Ultrafiltration

Ultrafiltration uses membrane filters with defined molecular weight cut-offs to concentrate and isolate exosomes based on size [

51]. This technique is faster than ultracentrifugation and does not require high-speed centrifuges; however, filter clogging and potential deformation of vesicles due to pressure can affect the recovery and integrity of exosomes [

52].

4. Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC)

Size-exclusion chromatography separates exosomes from serum based on their size as they pass through porous beads [

53]. SEC has been shown to effectively remove protein contaminants, providing high-purity exosome preparations suitable for downstream omics analyses. It is also gentle on vesicles, preserving their biological activity. However, the yield is typically lower than other methods, and multiple fractions must be collected and pooled [

54].

5. Polymer-based precipitation

Polymer-based precipitation methods use hydrophilic polymers such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) to reduce exosome solubility and promote their precipitation [

55]. These methods are simple, do not require specialized equipment, and are commercially available as kits for clinical use. Nonetheless, they have limited specificity and often co-precipitate other extracellular vesicles and non-vesicular proteins, potentially interfering with downstream analyses [

48].

6. Immunoaffinity capture

Immunoaffinity-based techniques employ antibodies targeting exosomal surface markers (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81) to selectively isolate exosomes from serum [

56]. This approach provides high specificity and enables the isolation of diseaseor cell type-specific exosome populations. However, it is costly, has limited scalability, and may not capture all exosome subtypes due to marker heterogeneity [

57].

7. Microfluidic technologies

Microfluidic-based isolation methods have emerged as innovative platforms for exosome enrichment, integrating immunoaffinity, filtration, or acoustic separation within lab-on-a-chip devices [

58]. These techniques allow rapid, small-volume processing with high sensitivity, making them attractive for point-of-care diagnostics. While promising, their adoption in clinical settings remains limited due to device complexity and standardization challenges [

59].

These biological characteristics form the basis of their diagnostic value. Disease-specific cargo enrichment enables the highly specific detection of pathological states, while exceptional stability ensures reproducible biomarker measurements from minimally processed samples. Furthermore, their nanoscale size and ability to cross biological barriers expand their diagnostic access to otherwise inaccessible tissues [

60-

62]. In HCC, circulating exosomes exhibit unique miRNA and protein signatures that help distinguish early-stage disease from chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis, often with greater sensitivity and specificity than that of AFP measurement. In addition, longitudinal profiling of exosomal cargo allows the dynamic monitoring of tumor progression and therapeutic response [

63]. In summary, the mechanisms underlying exosome biogenesis shape their molecular composition and establish their utility as robust and non-invasive biomarkers for HCC and other diseases.

EXOSOMAL MIRNAS AS DIAGNOSTIC MARKERS IN HCC

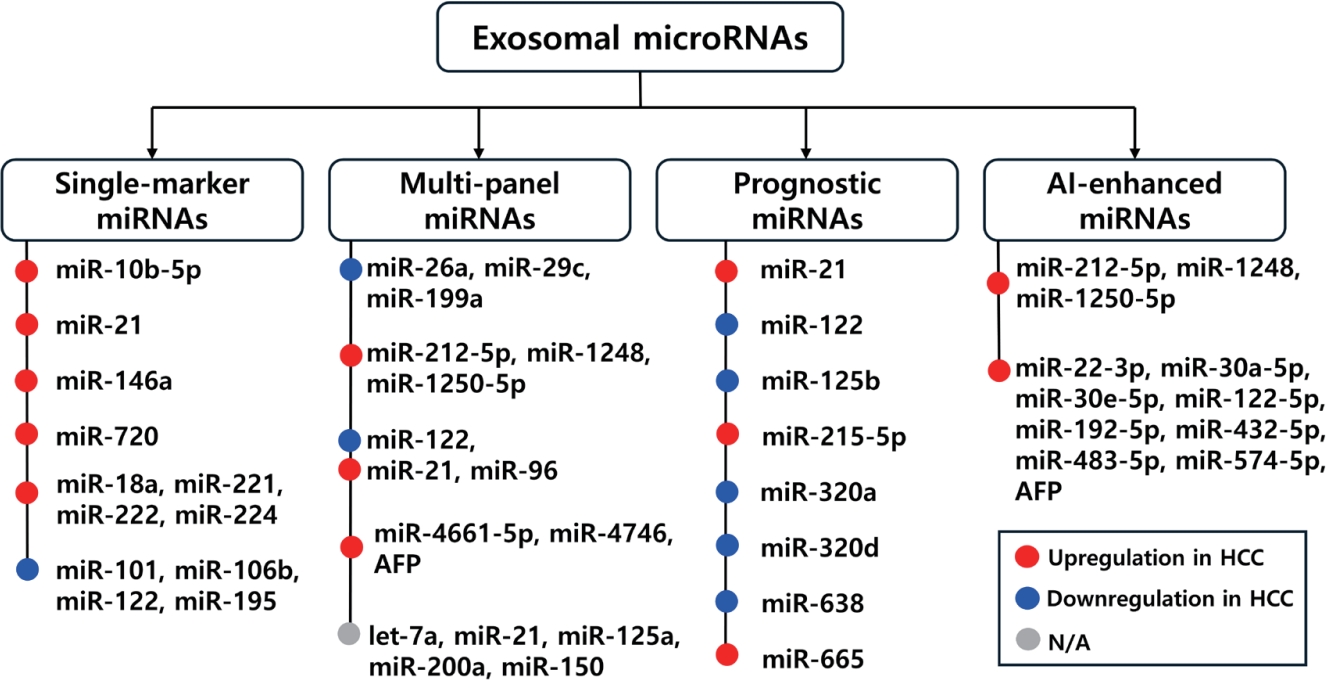

Exosomal Single miRNAs as a Diagnostic Biomarker in HCC

1. Exosomal miR‑10b‑5p

Validation studies confirmed that serum exosomal miR-10b-5p is a high-performing single marker for early HCC diagnosis. Using a 1.8-fold expression cutoff, an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.932 (sensitivity 91.1%, specificity 75.0%) was achieved for overall HCC detection, with similar accuracy for mUICC stage I/II (AUC=0.946) and stage I alone (AUC=0.934) [

64]. Exosomal miR-10b-5p significantly outperformed free serum miR-10b-5p (AUC=0.975 vs. 0.675), and the addition of AFP did not further improve the accuracy.

2. Exosomal miR‑21

Several studies have highlighted serum exosomal miR‑21 as a promising biomarker for early detection of HCC. Quantitative RT-PCR results showed that exosomal miR-21 levels were significantly higher in patients with HCC than those with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) and healthy controls (2.12-fold vs. CHB; 5.57-fold vs. controls; p<0.0001); in addition, they were significantly higher than whole serum miR-21 levels. Increased levels of miR-21 correlate with cirrhosis and tumor stage, indicating their clinical relevance [

65]. Similarly, plasma small extracellular vesicle (sEV)-derived miR-21-5p level was significantly increased in patients with HCC compared to those with liver cirrhosis (LC) (p=0.017) [

66].

3. Exosomal miR-146a

In a TaqMan-based qRT-PCR study of 84 patients with HCC, 50 patients with cirrhosis, and 20 healthy controls, exosomal miR-146a was significantly upregulated in HCC group compared to other groups (p=0.0001) [

67]. For distinguishing HCC from cirrhosis, ROC analysis generated an AUC of 0.80±0.14, with sensitivity 81±13% and specificity 58±22%.

