ABSTRACT

Body composition analysis provides essential evidence for evaluating patient health, predicting disease risk, and guiding personalized treatment. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) enables high-resolution visualization of skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and major organs, making it well-suited for constructing 3D anatomical distribution maps. However, current clinical practice largely depends on manual analysis, which is limited in scope, efficiency, and standardization. This review presents recent deep learning techniques, focusing on methods developed by our group, that aim to automate the generation of anatomical distribution maps from abdominal CT. The key topics include: (1) automated localization and identification of the entire spine beyond single-level detection at the third lumbar vertebra (L3); (2) cross-domain consistency learning to overcome limited annotations in medical imaging; (3) multi-organ segmentation that incorporates inter-slice structural continuity and anatomical relationships; and (4) a comparative study of continual learning and multi-dataset learning for building generalizable models. These approaches enable rapid, standardized generation of anatomical distribution maps across large-scale datasets and diverse patient cohorts, providing a robust technical foundation for future precision medicine applications. In particular, these methods are expected to provide for early cancer detection, pediatric CT analysis, and clinical correlation studies linking anatomical distribution maps with outcomes such as cancer prognosis.

-

KEYWORDS: Deep learning; Image processing, computer-assisted; Tomography, X-ray computed; Body composition; Body fat distribution

INTRODUCTION

Obesity currently affects more than 800 million people worldwide. In South Korea, the prevalence of sarcopenia among older adults ranges from 20% to over 60% [

1]. These changes in body composition are closely linked not merely to weight fluctuations, but to major diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic disorders. In particular, sarcopenia has been identified as a critical indicator associated with survival outcomes, postoperative complications, and treatment response in malignancies of the head and neck, breast, lung, and gastrointestinal tract [

2]. As a result, the demand for accurate body composition assessment is steadily increasing across oncology and various other clinical domains.

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) serves as a highly effective modality for this assessment, providing high-resolution visualization of internal anatomical structures, including the musculoskeletal system, adipose tissue, and vital organs. CT-based analysis enables quantitative evaluation of changes in body composition that are directly associated with a patient’s functional status, treatment response, risk of complications, and overall survival. These analyses not only support individual diagnoses but also contribute to population-level disease risk assessment and the development of preventive strategies in large-scale cohorts.

However, traditional body composition analysis has predominantly relied on manual procedures limited to specific anatomical slices. This approach is time-consuming and labor-intensive, and it often results in poor reproducibility due to inter-observer variability. Moreover, relying on a single slice does not sufficiently capture the overall changes in body composition, which limits the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the assessment. Additionally, the lack of standardization caused by variations in imaging devices, acquisition protocols, and anatomical differences among individuals poses a major challenge to large-scale analysis and whole-body assessment.

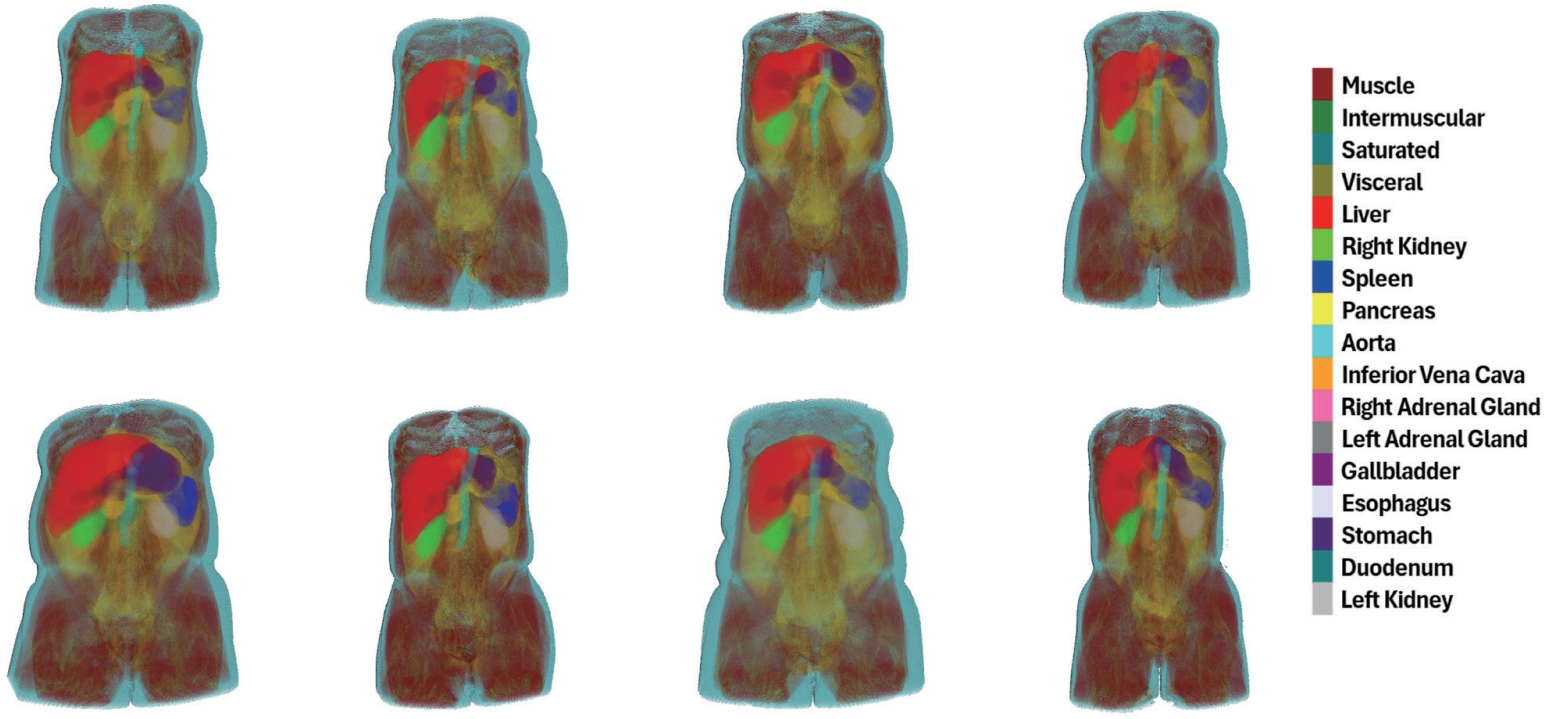

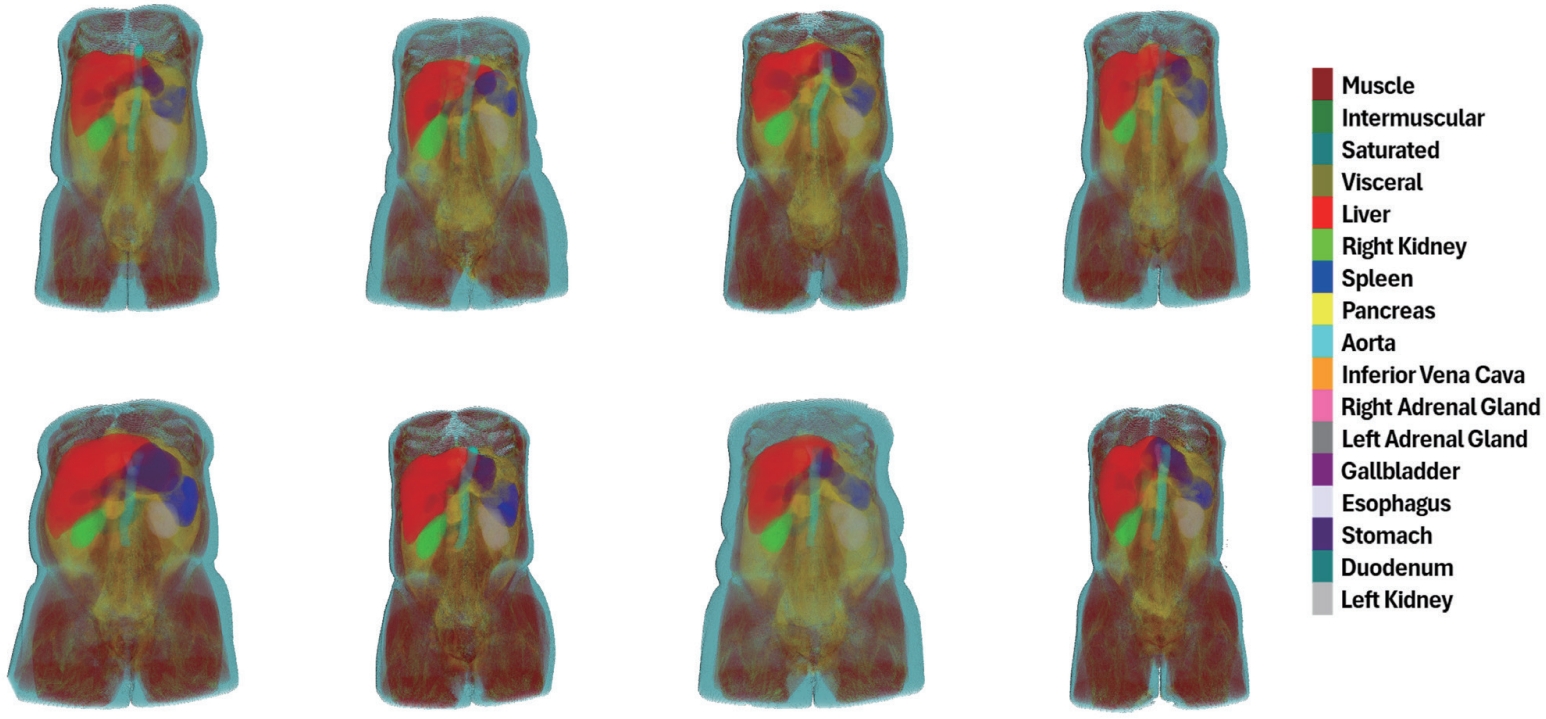

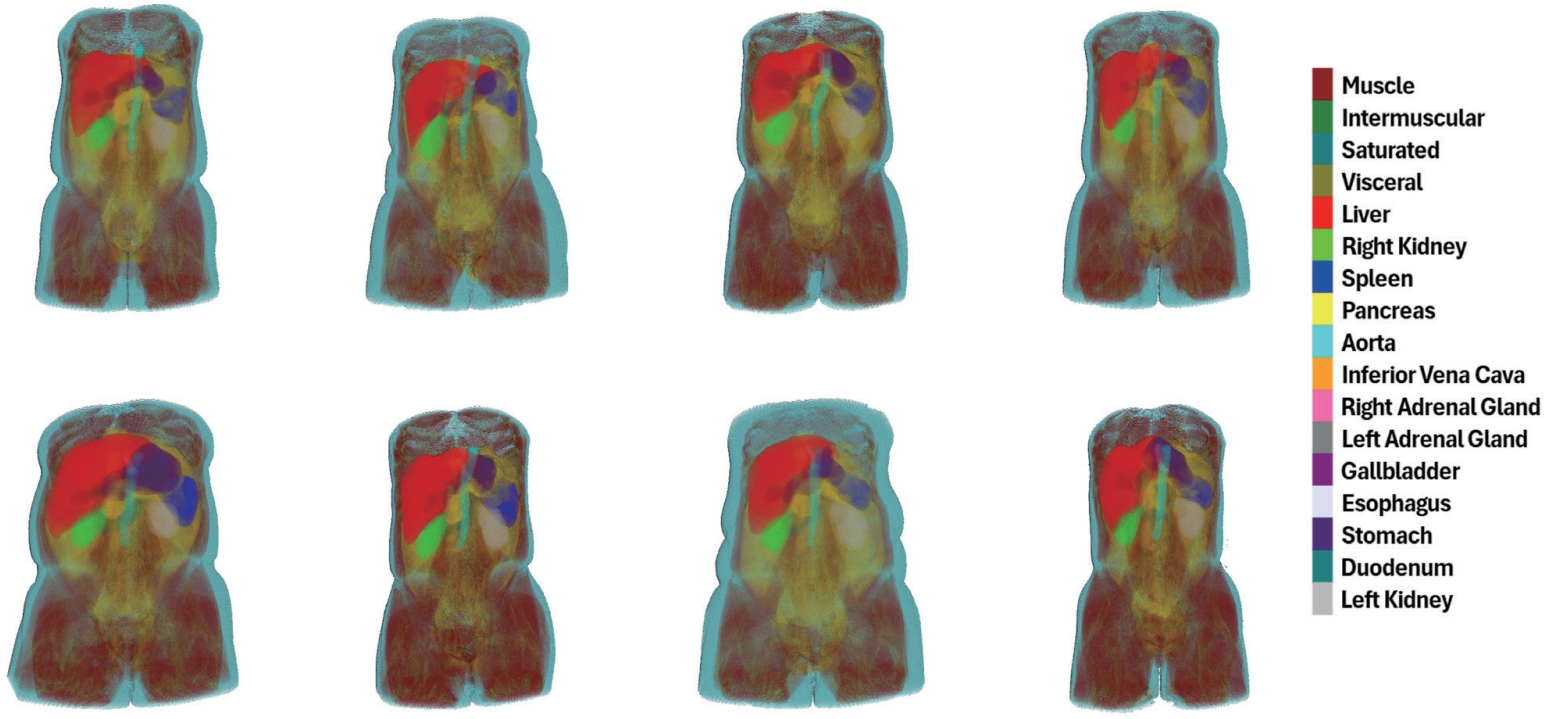

To overcome these limitations, automated imaging analysis techniques powered by deep learning (DL) have recently gained increasing attention. DL enables efficient processing of large-scale abdominal CT data, facilitates precise anatomical analysis, and provides highly reproducible and consistent assessments of body composition. In this review, we present recent DL-based advancements in generating anatomical distribution maps (

Fig. 1) through the automation of body composition analysis using abdominal CT, with a focus on the research conducted by our group. To realize the practical implementation of automated analysis, we propose a series of technical approaches that take into account both the characteristics of abdominal CT and the constraints of clinical environments.

First, we developed a technique for automatically localizing vertebral levels spanning the entire spine (C1–S5), extending the analysis beyond the conventional focus on the L3 slice [

3]. This approach enables comprehensive and standardized body composition assessment by incorporating multiple vertebral levels that also provide clinically meaningful information beyond L3.

In addition, most clinical CT images do not contain manual annotations that indicate the exact anatomical structures, as generating such pixel-level references requires extensive time and expert effort. Therefore, learning strategies that can effectively utilize limited annotation data are essential. To address this issue, we introduced a cross-domain consistency learning method that transfers knowledge learned from a single labeled slice (L3) to the remaining unlabeled slices [

4]. This approach encourages the model to make consistent predictions across slices with different anatomical contexts within the same patient, thereby mitigating the challenges posed by the scarcity of labeled data.

Moreover, capturing the anatomical continuity across adjacent slices and the spatial relationships between organs is crucial for achieving accurate segmentation in 3D CT imaging. To this end, we designed a 2.5D attention-based architecture capable of exchanging contextual information across neighboring slices, and proposed a hierarchical learning strategy that reflects the anatomical adjacency of organ commonly observed in CT scans [

5,

6]. These approaches contribute to improved segmentation accuracy, particularly for organs with complex anatomical structures.

Finally, most existing medical image segmentation models are trained using a single dataset, which limits their ability to generalize across the wide range of anatomical variability and imaging conditions encountered in clinical practice. To overcome this limitation, we applied two representative learning strategies: Multi-Dataset Learning, which simultaneously trains a model across multiple datasets, and Continual Learning, which incrementally expands segmentation capabilities to include new organs or domains [

7,

8]. We conducted a comparative analysis of these two approaches under the same experimental conditions to evaluate their segmentation performance and clinical applicability [

9]. This analysis offers practical insights for selecting effective learning strategies suited for clinical deployment.

AUTOMATED LOCALIZATION AND IDENTIFICATION ACROSS THE ENTIRE SPINE BEYOND L3

In abdominal CT imaging, the L3 slice has been the most widely adopted reference for estimating whole-body muscle and adipose tissue [