4. Exosomal miR‑720

A Korean clinical study evaluated serum exosomal miR‑720 as a diagnostic biomarker for differentiating patients with HCC from non-HCC liver disease controls [

68]. Exosomal miR‑720 demonstrated excellent discriminative power, with an AUC of 0.931 (95% CI 0.881–0.981), sensitivity of 86.0%, and specificity of 82.4%, outperforming the traditional markers AFP and PIVKA‑II. The performance was strong even for small HCC lesions (<5 cm), where the AUC remained at 0.930 and the sensitivity and specificity remained high. Additionally, exosomal miR‑720 levels were not influenced by aminotransferase elevation, thus enhancing its applicability to inflamed liver conditions.

5. Exosomal miR-18a, miR-221, miR-222, miR-224

Sohn et al. compared serum-derived exosomal miRNA expression profile between patients with HBV-related chronic liver disease and those with HCC, assessing their potential as single diagnostic biomarkers [

69]. In HCC patients, exosomal miR-18a, miR-221, miR-222 and miR-224 were significantly upregulated compared with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) and liver cirrhosis (LC) groups (p<0.05), whereas miR-101, miR-106b, miR-122, and miR-195 were significantly downregulated compared with CHB (p=0.014, p<0.001, p<0.001, and p<0.001, respectively). Notably, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-224 remained significantly elevated, and miR-101 significantly reduced, in HCC versus LC comparisons. These findings indicate that individual exosomal miRNAs can provide clinically relevant information for early HCC detection and offer mechanistic insights into tumor biology.

Collectively, single exosomal miRNAs demonstrate strong diagnostic potential for early-stage HCC (

Table 1). They consistently outperformed serum-based miRNAs or protein markers, such as AFP, with higher sensitivity and specificity in small tumors and hepatic inflammation. These attributes support their integration into screening and surveillance protocols to enhance early detection and improve clinical outcomes.

1. Rationale for Multi-miRNA Panels

Although several single exosomal miRNAs show promise in HCC diagnosis, their performance can be affected by tumor heterogeneity, disease etiology (HBV, HCV, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease), disease stage, and concurrent liver inflammation. This variability may lead to false-positive or false-negative results in specific patient subgroups. Moreover, no single miRNA consistently achieves optimal sensitivity and specificity across all disease stages, particularly in differentiating early-stage tumors from benign liver diseases, such as cirrhosis. Multi-miRNA panels address these challenges by integrating complementary biomarkers (oncogenic and tumor-suppressive miRNAs with distinct expression patterns) thus covering a broader spectrum of tumor-associated molecular changes. This strategy enhances robustness against biological variability, improves discrimination between HCC and non-malignant liver conditions, and often outperforms conventional serum biomarkers, such as AFP.

2. Panel 1: miR-26a, miR-29c, miR-199a

A seminal study evaluated a three-miRNA panel (miR‑26a, miR‑29c, miR‑199a) isolated from serum exosomes in cohorts of patients with HCC, cirrhosis, and healthy individuals [

35]. Each miRNA was significantly downregulated in patients with HCC compared to controls. The exosomal panel achieved outstanding discriminative capability: AUC=0.994 (sensitivity 100%, specificity 96%) when distinguishing patients with HCC from healthy controls and AUC=0.965 (sensitivity 92% and specificity 90%) when comparing patients with HCC to those with cirrhosis. This performance substantially exceeded that of plasma miRNA and AFP measurements.

3. Panel 2: miR-212-5p, miR-1248, miR-1250-5p (miRAGe model)

Hu et al. identified this panel in HBV-related HCC using high-throughput sequencing, qRT-PCR, and random forest feature selection [

70]. Integrated with clinical parameters (sex and cirrhosis), the panel achieved an AUC of 0.8634 in the training cohort and 0.7833 in the validation cohort, demonstrating a diagnostic performance comparable to that of AFP. Importantly, combining the exosomal miRNA panel with AFP and sex (the miRAGe model) markedly improved the diagnostic accuracy, reaching an AUC of 0.9499, a sensitivity of 89.0%, and a specificity of 94.7% in the overall cohort. In AFP-negative patients, a group that is notoriously challenging to detect, the panel maintained a robust performance (AUC=0.8338, sensitivity 87.5%, specificity 75.5%), indicating its potential to complement or even surpass AFP levels in specific clinical contexts.

4. Panel 3: miR-122, miR-21, miR-96

A panel comprising miR‑122, miR‑21, and miR‑96 was validated in serum exosomes from patients with HCC compared to those with cirrhosis [

71]. Combined with multivariate logistic regression, this miRNA panel achieved an AUC of 0.924 (sensitivity 82%, specificity 92%) for differentiating HCC from cirrhosis groups and nearly perfect discrimination (AUC=0.996, sensitivity 96%, specificity 98%) compared to healthy controls. Additionally, this exosomal panel had prognostic significance; patients with elevated miR‑21 or miR‑96 had poorer outcomes while higher miR‑122 levels correlated with better survival.

5. Panel 4: miR-25-3p, miR-1269a, miR-4661-5p, miR-4746-5p

Cho et al. identified and validated a potent exosomal miRNA panel for early-stage HCC diagnosis through an integrative analysis of three RNA-seq datasets combined with serum exosomal miRNA expression profiling [

72]. Six oncogenic miRNAs were initially selected and four (miR-25-3p, miR-1269a, miR-4661-5p, and miR-4746-5p) showed strong diagnostic performance (AUC>0.8) in the test cohort. In the validation cohort, exosomal miR-4661-5p emerged as the most accurate single marker (AUC=0.923 for early-stage HCC), significantly outperforming AFP (AUC=0.541). A two-miRNA panel combining exosomal miR-4661-5p and miR-4746-5p achieved outstanding accuracy for early-stage HCC (AUC=0.947, sensitivity=81.8%, specificity=91.7%), even in high-risk populations with chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis (AUC=0.954). This panel consistently outperformed AFP in all diagnostic scenarios, highlighting its potential utility in HCC surveillance. Moreover, high expression of exosomal miR-4661-5p correlated with vascular invasion and poor disease-free survival, suggesting an additional prognostic value.

6. Panel 5: let-7a, miR-21, miR-125a, miR-200a, miR-150 (Fucosylated EVs)

A novel diagnostic strategy was introduced using fucosylated extracellular vesicles (fu‑EVs) isolated from the serum via a glycan‑based lectin capture method called GlyExo‑Capture [

73]. In a multi-center cohort comprising 88 patients with HCC and 179 non-HCC controls, next-generation sequencing identified a signature of five miRNAs (let-7a, miR-21, miR-125a, miR-200a, and miR-150) that were significantly dysregulated in HCC fu-EVs compared to those in controls. This panel exhibited high diagnostic accuracy: in the combined cohort (194 HCC + 412 controls), it achieved a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 92%, with the five-miRNA signature outperforming both AFP and des‑gamma‑carboxy prothrombin (DCP). In particular, the model demonstrated strong recall rates for early-stage HCC (85.7% for stage 0 and 90.8% for stage A), identifying 88.1% of AFP-negative HCC cases, thus underscoring its utility in detecting tumors undiagnosed by conventional biomarkers. Furthermore, combining the fu- EV miRNA signature with AFP increased diagnostic accuracy, with AUC approaching 0.96, indicating the additive benefits of integrating fu‑EV biomarkers with standard serological tests. These findings highlight the importance of glycan-selected (fucosylated) EV‑derived multi-miRNA panels as promising robust tumor-specific liquid biopsy tools for early HCC detection, including AFP-negative and early-stage cases.

Across multiple studies, exosomal multi-miRNA panels have consistently outperformed single biomarkers and AFP, particularly in early stage and AFP-negative HCC (

Table 2). By integrating multiple molecular signatures, these panels offer greater diagnostic robustness, prognostic insight, and potential applicability to diverse etiologies and patient populations. Their strong performance in both discovery and validation cohorts supports further large-scale prospective trials to facilitate clinical translation.