10]. The L3 level, located in the mid-lumbar region, provides a large cross-sectional area of skeletal muscle and is less susceptible to progressive changes, thereby allowing stable measurements across diverse patient populations [

11]. Traditionally, radiologists manually identified the L3 level, a process that is time-consuming, labor-intensive, and subject to inter-observer variability. To address these limitations, we developed an automatic L3 detection method [

12]. However, relying solely on the L3 slice may overlook potential opportunities for body composition assessment at other vertebral levels. For instance, indices measured at L1 or T5–T12 have shown strong correlations with those at L3, and in certain contexts have been reported as viable alternatives [

13,

14]. Building upon L3 detection, we further developed an automated localization and identification method across the entire spine (C1–C7, T1–T12, L1–L5) [

3]. This method provides accurate positional and labeling information for each vertebral level, supporting anatomical registration across patients and longitudinal scans. It also lays the foundation for automated vertebral slice extraction. This enables precise body composition analysis throughout the entire spine.

Automating vertebral localization, identification, and segmentation in CT imaging has broad potential applications in spinal image analysis and computer-assisted surgical planning [

15]. Accurate anatomical identification of each vertebral level enables precise description of lesion locations and extents in CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, thereby contributing to the standardization of clinical reporting [

16]. This is particularly useful for determining whether a lesion is confined to a specific vertebral level or spans multiple levels, which is critical for the diagnosis and surgical planning of various spinal disorders such as tumors, infections, and scoliosis [

17].

Moreover, constructing a patient-specific anatomical coordinate system of the spine allows for quantitative monitoring of disease progression by comparing changes at the same anatomical location during follow-up examinations [

18]. Normalizing vertebral levels regardless of scan range or anatomical variation also supports consistent analysis across different imaging protocols and equipment, thereby enhancing the reliability of diagnosis and treatment planning. In addition, accurate identification of specific vertebral levels, including L3, serves as a key preprocessing step for CT-based body composition segmentation. It improves the accuracy of skeletal muscle and fat quantification and enhances the efficiency of automated body composition assessment.

With the growing need for precise vertebral-level analysis in CT imaging, this study focuses on the development of two automated strategies. First, we designed an L3 slice detector with a multi-channel input architecture that enables rapid localization of the L3 slice in abdominal CT scans while reliably capturing its anatomical characteristics. Second, we introduced a contrastive learning-based multi-view vertebral localization and identification model using digitally reconstructed radiograph (DRR) images, which are generated by projecting 3D CT scans from various angles. This approach addresses both the limited availability of annotated data and inter-patient anatomical variability.

Together, these strategies go beyond single-slice analysis by enabling consistent vertebral-level localization and identification across the entire spine. They provide a robust foundation for automating body composition analysis that can be adapted to diverse clinical scenarios and data environments.

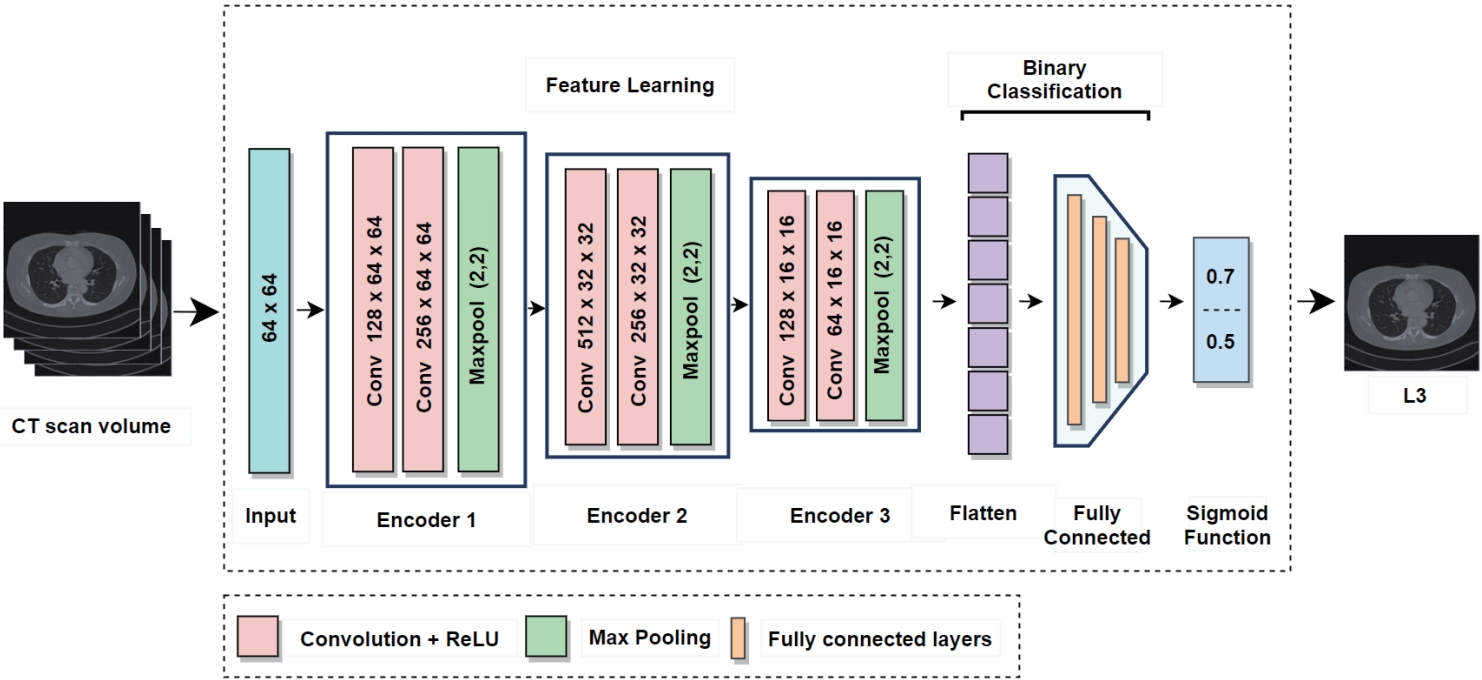

1. L3 Slice detector

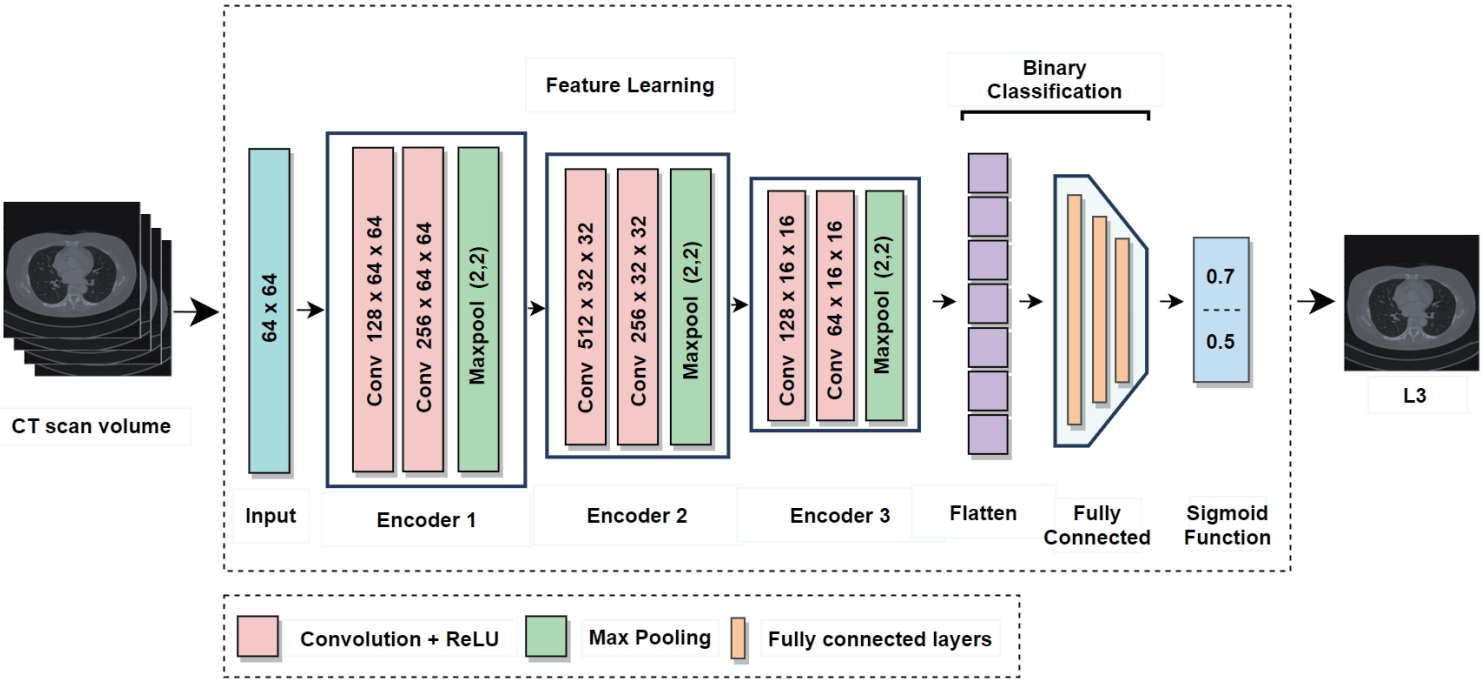

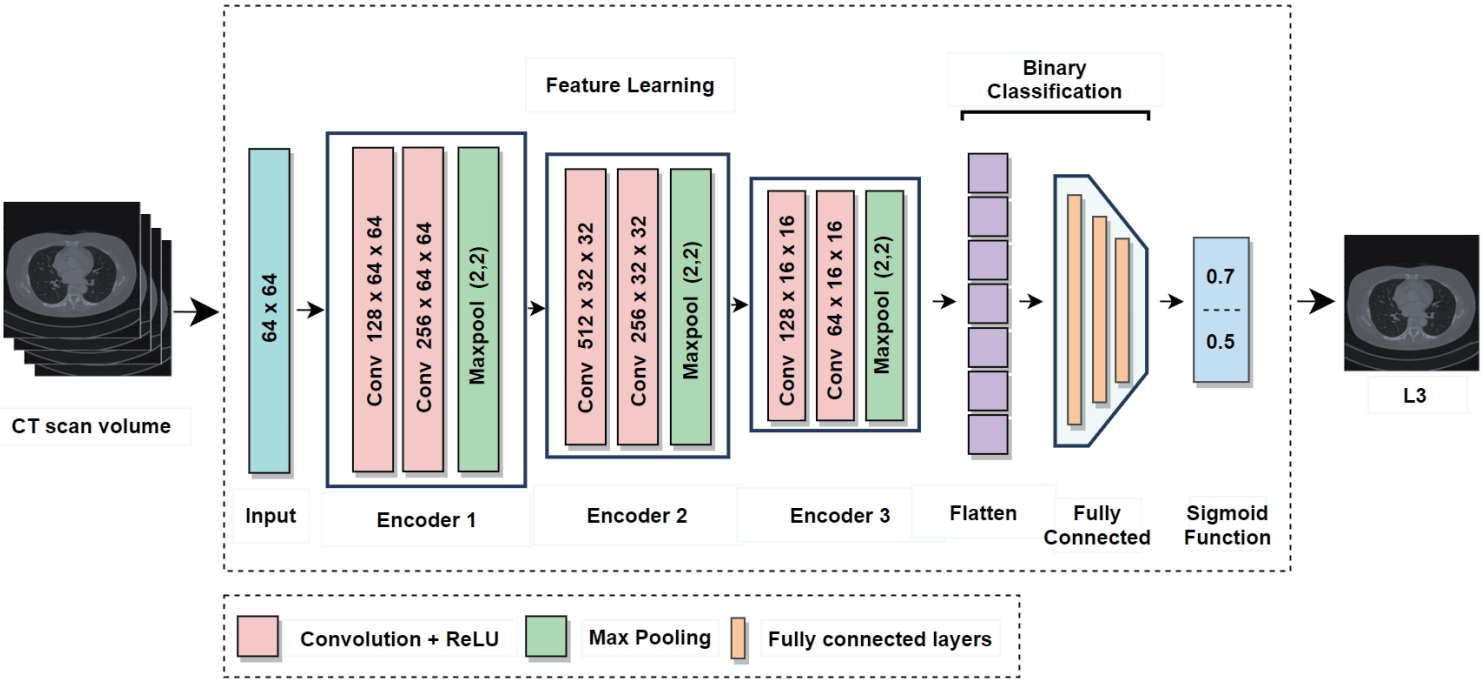

In current clinical practice, body composition analysis using abdominal CT involves radiologists manually identifying L3 slice from the full scan and analyzing it with specialized software. However, this process takes more than five minutes even for experienced radiologists and is subject to inter-observer variability, limiting both efficiency and reproducibility. In particular, slices corresponding to the L3 level account for only a very small portion of the entire CT volume, making it especially challenging to accurately identify them among hundreds of non-L3 slices. To address this challenge, the proposed L3 slice detector (

Fig. 2) sets each CT slice as a central slice and constructs a multi-channel input by stacking it with adjacent slices above and below [

12]. When the central slice is labeled as L3, a pixel unshuffled operation is applied to reduce its spatial resolution while increasing the number of channels [

19]. This transformation preserves detailed spatial information and enhances the model's robustness against anatomical variability and acquisition differences across patients.