Exosomal miRNAs are emerging as diagnostic tools, and robust prognostic and therapeutic monitoring biomarkers for HCC. Their stability in the circulation and tumor-specific expression profiles enable a non-invasive longitudinal assessment of disease progression and treatment efficacy.

1. Exosomal miR-21

Tumor-derived exosomal miR‑21 levels were substantially elevated in patients with HCC compared with healthy controls [

20]. Importantly, high exosomal miR‑21 expression was significantly associated with poor overall and disease-free survival in a cohort of 85 patients with HCC. Kaplan–Meier curves stratified by miR‑21 expression confirmed that higher levels predicted worse outcomes. Exosomal miR‑21 promotes tumor progression by reprogramming hepatic stellate cells into cancer-associated fibroblasts and stimulating the PDK1/AKT pathway and angiogenesis via PTEN suppression.

2. Exosomal miR-122

In patients with cirrhosis undergoing transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), pretreatment serum exosomal miR‑122 levels inversely correlated with liver function impairment (elevated Child-Pugh scores and higher AST/ALT). Lower miR‑122 expression predicted poorer disease-specific survival in cirrhotic HCC patients (HR=2.72, 95% CI 1.04–8.02; p=0.042), indicating its prognostic relevance in this subgroup [

74].

3. Exosomal miR-125b

A clinical study demonstrated that lower serum exosomal miR‑125b levels significantly correlated with HCC features indicative of metastasis, including multiple tumors, microvascular invasion, and advanced TNM stage. Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed that patients with reduced exosomal miR‑125b had a shorter time to recurrence and overall survival. ROC analysis showed predictive AUCs of 0.739 for recurrence and 0.702 for survival [

75].

4. Exosomal miR-215-5p

Serum exosomal miR‑215‑5p expression was elevated in patients with HCC compared to patients with chronic liver disease, and higher levels correlated with the presence of vascular invasion, advanced tumor stage, and significantly poorer disease-free survival (DFS) (p=0.02), suggesting its utility in identifying patients at high risk of early recurrence post-treatment [

64].

5. Exosomal miR-320a

In a study of 104 HCC patients, 55 with chronic liver disease, and 50 healthy controls, serum exosomal miR-320a levels were significantly lower in patients with HCC [

76]. Reduced expression correlated with lymph node metastasis, vascular invasion, and advanced TNM stage. Low miR-320a levels predicted shorter overall survival (OS) in Kaplan–Meier analysis and were confirmed as an independent prognostic factor in multivariate models. Furthermore, miR-320a levels increased significantly one month after curative surgery, indicating its potential as a dynamic marker of treatment response.

6. Exosomal miR-320d

Low serum exosomal miR-320d expression was significantly associated with advanced tumor stage, lymph node metastasis, and poor differentiation in HCC [

77]. Patients with low exosomal miR‑320d showed markedly shorter OS and DFS, and multivariate analysis confirmed its independent prognostic value (HR=2.851, 95% CI 1.18–5.69; p=0.021). Functional assays demonstrated that miR‑320d inhibits proliferation and invasion by targeting BMI1, hence supporting its role as a tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker.

7. Exosomal miR-638

Shi et al. analyzed serum exosomal miR‑638 in a cohort of 126 patients with HCC and 21 healthy controls, demonstrating that miR‑638 levels were significantly lower in HCC cases, particularly in those with larger tumors, vascular invasion, and advanced TNM stages. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis revealed that patients with low exosomal miR‑638 expression had significantly poorer OS than those with high expression. Multivariate Cox regression confirmed that miR‑638 was an independent prognostic factor for OS [

78]. Additional validation from a 2019 meta-analysis of exosomal miRNAs across solid tumors supported these findings, showing that downregulation of exosomal miR‑638 was significantly associated with shorter OS (HR=2.25, 95% CI: 1.46–3.46) [

79].

8. Exosomal miR-665

Elevated serum exosomal miR-665 levels have been linked to larger tumor size, advanced TNM stage, and capsule invasion [

80]. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed that high miR-665 expression was significantly associated with shorter OS.

Multiple studies showed that specific exosomal miRNAs, both oncogenic (e.g., miR-665, miR-21, and miR-215-5p) and tumor-suppressive (e.g., miR-638, miR-320a/d, miR-122, and miR-125b), consistently correlated with key clinicopathological features and survival outcomes in HCC (

Table 3). Their expression patterns not only stratify patient prognosis, but can also serve as dynamic indicators of treatment response. These findings support their integration into clinical workflows for risk assessment, post-treatment monitoring, and potential guidance of adjuvant therapy decisions.

Exosomal miRNAs undergo dynamic changes during and after therapeutic interventions, making them promising real-time indicators of treatment efficacy and early tumor recurrence in HCC.

1. Liver transplantation

Serum exosomal miR-718 was significantly downregulated in liver transplant recipients with HCC who developed recurrence compared to that in non-recurrent cases. Low miR-718 expression correlated with larger tumors, microvascular invasion, and advanced TNM stage, and independently predicted poorer recurrence-free survival. Reduced miR-718 expression led to the upregulation of its target gene HOXB8, promoting tumor aggressiveness [

63].

2. TACE-treated HCC

In patients with HCC undergoing TACE, serum exosomal miR-122 levels were significantly decreased post-treatment (p=0.012), whereas those of miR-21 remained unchanged. Pre-TACE miR-122 levels correlated with AST and ALT levels, tumor diameter, and Child-Pugh score. In the LC subgroup (n=57), a low post/pre-TACE miR-122 ratio independently predicted poor disease-specific survival (HR=2.72, 95% CI 1.04–8.02; p=0.042). These findings suggest that dynamic changes in exosomal miR-122 levels reflect residual liver function and may serve as a prognostic biomarker of post-TACE outcomes [

60].

These studies highlight the utility of exosomal miRNAs as minimally invasive biomarkers for the post-treatment surveillance of HCC. By enabling the early identification of recurrence and assessment of therapeutic efficacy, they can support risk stratification and guide personalized follow-up strategies.

Exosomal miRNAs as Predictors of Metastasis in HCC

Exosomal miRNAs have emerged as potential biomarkers for predicting metastatic risk in HCC. In addition to serving as indicators, these miRNAs actively influence tumor invasiveness and pre-metastatic niche formation.

1. Exosomal miR‑125b: Metastasis suppressor and recurrence predictor

In a large cohort of 239 patients with HCC, serum exosomal miR-125b levels were significantly lower in patients with extrahepatic metastasis than in those without (p=0.030). Low miR-125b expression was associated with higher metastasis rates (p=0.025) and showed a consistent decline in eight of nine patients with serial samples before and after metastasis. Functionally, exosomal miR-125b suppressed migration, invasion, MMP-2/9/14 expression, and TGF-β1/SMAD2-mediated epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) in recipient HCC cells, supporting its role as a tumor-suppressive biomarker for predicting early metastatic spread [

81].

2. Exosomal miR‑1247‑3p: Mediator of pre‑metastatic niche formation

In a clinical cohort, serum exosomal miR-1247-3p levels were markedly elevated in HCC patients with lung metastasis (n=20) compared to those without (n=90) and healthy controls (n=25; p<0.001). High miR-1247-3p expression in tumor tissues correlated with increased AFP, cirrhosis, tumor thrombus, and distant metastasis, and predicted poorer OS (p=0.0351) and DFS (p=0.0001). These findings indicate that circulating exosomal miR-1247-3p is a strong, non-invasive biomarker of metastatic potential and adverse prognosis in HCC [

82].

3. Exosomal miRNA panel for lung metastasis prediction

Huang et al. profiled plasma exosomal miRNAs from HCC patients with and without lung metastasis and identified 32 differentially expressed miRNAs between the two groups [

83]. Among these, six (let-7e, miR-18a, miR-27a, miR-221, miR-20b, and miR-652) were consistently upregulated in both plasma exosomes and matched metastatic tissue samples. ROC analysis of an independent Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) dataset (GSE67140) revealed that miR-18a, miR-27a, and miR-20b achieved high diagnostic performance in distinguishing metastatic from non-metastatic HCC with AUCs of 0.7722, 0.8282, and 0.8661, respectively. A three-miRNA panel combining miR-18a, miR-20b, and miR-221 further improved the AUC to 0.9040, outperforming any single miRNA. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis demonstrated that high expression of all six miRNAs correlated with significantly poorer OS, and elevated miR-652 levels also predicted shorter DFS (HR=2.09, p<0.009). Bioinformatic analysis indicated that these metastasis-associated miRNAs potentially regulate key pathways linked to EMT, including TGF-β/SMAD, PTEN/PI3K-Akt, and STAT3 signaling.

In summary, specific exosomal miRNAs, such as miR-125b and miR-1247-3p, and multi-miRNA panels showed strong potential for predicting metastatic behavior in HCC. They reflect metastatic risk, and participate in mechanistic pathways driving invasion and pre-metastatic niche formation. Integrating these biomarkers into surveillance protocols would enable earlier detection of metastasis-prone diseases and tailoring of therapeutic strategies.

AI-Enhanced Diagnostic Models Utilizing Exosomal miRNAs in HCC

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have transformed the discovery of exosomal biomarkers of HCC. Unlike traditional methods, AI/ML can analyze high-dimensional molecular data, uncover complex multi-marker signatures, and integrate clinical parameters, thereby enhancing diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity. These approaches enable robust, non-invasive detection and personalized risk stratification across diverse patient populations.

1. Random Forest–Based HBV-HCC Classifier

In an HBV-related early-stage HCC cohort (n=108 patients with HCC, n=102 controls), Hu et al. used high-throughput sequencing and a random forest machine learning algorithm to identify three plasma exosomal miRNAs, miR-212-5p, miR-1248, and miR-1250-5p, which are all significantly downregulated in HCC [

70]. A logistic regression model combining these miRNAs with sex and cirrhosis status achieved AUC of 0.8634 for training and 0.7833 for validation. The diagnostic performance of miRNAs, integrated with AFP and sex in the miRAGe model, improved markedly, reaching an AUC of 0.9499. This model also performed well in AFP-negative patients (AUC=0.8338), demonstrating its potential for the early detection of non-invasive HBV-related HCC.

2. High-Dimensional RNA Profile Compression

Yap et al. applied a support vector machine (SVM) algorithm to exosomal RNA profiles from 112 patients with HCC and 118 healthy controls, and identified a nine-RNA signature (seven mRNAs and two circRNAs) with strong diagnostic performance [

84]. From 114,602 exosomal RNA transcripts, the model identified a 9-RNA signature associated with immune response, platelet activation, and cytoskeletal organization. This panel achieved AUC values of 0.79–0.88 in the unseen test set and an overall accuracy of about 85%, outperforming traditional single biomarkers. This study highlights that machine learning can effectively compress high-dimensional exosomal data into a reliable diagnostic tool for non-invasive HCC detection.

3. Deep Learning with SMOTE-Augmented Data

Hwang et al. developed a deep-learning-based model that integrated eight serum exosomal miRNA signatures (miR-22-3p, miR-30a-5p, miR-30e-5p, miR-122-5p, miR-192-5p, miR-432-5p, miR-483-5p, and miR-574-5p) with AFP levels [

85]. In the validation cohort (n=175), the multi-marker model achieved AUC>0.95 for differentiating HCC from healthy controls and >0.90 for distinguishing HCC from cirrhosis, surpassing AFP alone (AUC≤0.90). For early-stage HCC, the AUC exceeded 0.94, even in patients with hepatitis or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) as controls. Applying SMOTE data augmentation maintained high accuracy (AUC 0.96–0.97) in distinguishing HCC patients from healthy controls, confirming model robustness. This integrated AI–exosomal miRNA approach demonstrated superior diagnostic performance and potential for precise and non-invasive HCC detection.

4. Deep Learning Applied to Exosome Spectroscopy

Yang et al. developed ChatExosome, an AI diagnostic system that integrates a Feature Fusion Transformer (FFT) with a retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) framework for the exosomal Raman spectral classification of HCC. The FFT model, employing multichannel preprocessing and patch-based self-attention, achieved 94.1% accuracy in distinguishing patients with HCC from healthy controls, and 87.5% accuracy for AFP-negative HCC cases. Clinical validation of 165 plasma samples demonstrated robustness across tumor stages and AFP levels. The RAG-enhanced Large language model (LLM) interface enabled interpretable results and interactive clinical decision support, offering a scalable platform for non-invasive real-time HCC detection [

86].

5. Ensemble Learning on Exosome-Related Genes

In a study using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, 424 cases) and International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) cohorts, Zhu et al. applied univariate feature selection and a random forest (RF) machine learning algorithm to identify 13 exosome-related genes (ERGs) significantly associated with OS [

87]. An ERG-based risk score classified patients into high-and low-risk groups with a one-year OS AUC of 0.820 in TCGA. Integrating ERG scores with mitosis, PI3K–Akt, B cell, NK cell, and CD8⁺ T-cell pathway scores yielded an RF signature with superior prognostic accuracy (TCGA AUCs: 0.845 at one year, 0.811 at two years; ICGC AUCs: 0.733 at one year, 0.749 at three years). Experimental validation confirmed the upregulation of BSG and SFN in HCC tissues and their knockdown suppressed HCC cell proliferation, supporting the biological relevance of the RF model.

AI-driven analysis of exosomal biomarkers offers high diagnostic accuracy, robust performance in early and AFP-negative HCC, and allows integration with clinical data for personalized surveillance (

Table 4). These approaches have a strong potential to complement or surpass current diagnostic strategies, enhancing non-invasive precision medicine in HCC management.