In contrast, the adjacent slices above and below are progressively downsampled with fewer channels, providing contextual anatomical information. The resulting input (e.g., 22 channels at a resolution of 64×64) is fed into the model, which outputs a probability score (ranging from 0 to 1) indicating whether the central slice corresponds to the L3 level. The model sequentially processes all slices in the CT volume, computes the L3 probability for each, and selects the slice with the highest probability as the final L3 candidate. If necessary, a predefined threshold (e.g., 0.5) can be used to determine the absence of L3 when no slice exceeds the threshold.

In this study, the model was trained and evaluated using abdominal CT scans from 200 patients collected at Kyungpook National University Hospital. Each scan included an expert-annotated L3 slice, with data from 160 patients used for training and 40 patients reserved for validation. The model performance was evaluated using precision (true positives among predicted positives), recall (true positives among actual positives), specificity (true negatives among actual negatives), and the F1-score, which is the harmonic mean of precision and recall. Experimental results showed that the proposed multi-channel input strategy significantly outperformed the single-channel approach (

Table 1). These findings demonstrate the feasibility of integrating L3 slice detection with muscle and fat segmentation in a fully automated pipeline.

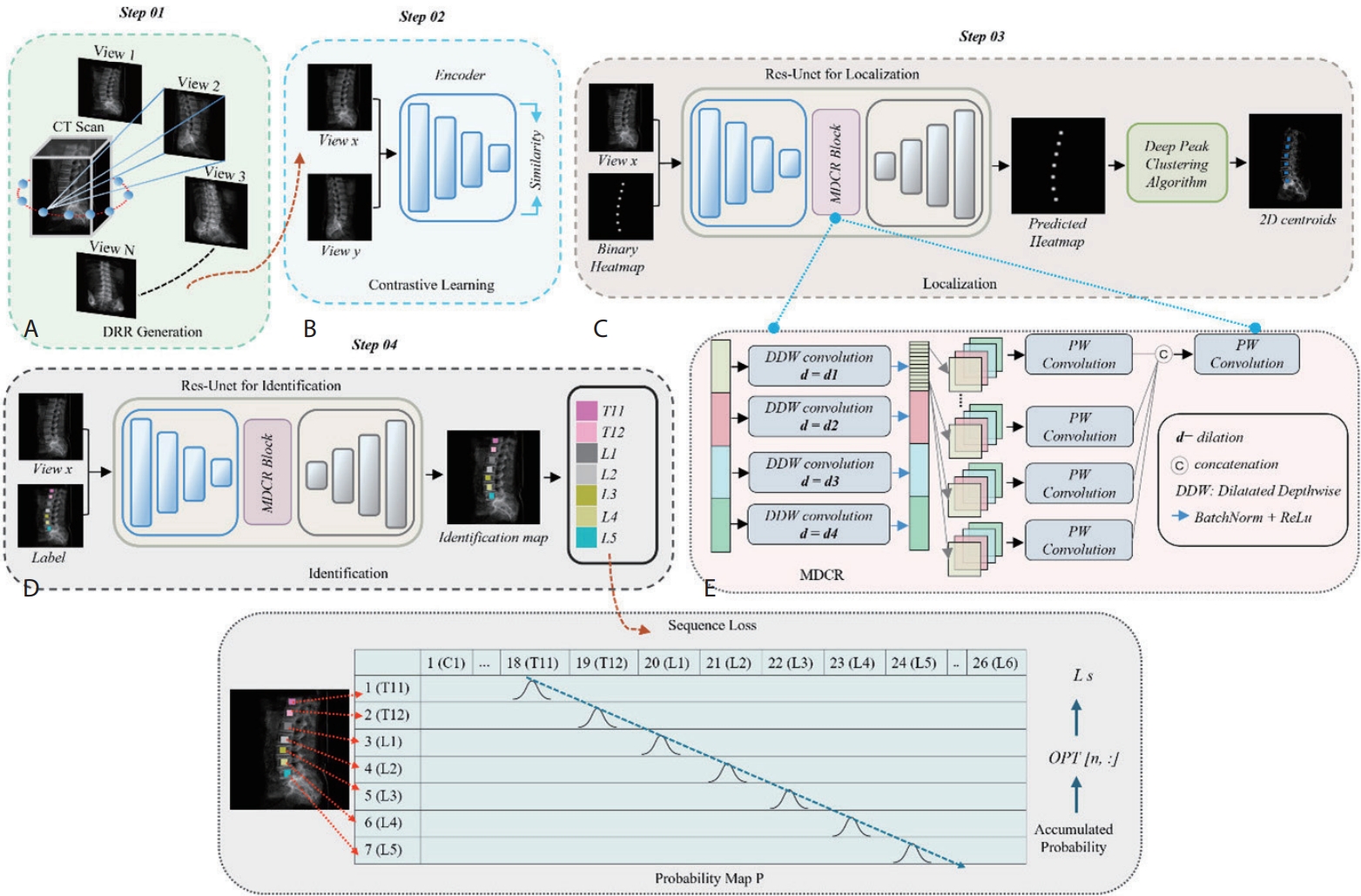

2. Vertebrae localization and identification

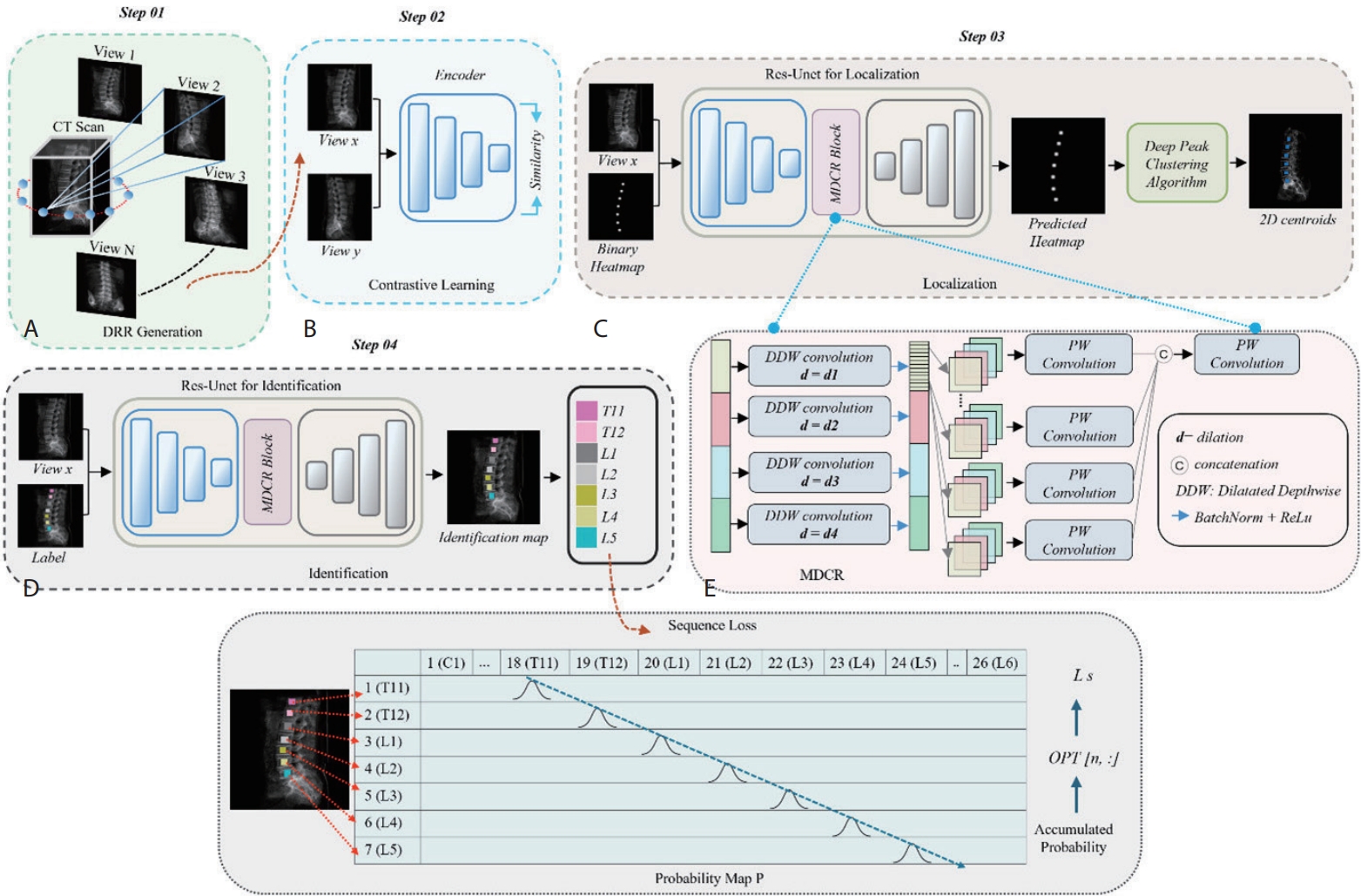

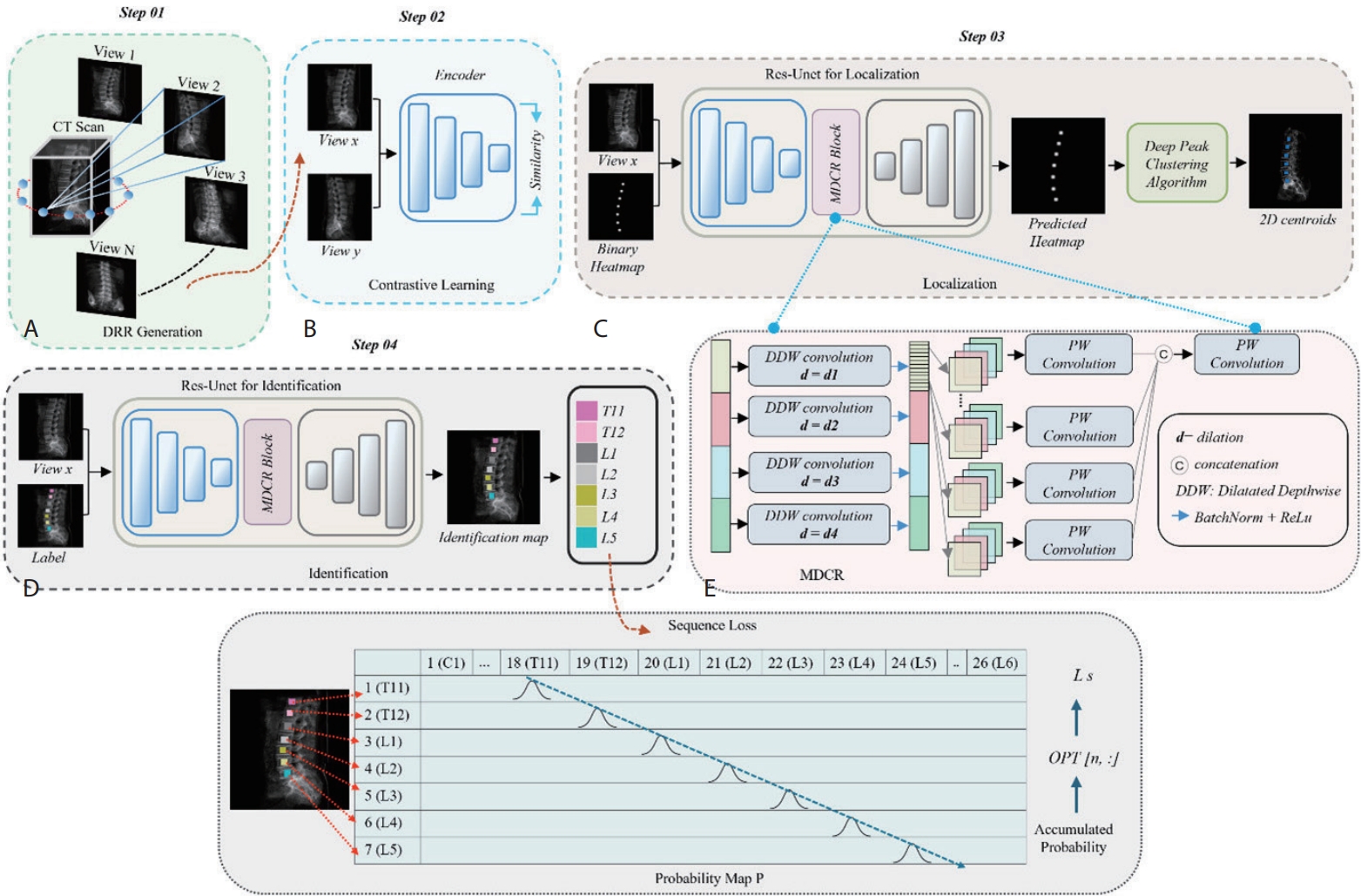

In light of the clinical importance of vertebral localization and identification, we propose a multi-view learning method (

Fig. 3) to automatically localize and identify vertebral centroids in DRR images [

3]. DRR images are 2D X-ray-like projections generated from 3D CT volumes at various viewing angles, resembling actual radiographs.

In the multi-view DRR generation stage (Step 01), we generate DRRs from multiple angles per CT scan to enable a multi-view learning strategy, particularly effective under limited data conditions. This allows the model to learn view-invariant vertebral features, leading to more reliable identification under varying imaging conditions.

In the contrastive learning stage (Step 02), vertebrae from different views of the same patient are trained to map closely in the embedding space, while different vertebrae are mapped farther apart. As a result, the model can learn robust representations that consistently recognize spinal structures regardless of the viewing angle.

In the localization stage (Step 03), the model detects the centroid of each vertebral body in the DRR image. This model was trained to generate heatmaps that highlight areas likely to contain the spine, from which precise center points are extracted using the deep peak clustering algorithm [

20].

In the identification stage (Step 04), the surrounding region of each centroid is analyzed to assign the corresponding vertebral label. To enforce anatomical ordering from cranial to caudal direction, a sequence loss is applied to discourage incorrect vertebral labeling sequences [

21].

Based on the VerSe 2019 CT dataset for vertebral localization and identification, we generated 10 DRR images per scan, resulting in 670 DRRs, which were used to train our localization and identification networks [

18]. For evaluation, 340 DRRs were generated from 34 patient CT scans. The model achieved a mean localization error (L-Error) of 1.64 mm, where L-Error represents the average Euclidean distance between the predicted and ground-truth vertebral centroids. This performance was validated through comparison with state-of-the-art methods proposed by Payer et al. [

22], Sekuboyina et al. [

23], and Wu et al. [

21], where our approach achieved the lowest localization error. However, the identification rate was lower than that of existing methods, primarily due to cascading errors from misidentifying the first visible vertebra in certain patients' DRRs (