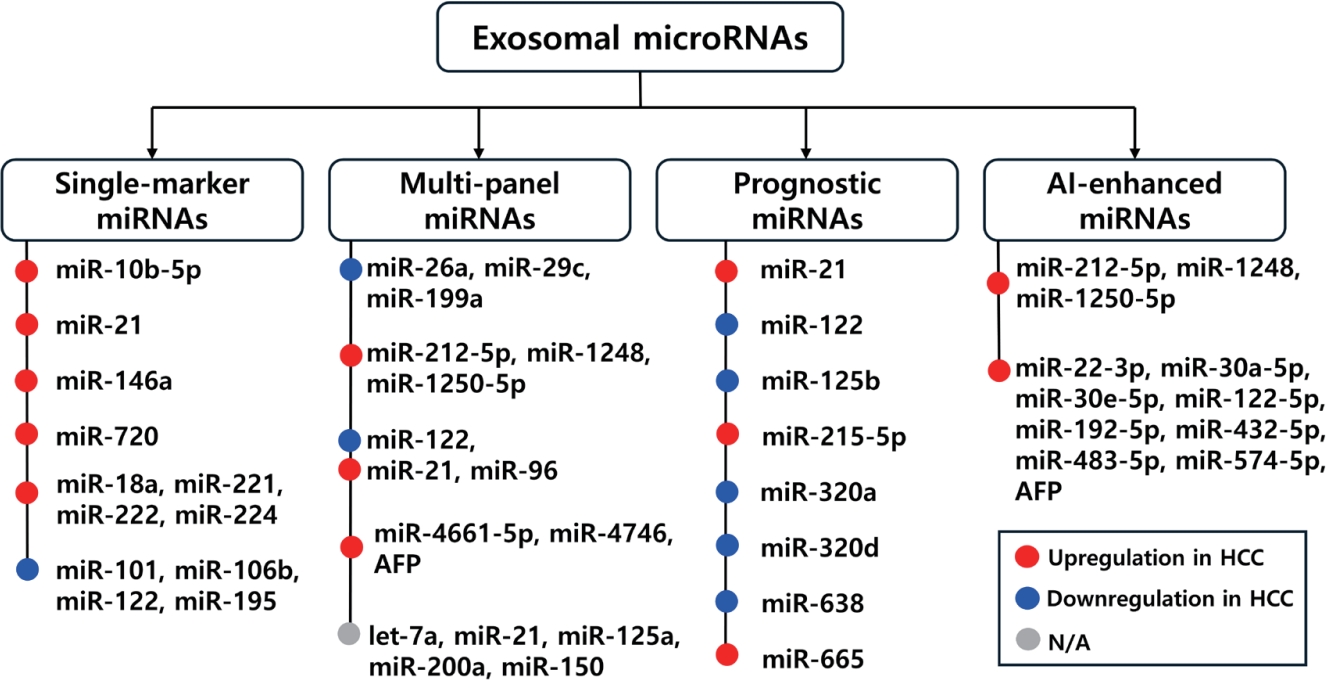

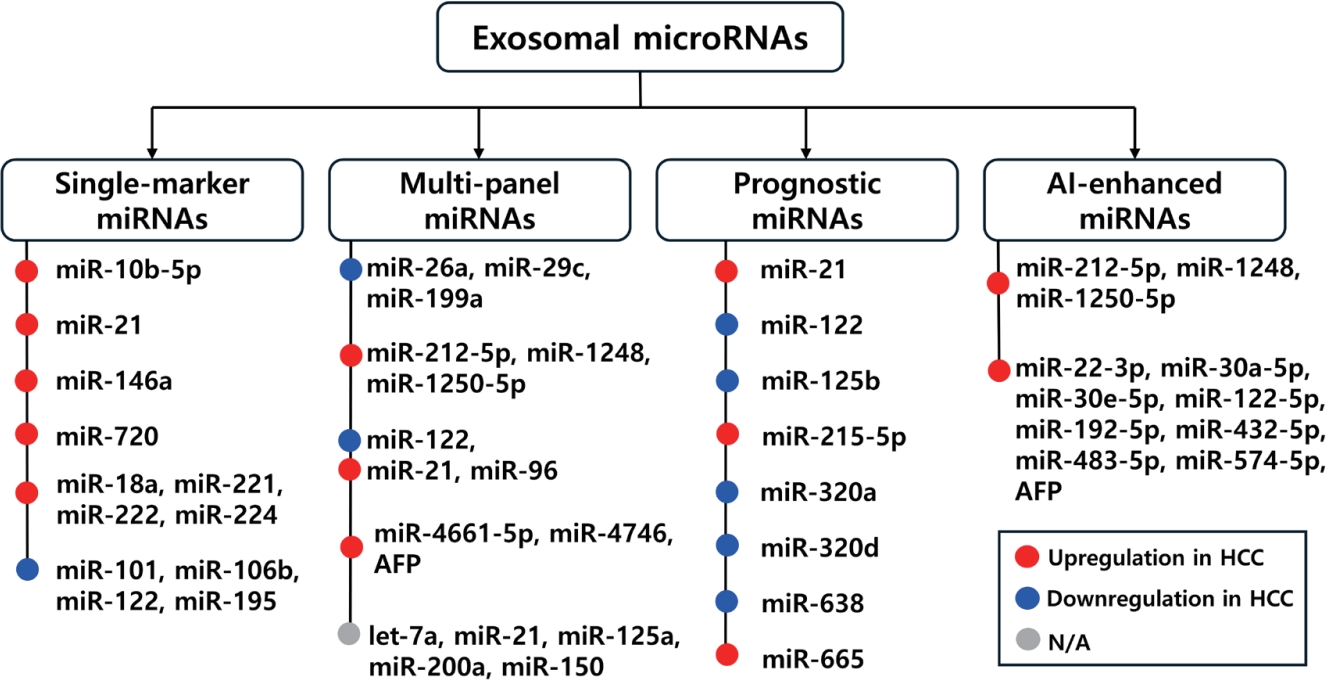

Exosomal miRNAs have emerged as promising non-invasive biomarkers for the early diagnosis, prognosis prediction, and therapeutic monitoring of HCC. Multiple studies have shown that tumor-derived exosomal miRNAs can accurately distinguish early-stage HCC from chronic liver diseases, predict metastatic potential, and correlate with survival outcomes, often outperforming conventional serum biomarkers, such as AFP (

Fig. 2). Their biological stability, selective enrichment, and ability to capture dynamic tumor-specific molecular signatures underscore their potential as precision medicine tools for HCC management.

However, several critical barriers must be addressed before routine clinical implementation becomes feasible. First, standardization across pre-analytical and analytical steps, including exosome isolation (e.g., ultracentrifugation vs. size-exclusion chromatography), RNA extraction, and miRNA quantification platforms (qRT-PCR, ddPCR, or NGS), is urgently required to reduce interlaboratory variability and enhance reproducibility. In addition, establishing internal reference controls and normalization strategies for exosomal miRNA analysis remains a key technical challenge. Second, biological heterogeneity, such as HCC etiology (e.g., HBV vs. NASH), tumor stage, and prior treatments can influence exosomal miRNA profiles. This highlights the need for large, ethnically and etiologically diverse multicenter validation cohorts to ensure broad applicability and robustness of diagnostic panels. Third, although several candidate miRNAs and multi-marker panels have shown promise, large-scale, prospective clinical trials are needed to evaluate their real-world performance, cost-effectiveness, and integration into existing HCC surveillance algorithms (e.g., with ultrasound and AFP).

To facilitate clinical translation, future research should prioritize several key directions. First, the development of high-throughput, automated, and point-of-care detection platforms, such as microfluidic chips and nanoplasmonic sensors, will be crucial for enabling rapid and accessible clinical testing of exosomal miRNAs. Second, there is a pressing need to establish universally accepted protocols for exosome isolation, RNA extraction, and data interpretation. These protocols should ideally be standardized through collaborative efforts by international consortia such as the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV), in order to reduce inter-laboratory variability and enhance reproducibility.

In addition, efforts should be made to integrate exosomal miRNA profiling with other diagnostic modalities, including circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), tumor-derived proteins, imaging- derived radiomics, and machine learning-based risk prediction models. Such multi-modal approaches may significantly improve diagnostic accuracy and enable more robust stratification of HCC risk. Finally, further mechanistic studies are needed to elucidate the functional roles of key exosomal miRNAs in driving HCC progression, immune evasion, and resistance to therapy. These insights will not only deepen our understanding of HCC biology but also support the development of novel therapeutic strategies targeting exosomal miRNAs.

In summary, exosomal miRNAs hold great promise as transformative tools for the early detection, individualized prognosis, and treatment guidance of HCC. With continued technological innovation and rigorous clinical validation, they may soon complement or even replace the current diagnostic approaches, ultimately improving patient outcomes through timely and precise interventions.

NOTES

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

-

FUND

This research was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning (RS-2025-00514590), the UST Young Scientist+ Research Program 2024 through the University of Science and Technology (No. 2024YS18, 2024YS20), and the KRIBB Research Initiative Program.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.K., N.G. and T-S.H. designed the study; S.K., N.G. and T-S.H. wrote the first draft of the manuscript and critically reviewed it; T-S.H. supervised the project; All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.Diagnostic and prognostic applications of exosomal miRNAs derived from the blood of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients. Exosomal miRNAs isolated from patient blood samples serve as promising biomarkers for non-invasive diagnosis, disease monitoring, and prognostic prediction in HCC. Recent advances in AI-driven models utilizing exosomal miRNA signatures further enhance diagnostic accuracy and support their potential for clinical application in early detection and personalized management of HCC. This figure was created with BioRender.com.

Figure 2.Schematic overview of exosomal miRNAs in HCC, categorized into single markers, multi-marker panel, prognostic markers, and AI-enhanced miRNA panels. The figure summarizes representative miRNA in each category, their diagnostic or prognostic performance, and clinical relevance for early detection, outcome prediction, and disease monitoring.

Table 1.Single exosomal miRNA as a diagnostic marker in HCC

Table 1.

|

Exosomal miRNA |

Exosome source |

miRNA detection platform |

Study cohort |

Diagnostic performance |

Reference |

|

miR-10b-5p |

Serum |

qRT-PCR |

HCC 90, CLD 60, healthy 28 |

AUC 0.934 (95% CI 0.874–0.971; mUICC I HCC vs. normal, CHB, LC) |

[64] |

|

miR-21 |

Serum |

qRT-PCR |

HCC 30, CHB 30, healthy 30 |

Upregulation in HCC |

[65] |

|

miR-21 |

Plasma |

qRT-PCR |

HCC 48, cirrhosis 38, healthy 20 |

Upregulation in HCC |

[66] |

|

miR-146a |

Plasma |

qRT-PCR |

HCC 85, cirrhosis 50, healthy 20 |

AUC 0.80 (HCC vs. cirrhosis) |

[67] |

|

miR-720 |

Serum |

qRT-PCR |

HCC 114, CLD 30 |

AUC 0.931 (95% CI 0.881–0.981; all HCC vs. CLD) |

[68] |

|

AUC 0.930 (95% CI 0.868–0.992; small HCC, <5 cm) |

|

miR-18a, miR-221, miR-222, miR-224 |

Serum |

qRT-PCR |

HCC 20, CHB 20, LC 20 |

Upregulated in HCC vs. CHB or LC (p<0.05) |

[69] |

|

miR-101, miR-106b, miR-122, miR-195 |

Serum |

qRT-PCR |

HCC 20, CHB 20, LC 20 |

Downregulated in HCC vs. CHB or LC (p≤0.014) |

[69] |

Table 2.Exosomal multi-miRNA panels in HCC diagnosis

Table 2.

|

Exosomal miRNA panel |

Exosome source |

miRNA detection |

Study cohort |

Diagnostic performance |

Reference |

|

miR-26a, miR-29c, miR-199a |

Serum |

qRT-PCR |

HCC 50, cirrhosis 50, healthy 50 |

AUC 0.994 (HCC vs. healthy) |

[35] |

|

AUC 0.965 (HCC vs. cirrhosis) |

|

miR-212-5p,miR-1248, miR-1250-5p (panel, “miRAGe”) |

Plasma |

qRT-PCR |

Early HBV-HCC 108, HBV non-HCC 102 |

AUC 0.8634 (95% CI 0.8027–0.9241; panel+sex, cirrhosis), AUC 0.9499 (95% CI 0.9192–0.9806; miRAGe: panel+AFP+sex) |

[70] |

|

miR-122, miR-21, miR-96 |

Plasma |

qRT-PCR |

HCC 50, cirrhosis 50, healthy 50 |

AUC 0.924 (HCC vs. cirrhosis) |

[71] |

|

AUC 0.996 (HCC vs. healthy) |

|

miR-4661-5p, miR-4746-5p, AFP |

Serum |

qRT-PCR |

Screening cohort (n=86) |

AUC 0.947 (95% CI 0.889–0.980; panel: miR-4661-5p+miR-4746-5p; early HCC vs. non-tumor) |

[72] |

|

Test cohort (n=24) |

AUC 0.925 (95% CI 0.861–0.966; panel: miR-4661-5p+AFP; early HCC vs. non-tumor) |

|

Validation cohort (n=144) |

|

let-7a, miR-21, miR-125a, miR-200a, miR-150 |

Serum |

qRT-PCR |

Combined cohort: HCC 194, non-HCC 412 |

Recall rate: 85.7% (stage 0), 90.8% (Stage A) |

[73] |

|

miRNA panel+AFP (AUC 0.96) |

Table 3.Exosomal miRNAs for prognosis in HCC

Table 3.

|

miRNA |

Exosome source |

Expression change |

Study cohort |

Diagnostic performance |

Reference |

|

miR-21 |

Serum |

↑ in HCC vs healthy |

HCC 85, healthy 10 |

- |

[20] |

|

miR-122 |

Serum |

↓ in HCC |

LC 57, CH 18 (TACE-treated cirrhotics 75) |

HR= 2.72 for poor DSS |

[74] |

|

miR-125b |

Serum |

↓ in HCC |

Cohort 1: CHB 30, LC 30, HCC 30 |

Recurrence (AUC=0.739), Survival (AUC=0.702) |

[75] |

|

Cohort 2: HCC 128 |

|

miR-215-5p |

Serum |

↑ in HCC vs controls |

HCC 90, CLD 60, healthy 28 |

- |

[64] |

|

miR-320a |

Serum |

↓ in HCC |

HCC 104, CLD 55, healthy 50 |

- |

[76] |

|

miR-320d |

Serum |

↓ in HCC |

HCC 110, healthy 40 |

AUC 0.869 (HCC vs. healthy) |

[77] |

|

HR=2.851 |

|

miR-638 |

Serum |

↓ in HCC |

HCC 126, healthy 21 |

- |

[78] |

|

A meta-analysis |

HR=2.25 |

[79] |

|

miR-665 |

Serum |

↑ in HCC |

HCC 30, healthy 10 |

- |

[80] |

Table 4.AI-Enhanced diagnostic models utilizing exosomal miRNAs in HCC

Table 4.

|

Exosomal miRNA (s) |

Model/Approach |

Diagnostic performance |

Reference |

|

miR-212-5p, miR-1248, miR-1250-5p, AFP |

RF for candidate selection+logistic regression (miRAGe panel integrating AFP, sex) |

AUC 0.9499 |

[70] |

|

9 exosomal RNAs (7 mRNAs, 2 circRNAs) |

SVM-based classification model using serum exosomal RNA |

AUC 0.79–0.88, Accuracy of ~85% |

[84] |

|

miR-22-3p, miR-30a-5p, miR-30e-5p, miR-122-5p, miR-192-5p, miR-432-5p, miR-483-5p, miR-574-5p, AFP |

Deep learning, SMOTE |

AUC >0.95 (HCC vs. healthy) |

[85] |

|

Not specified (Raman spectral features of plasma exosomes) |

FFT deep learning+LLM-based ChatExosome system |

Accuracy 94.1% |

[86] |

|

13 exosome-related genes (ERG) |

Univariate feature selection & RF machine learning algorithm |

Risk score: 1-year OS AUC=0.820 (high- and low-risk group) |

[87] |

REFERENCES

- 1. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024;74:229-263.

- 2. Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2018;391:1301-1314.

- 3. Wei Z, Zhang Y, Lu H, Ying J, Zhao H, Cai J. Serum alpha-fetoprotein as a predictive biomarker for tissue alpha-fetoprotein status and prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Transl Cancer Res 2022;11:669-677.