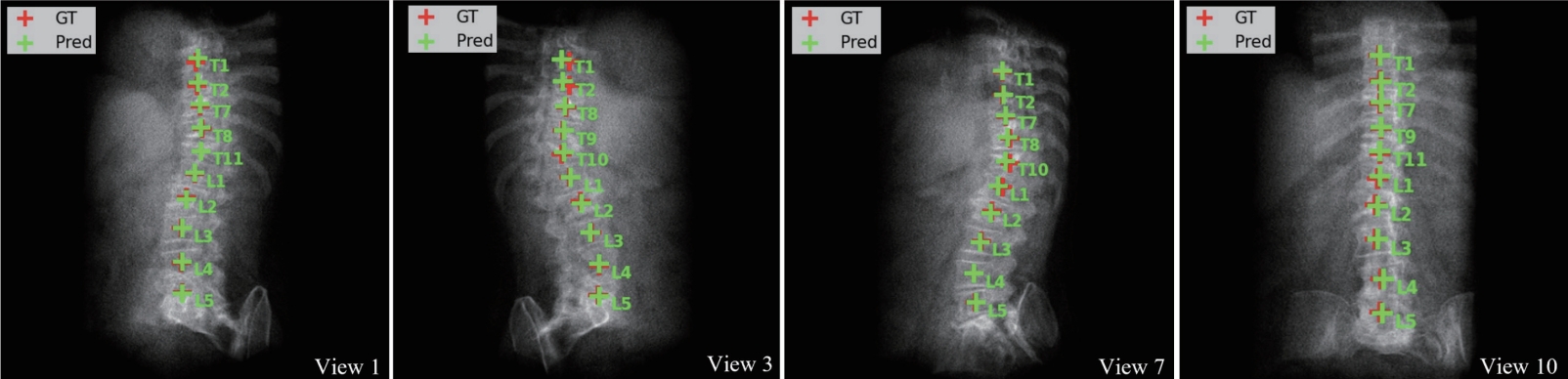

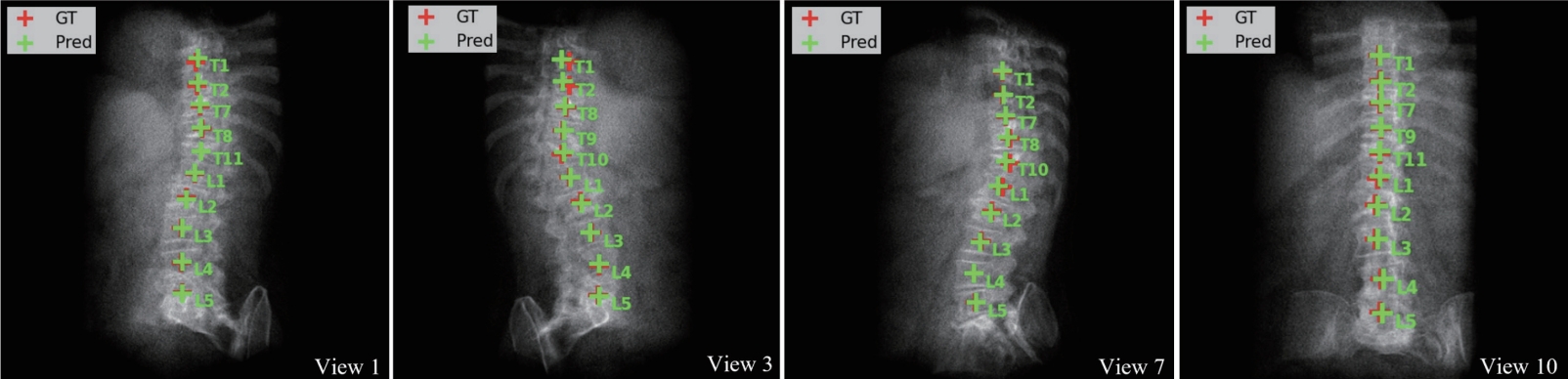

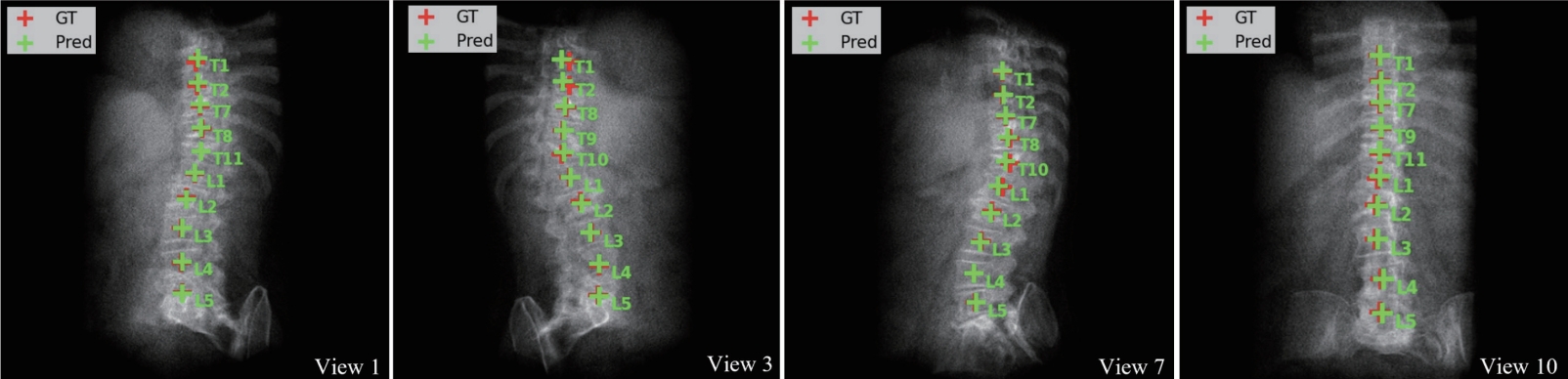

Table 2). The identification rate (Id-Rate) quantifies the proportion of correctly labeled vertebrae in the image. For instance, in the case shown in

Fig. 4, T8 was incorrectly predicted as T1, causing subsequent vertebral labels to shift accordingly. Such errors are inherent to the sequence loss framework, which enforces ordinal constraints; future work may address this by incorporating anchor-based identification.

BODY COMPOSITION SEGMENTATION

Traditional indices for assessing body composition include body mass index, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and body adiposity index [

24]. However, these indices are based on population-level assumptions and have limitations in directly reflecting the detailed body composition of individual patients [

25]. In particular, skeletal muscle mass can vary significantly even among individuals with the same height and weight, and this difference has a major impact on functional status and disease prognosis. Therefore, accurate measurement is essential for clinical evaluations that rely on skeletal muscle mass [

26,

27].

In response to this need, deep learning-based body composition segmentation techniques have gained increasing attention. These techniques use three-dimensional medical images to automatically classify muscle and fat tissues at the pixel level, enabling precise quantification of the body’s composition distribution. Such automated approaches facilitate rapid and consistent body composition analysis not only in large-scale cohort studies but also in clinical practice, and are expected to serve as a key foundation for the development of personalized treatment strategies in the future.

Clinical Applications

Body composition analysis plays a critical role not only in individual patient diagnosis, but also in predicting prognosis and establishing population-level baselines based on large-scale cohort data. Jung et al. [

28] utilized the UK Biobank and German National Cohort datasets to quantify subcutaneous adipose tissue, visceral adipose tissue, skeletal muscle (SM), and intermuscular adipose tissue (IMAT) volumes from whole-body MRI using a deep learning-based segmentation model. Their analysis demonstrated that greater SM volume was associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality, whereas higher IMAT volume was linked to increased mortality. These findings establish SM and IMAT as key variables in survival prediction and highlight the potential of body composition metrics to guide patient risk stratification and treatment planning.

Furthermore, Magudia et al. [

29] constructed age-, sex-, and race-specific reference curves for body composition using abdominal CT data from a large outpatient population with no history of cardiovascular disease or cancer. By employing deep learning-based automated segmentation and area calculation of the L3 slice, they developed reference standards that reflect large-scale patient data. These curves allow for the rapid assessment of whether an individual’s body composition metrics fall within normal ranges and can serve as a foundational tool for disease risk evaluation and treatment strategy development.

Unlike natural image datasets, medical imaging datasets require expert annotation, where clinicians must meticulously label each pixel according to its corresponding anatomical structure. As a result, the availability of ground truth labels is extremely limited. This limitation is particularly evident in abdominal CT datasets for body composition segmentation, where hundreds of slices exist per patient and precise annotation is required. Consequently, obtaining labels for all CT slices and applying fully supervised learning (where ground truth is provided for all training data) is practically infeasible.

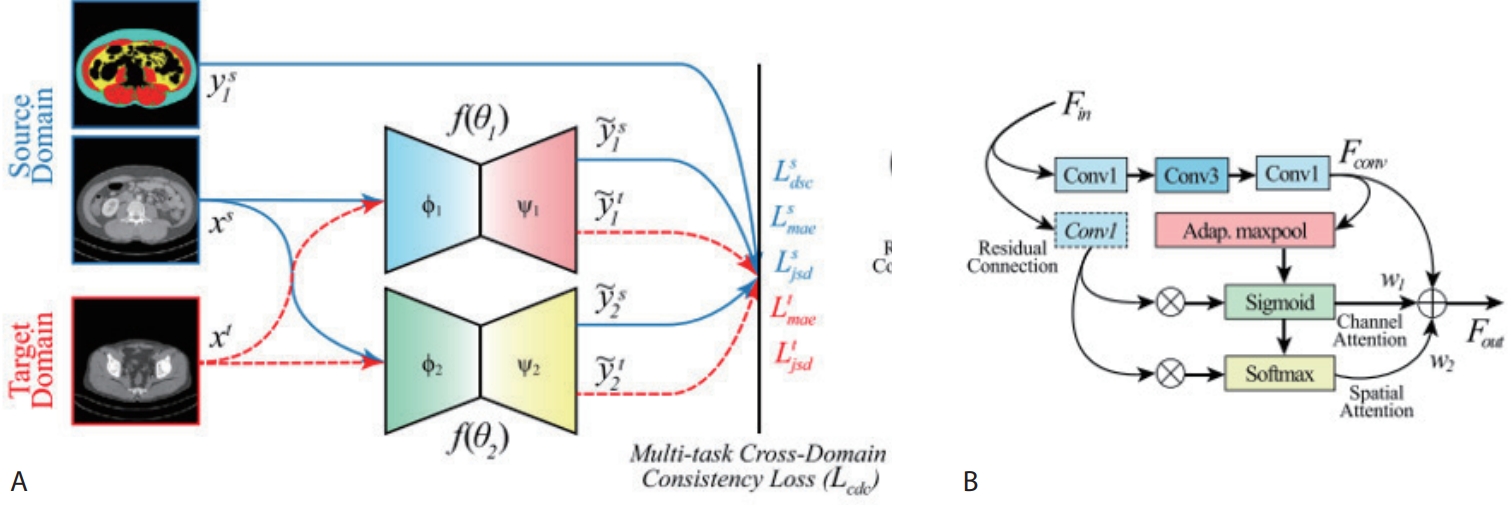

To address this challenge, we propose a Cross-Domain Consistency Learning (CDCL) method that enables body composition segmentation across the entire CT volume, even when ground truth annotations are available for only a single slice—specifically, the L3 slice [

4].

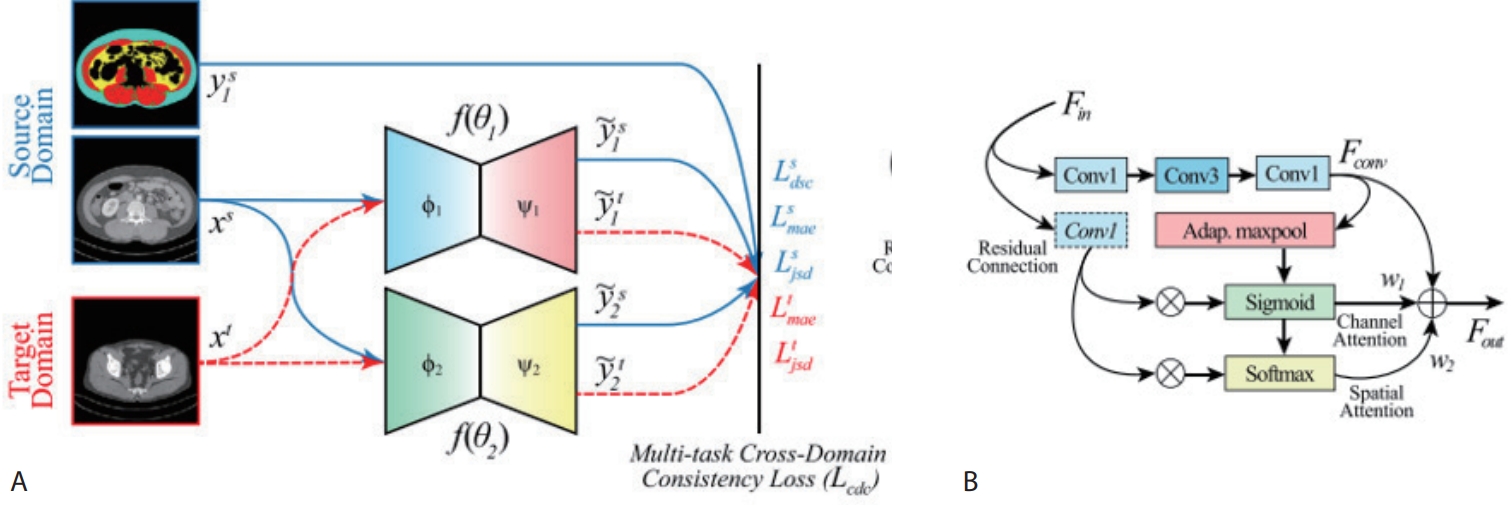

1. Unsupervised domain adaptation by cross-domain consistency learning

When a model is trained solely on the L3 slice, its performance tends to degrade when applied to slices from other vertebral levels (e.g., thoracic, lumbar, sacral), due to differences in tissue distribution across anatomical regions. This phenomenon, known as domain shift, occurs when there is a mismatch in data distribution between the training and inference phases.

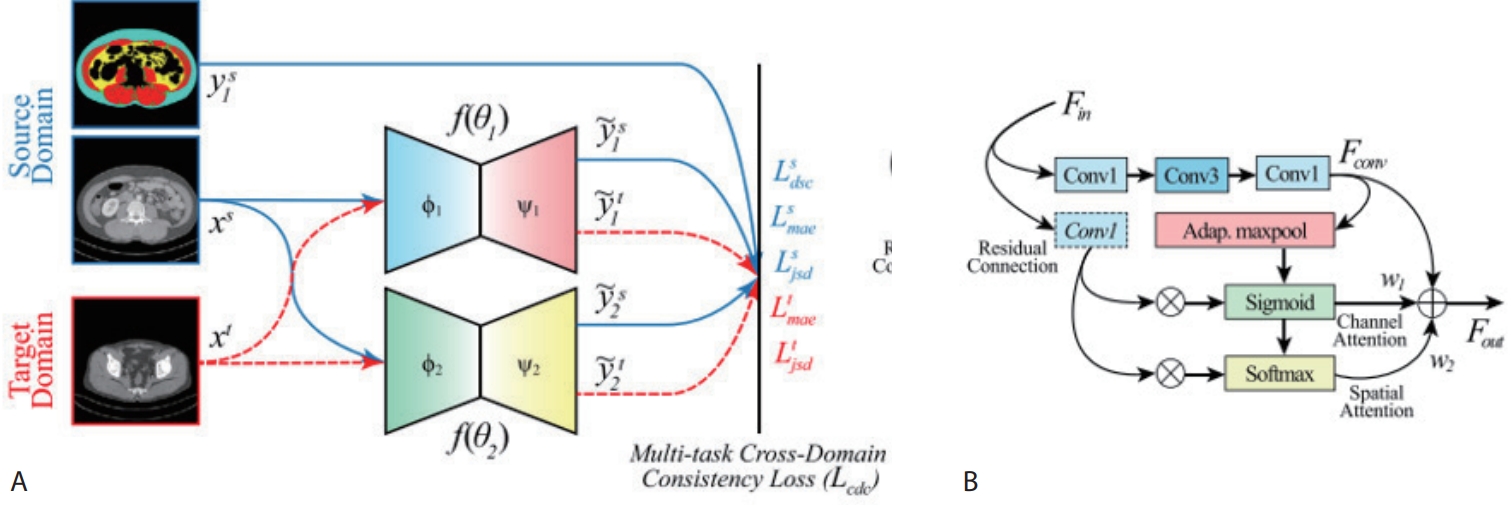

To address this problem, we propose a method called CDCL. In brief, we treat the annotated L3 slice as the

source domain and the remaining unannotated non-L3 slices as the

target domain, and train the model to produce consistent predictions across both domains. To this end, we construct two lightweight encoder–decoder networks (

Fig. 5) with identical architectures but different random initializations. For annotated data such as the L3 slice, we apply conventional supervised learning. For unlabeled CT slices, we encourage the two networks to produce similar predictions, thus providing additional learning signals.

To enforce prediction consistency, we utilize the Jensen–Shannon Divergence loss, which quantifies the similarity between two probability distributions on a scale from 0 to 1, with lower values indicating higher similarity. By minimizing this loss, the two networks are guided to produce more consistent outputs for the same input, even in the presence of noisy or variable data.

Through this approach, the model learns to generalize the knowledge acquired from the L3 slice—such as the shapes, locations, and boundaries of muscle and fat—to other anatomical regions. This enables stable segmentation performance across unlabeled slices. Notably, significant performance improvements were observed in the segmentation of IMAT, which is typically small in volume and exhibits ambiguous boundaries. Furthermore, since only one of the networks is used during inference, the computational overhead is minimal, making the method feasible for real-world clinical deployment. To validate the effectiveness of CDCL, we conducted experiments using abdominal CT data collected from Kyungpook National University Hospital (KNUH). The dataset consists of two components:

• The source domain (L3 dataset) includes 1,004 axial CT slices centered at the third lumbar vertebra (L3), of which 804 were used for training and 200 for validation.

• The target domain (T1S5 dataset) contains 424 slices sampled from 22 vertebral levels spanning from thoracic vertebra 1 (T1) to sacral vertebra 5 (S5); among these, 338 were used as unlabeled training inputs, and 86 were used for validation.

Experimental results demonstrated that CDCL outperformed conventional transfer learning (TL), achieving an average improvement of 3.31% in dice similarity coefficient (DSC) and 4.4% in intersection-over-union (IoU) across all classes (

Table 3). In particular, segmentation of IMAT showed a substantial improvement, with an increase of 11.48% in DSC and 14.11% in IoU. Both DSC and IoU evaluate the degree of overlap between predicted and ground-truth segmentations. DSC, calculated as twice the intersection divided by the sum of predicted and ground-truth regions, is more sensitive to small structures. In contrast, IoU, defined as the intersection over the union of the two regions, provides a stricter criterion for overlap. Together, these complementary metrics offer a comprehensive assessment of segmentation performance.

While TL leverages weights from a model pre-trained on one domain and fine-tunes it on a new domain—thus reducing training time—it remains vulnerable to performance degradation when the source and target domains differ substantially. The results of this study demonstrate that CDCL effectively addresses these limitations

MULTI-ORGAN SEGMENTATION

Multi-organ segmentation refers to the task of simultaneously identifying and accurately delineating multiple organs within medical images, such as CT scans. The goal is to assign each voxel in the complex 3D anatomical structure to its corresponding organ with high precision. Traditionally, this process required skilled experts to manually identify and segment hundreds of CT slices. However, this approach is challenging for organs that are difficult to distinguish visually, time-consuming, and demands a high level of expertise. Moreover, achieving consistency across annotators is difficult.

Against this backdrop, deep learning–based automated multi-organ segmentation techniques have recently advanced rapidly. These methods provide consistent and repeatable segmentation results, making them a core technology for improving the efficiency and reliability of medical image analysis.

Clinical Applications

For accurate radiotherapy planning, it is essential to precisely delineate not only the lesion but also the boundaries of critical organs, known as organs-at-risk. This delineation directly impacts the definition of the radiation exposure area and the protection of healthy tissues. In this context, deep learning–based multi-organ segmentation models can automatically identify and accurately segment multiple key organs. This automation transforms the workflow by reducing the need for manual contouring to only minor adjustments, significantly shortening the time required for radiotherapy planning and enabling more efficient and consistent treatment strategies [

30]. Such automation technologies are expected to have even greater clinical benefits in scenarios that require repeated planning, such as adaptive radiotherapy, and they have the potential to be integrated into clinical workflows as a foundational tool for precision medicine.

Additionally, the results of multi-organ segmentation provide the foundational data to quantify the shape and position of individual organs. Among these, organ volume serves as a critical clinical indicator in various scenarios. In particular, the volumes of major organs are important biomarkers for disease diagnosis, severity assessment, treatment response monitoring, and prognosis prediction. For example, conditions such as hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and renal atrophy are associated with diseases like cirrhosis, hematologic malignancies, and chronic kidney disease. Accurate volume measurements of these organs are useful for early detection and monitoring of pathophysiological changes [

31]. Traditionally, organ volumes were either measured manually or estimated based on diameters, but the advancement of deep learning–based multi-organ segmentation technologies now enables more precise and consistent volume measurements.

To address clinical demands, this study proposes a technical approach that leverages the structural characteristics of CT images to improve multi-organ segmentation performance. In particular, we introduce two strategies designed to effectively capture the inherent properties of medical imaging: structural continuity across slices and anatomical consistency across patient scans [

5,

6]. Furthermore, aiming to develop a generalized multi-organ segmentation model suitable for real-world clinical deployment, we comparatively analyze the performance of two representative training strategies under identical conditions: continual learning and multi-dataset learning [

9].