- 4. Kim DY, Toan BN, Tan CK, et al. Utility of combining PIVKA-II and AFP in the surveillance and monitoring of hepatocellular carcinoma in the Asia-Pacific region. Clin Mol Hepatol 2023;29:277-292.

- 5. Ma L, Guo H, Zhao Y, et al. Liquid biopsy in cancer: current status, challenges and future prospects. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024;9:336.

- 6. Kalluri R, LeBleu VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020;367:eaau6977.

- 7. Ghosh S, Rajendran RL, Mahajan AA, et al. Harnessing exosomes as cancer biomarkers in clinical oncology. Cancer Cell Int 2024;24:278.

- 8. Liu J, Ren L, Li S, et al. The biology, function, and applications of exosomes in cancer. Acta Pharm Sin B 2021;11:2783-2797.

- 9. Kalluri R. The biology and function of exosomes in cancer. J Clin Invest 2016;126:1208-1215.

- 10. Paskeh MDA, Entezari M, Mirzaei S, et al. Emerging role of exosomes in cancer progression and tumor microenvironment remodeling. J Hematol Oncol 2022;15:83.

- 11. Lin Zhang, Dihua Yu. Exosomes in cancer development, metastasis, and immunity. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2019;1871:455-468.

- 12. Donoso-Quezada J, Ayala-Mar S, González-Valdez J. The role of lipids in exosome biology and intercellular communication: Function, analytics and applications. Traffic 2021;22:204-220.

- 13. Sarkar S, Bishoyi AK, Roopashree R, et al. Exosomes in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Comprehensive Review of Current Research and Future Directions. J Cell Mol Med 2025;29:e70723.

- 14. Zhang Y, Zhang C, Wu N, et al. The role of exosomes in liver cancer: comprehensive insights from biological function to therapeutic applications. Front Immunol 2024;15:1473030.

- 15. Zhao L, Shi J, Chang L, et al. Serum-Derived Exosomal Proteins as Potential Candidate Biomarkers for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. ACS Omega 2021;6:827-835.

- 16. Yan R, Chen H, Selaru FM. Extracellular vesicles in hepatocellular carcinoma: Progress and challenges in the translation from the laboratory to clinic. Medicina 2023;59:1599.

- 17. Wang X, Liu Y, Jiang Y, Li Q. Tumor-derived exosomes as promising tools for cancer diagnosis and therapy. Front Pharmacol 2025;16:1596217.

- 18. Zeng Y, Hu S, Luo Y, He K. Exosome Cargos as Biomarkers for Diagnosis and Prognosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Pharmaceutics 2023;15:2365.

- 19. Zhang X, Yuan X, Shi H, et al. Exosomes in cancer: small particle, big player. J Hematol Oncol 2015;8:83.

- 20. Zhou Y, Ren H, Dai B, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma-derived exosomal miRNA-21 contributes to tumor progression by converting hepatocyte stellate cells to cancer-associated fibroblasts. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2018;37:324.

- 21. Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004;116:281-297.

- 22. Ha M, Kim VN. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014;15:509-524.

- 23. Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer 2006;6:857-866.

- 24. Abdul Manap AS, Wisham AA, Wong FW, et al. Mapping the function of MicroRNAs as a critical regulator of tumor-immune cell communication in breast cancer and potential treatment strategies. Front Cell Dev Biol 2024;12:1390704.

- 25. Han TS, Hur K, Xu G, et al. MicroRNA-29c mediates initiation of gastric carcinogenesis by directly targeting ITGB1. Gut 2015;64:203-214.

- 26. Han TS, Voon DC, Oshima H, et al. Interleukin 1 Up-regulates MicroRNA 135b to Promote Inflammation-Associated Gastric Carcinogenesis in Mice. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1140-1155.

- 27. Martino MTD, Tagliaferri P, Tassone P. MicroRNA in cancer therapy: breakthroughs and challenges in early clinical applications. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2025;44:126.

- 28. Khameneh SC, Razi S, Lashanizadegan R, et al. MicroRNA-mediated metabolic regulation of immune cells in cancer: an updated review. Front Immunol 2024;15:1424909.

- 29. Morishita A, Oura K, Tadokoro T, Fujita K, Tani J, Masaki T. MicroRNAs in the Pathogenesis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Review. Cancers Basel 2021;13:514.

- 30. Metcalf GAD. MicroRNAs: circulating biomarkers for the early detection of imperceptible cancers via biosensor and machine-learning advances. Oncogene 2024;43:2135-2142.

- 31. Tavakoli Pirzaman A, Alishah A, Babajani B, et al. The Role of microRNAs in Hepatocellular Cancer: A Narrative Review Focused on Tumor Microenvironment and Drug Resistance. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2024;23:15330338241239188.

- 32. Ljungström M, Oltra E. Methods for extracellular vesicle isolation: relevance for encapsulated miRNAs in disease diagnosis and treatment. Genes 2025;16:330.

- 33. Zhu M, Gao Y, Zhu K, Yuan Y, Bai H, Meng L. Exosomal miRNA as biomarker in cancer diagnosis and prognosis: A review. Medicine Baltimore 2024;103:e40082.

- 34. Xu D, Di K, Fan B, et al. MicroRNAs in extracellular vesicles: sorting mechanisms, diagnostic value, isolation, and detection technology. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022;10:948959.

- 35. Yang J, Dong W, Zhang H, et al. Exosomal microRNA panel as a diagnostic biomarker in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022;10:927251.

- 36. Yoo JS, Kang MK. Clinical significance of exosomal noncoding RNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma: a narrative review. J Yeungnam Med Sci 2025;42:4.

- 37. Colombo M, Raposo G, Thery C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2014;30:255-289.

- 38. Li J, Wang J, Chen Z. Emerging role of exosomes in cancer therapy: progress and challenges. Mol Cancer 2025;24:13.

- 39. Lee YJ, Shin KJ, Chae YC. Regulation of cargo selection in exosome biogenesis and its biomedical applications in cancer. Exp Mol Med 2024;56:877-889.

- 40. Wang W, Qiao S, Kong X, Zhang G, Cai Z. The role of exosomes in immunopathology and potential therapeutic implications. Cell Mol Immunol 2025;22:975-995.

- 41. Komori T, Fukuda M. Two roads diverged in a cell: insights from differential exosome regulation in polarized cells. Front Cell Dev Biol 2024;12:1451988.

- 42. Hanelova K, Raudenska M, Masarik M, Balvan J. Protein cargo in extracellular vesicles as the key mediator in the progression of cancer. Cell Commun Signal 2024;22:25.

- 43. Dixson AC, Dawson TR, Di Vizio D, Weaver AM. Context-specific regulation of extracellular vesicle biogenesis and cargo selection. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2023;24:454-476.

- 44. Yu J, Sane S, Kim JE, et al. Biogenesis and delivery of extracellular vesicles: harnessing the power of EVs for diagnostics and therapeutics. Front Mol Biosci 2023;10:1330400.

- 45. Lee J, Kim G, Han TS, et al. Positive regulation of cell proliferation by the miR-1290-EHHADH axis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Commun (Lond) 2024;44:705-709.

- 46. Zhang C, Qin C, Dewanjee S, et al. Tumor-derived small extracellular vesicles in cancer invasion and metastasis: molecular mechanisms, and clinical significance. Mol Cancer 2024;23:18.

- 47. Thery C, Amigorena S, Raposo G, Clayton A. Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr Protoc Cell Biol 2006;Chapter 3:Unit 3.22.

- 48. Linares R, Tan S, Gounou C, Arraud N, Brisson AR. High-speed centrifugation induces aggregation of extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles 2015;4:29509.

- 49. Cantin R, Diou J, Belanger D, Tremblay AM, Gilbert C. Discrimination between exosomes and HIV-1: purification of both vesicles from cell-free supernatants. J Immunol Methods 2008;338:21-30.

- 50. Li P, Kaslan M, Lee SH, Yao J, Gao Z. Progress in exosome isolation techniques. Theranostics 2017;7:789-804.

- 51. Cheruvanky A, Zhou H, Pisitkun T, et al. Rapid isolation of urinary exosomal biomarkers using a nanomembrane ultrafiltration concentrator. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2007;292:F1657-1661.

- 52. Zarovni N, Corrado A, Guazzi P, et al. Integrated isolation and quantitative analysis of exosome shuttled proteins and nucleic acids using immunocapture approaches. Methods 2015;87:46-58.

- 53. Boing AN, van der Pol E, Grootemaat AE, et al. Single-step isolation of extracellular vesicles by size-exclusion chromatography. J Extracell Vesicles 2014;3:3.

- 54. Baranyai T, Herczeg K, Onodi Z, et al. Isolation of exosomes from blood plasma: qualitative and quantitative comparison of ultracentrifugation and size exclusion chromatography methods. PLoS One 2015;10:e0145686.

- 55. Jiao R, Sun S, Gao X, et al. A Polyethylene glycol-based method for enrichment of extracellular vesicles from culture supernatant of human ovarian cancer cell line A2780 and body fluids of high-grade serous carcinoma patients. Cancer Manag Res 2020;12:6291-6301.

- 56. Tauro BJ, Greening DW, Mathias RA, et al. Comparison of ultracentrifugation, density gradient separation, and immunoaffinity capture methods for isolating human colon cancer cell line LIM1863-derived exosomes. Methods 2012;56:293-304.

- 57. Konoshenko MY, Lekchnov EA, Vlassov AV, Laktionov PP. Isolation of Extracellular Vesicles: General Methodologies and Latest Trends. Biomed Res Int 2018;2018:8545347.

- 58. Contreras-Naranjo JC, Wu HJ, Ugaz VM. Microfluidics for exosome isolation and analysis: enabling liquid biopsy for personalized medicine. Lab Chip 2017;17:3558-3577.

- 59. Shao H, Chung J, Balaj L, et al. Protein typing of circulating microvesicles allows real-time monitoring of glioblastoma therapy. Nat Med 2012;18:1835-1840.

- 60. Chen CC, Liu L, Ma F, et al. Elucidation of exosome migration across the blood-brain barrier model in vitro. Cell Mol Bioeng 2016;9:509-529.

- 61. Chen YF, Luh F, Ho YS, Yen Y. Exosomes: a review of biologic function, diagnostic and targeted therapy applications, and clinical trials. J Biomed Sci 2024;31:67.

- 62. Mohseni A, Salehi F, Rostami S, et al. Harnessing the power of exosomes for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of hematological malignancies. Stem Cell Res Ther 2025;16:6.

- 63. Sugimachi K, Matsumura T, Hirata H, et al. Identification of a bona fide microRNA biomarker in serum exosomes that predicts hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation. Br J Cancer 2015;112:532-538.

- 64. Cho HJ, Eun JW, Baek GO, et al. Serum exosomal microRNA, miR-10b-5p, as a potential diagnostic biomarker for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Med 2020;9:5.

- 65. Wang H, Hou L, Li A, Duan Y, Gao H, Song X. Expression of serum exosomal microRNA-21 in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed Res Int 2014;2014:864894.

- 66. Sorop A, Iacob R, Iacob S, et al. Plasma small extracellular vesicles derived miR-21-5p and miR-92a-3p as potential biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma screening. Front Genet 2020;11:712.

- 67. Frundt T, Krause L, Hussey E, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of miR-16, miR-146a, miR-192 and miR-221 in exosomes of hepatocellular carcinoma and liver cirrhosis patients. Cancers Basel 2021;13:10.

- 68. Jang JW, Kim JM, Kim HS, et al. Diagnostic performance of serum exosomal miRNA-720 in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Liver Cancer 2022;22:30-39.

- 69. Sohn W, Kim J, Kang SH, et al. Serum exosomal microRNAs as novel biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. Exp Mol Med 2015;47:e184.

- 70. Hu X, Huang F, Yao J, et al. Cross-sectional study on the diagnostic significance of plasma exosomal miRNAs in HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Transl Med 2024;22:1006.

- 71. Wang S, Yang Y, Sun L, Qiao G, Song Y, Liu B. Exosomal microRNAs as liquid biopsy biomarkers in hepatocellular carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther 2020;13:2021-2030.

- 72. Cho HJ, Baek GO, Seo CW, et al. Exosomal microRNA-4661-5p-based serum panel as a potential diagnostic biomarker for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Med 2020;9:5459-5472.

- 73. Li B, Hao K, Li M, et al. Five miRNAs identified in fucosylated extracellular vesicles as non-invasive diagnostic signatures for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Rep Med 2024;5:101716.

- 74. Suehiro T, Miyaaki H, Kanda Y, et al. Serum exosomal microRNA-122 and microRNA-21 as predictive biomarkers in transarterial chemoembolization- treated hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Oncol Lett 2018;16:3267-3273.

- 75. Liu W, Hu J, Zhou K, et al. Serum exosomal miR-125b is a novel prognostic marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther 2017;10:3843-3851.

- 76. Hao X, Xin R, Dong W. Decreased serum exosomal miR-320a expression is an unfavorable prognostic factor in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Int Med Res 2020;48:300060519896144.

- 77. Li W, Ding X, Wang S, et al. Downregulation of serum exosomal miR-320d predicts poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Lab Anal 2020;34:e23239.

- 78. Shi M, Jiang Y, Yang L, Yan S, Wang YG, Lu XJ. Decreased levels of serum exosomal miR-638 predict poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cell Biochem 2018;119:4711-4716.

- 79. Zhou J, Guo H, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Liu H. A meta-analysis on the prognosis of exosomal miRNAs in all solid tumor patients. Medicine Baltimore 2019;98:e15335.

- 80. Qu Z, Wu J, Wu J, et al. Exosomal miR-665 as a novel minimally invasive biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis and prognosis. Oncotarget 2017;8:80666-80678.

- 81. Kim HS, Kim JS, Park NR, et al. Exosomal miR-125b exerts anti-metastatic properties and predicts early metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol 2021;11:637247.

- 82. Fang T, Lv H, Lv G, et al. Tumor-derived exosomal miR-1247-3p induces cancer-associated fibroblast activation to foster lung metastasis of liver cancer. Nat Commun 2018;9:191.

- 83. Huang C, Tang S, Shen D, et al. Circulating plasma exosomal miRNA profiles serve as potential metastasis-related biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett 2021;21:168.

- 84. Yap JYY, Goh LSH, Lim AJW, Chong SS, Lim LJ, Lee CG. Machine learning identifies a signature of nine exosomal RNAs that predicts hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers Basel 2023;15:3747.

- 85. Hwang JS, Lee S, Kim G, et al. A serum exosomal microRNA-based artificial intelligence diagnostic model for highly accurate detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Commun (Lond) 2025 Jun 26. doi: 10.1002/cac2.70043.

- 86. Yang Z, Tian T, Kong J, Chen H. ChatExosome: an artificial intelligence agent based on deep learning of exosomes spectroscopy for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis. Anal Chem 2025;97:4643-4652.

- 87. Zhu K, Tao Q, Yan J, et al. Machine learning identifies exosome features related to hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022;10:1020415.