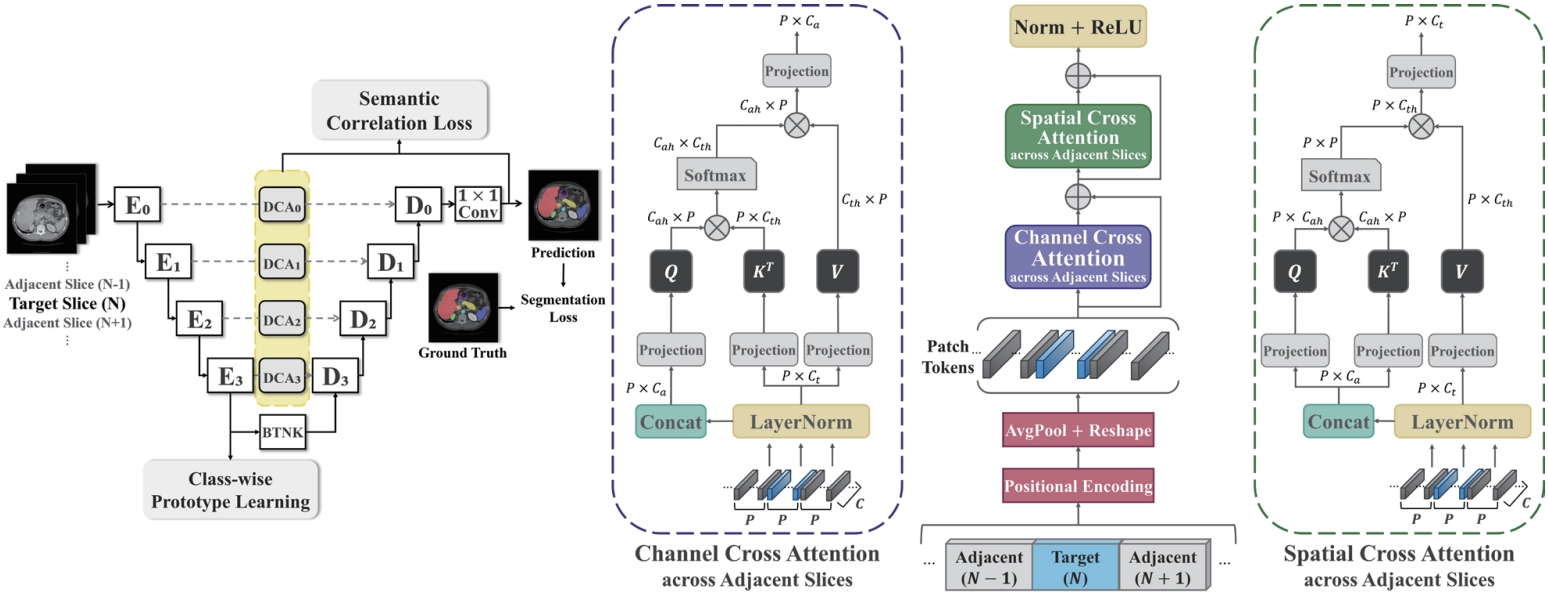

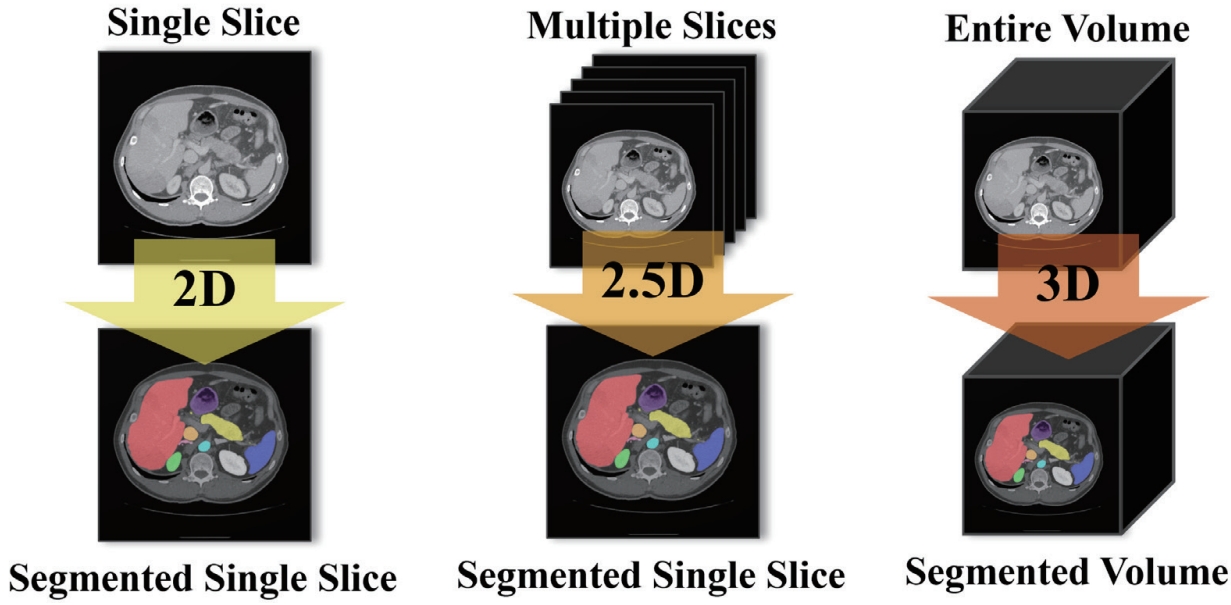

1. Attention-based 2.5D architecture for inter-slice continuity

Since axial CT slices form a continuous anatomical structure along the Z-axis, reflecting this anatomical continuity is critical for improving segmentation performance. While 3D segmentation models have been actively explored to capture the full spatial structure, they are often limited by high computational demands and extensive GPU memory usage. In contrast, 2D segmentation models require less computing resources, but they fail to account for 3D context in CT volumes, resulting in performance degradation for organs with large or complex structural variations between slices. As a result, there is growing interest in 2.5D segmentation models, which can effectively incorporate 3D context under resource-constrained environments.

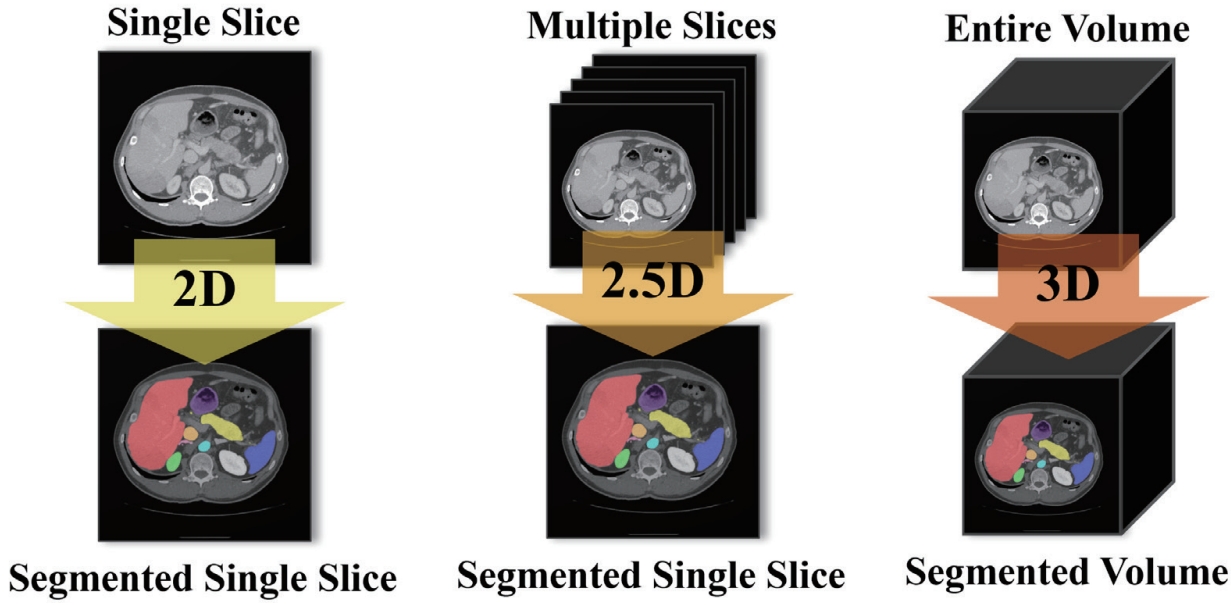

As illustrated in

Fig. 6, a 2D model takes a single slice as input and predicts the segmentation for that slice only. A 2.5D model uses multiple adjacent or multi-view slices along with the target slice to enhance its anatomical context and improve segmentation prediction. Finally, a 3D model takes the entire CT volume as input and performs segmentation across the whole volume. Conventional 2.5D segmentation approaches often stack multiple adjacent slices along the channel dimension. However, such naïve stacking fails to adequately capture the continuous changes and anatomical connections of organs between slices.

To address this limitation, recent studies [

32-

35] have proposed more refined methods to model the inter-slice relationships. However, these methods often lack consideration for global dependencies that capture relationships between distant anatomical structures. Even when such dependencies are considered, they mainly focus on slice-level or spatial global relationships, failing to fully exploit the important image-level information embedded in individual channels.

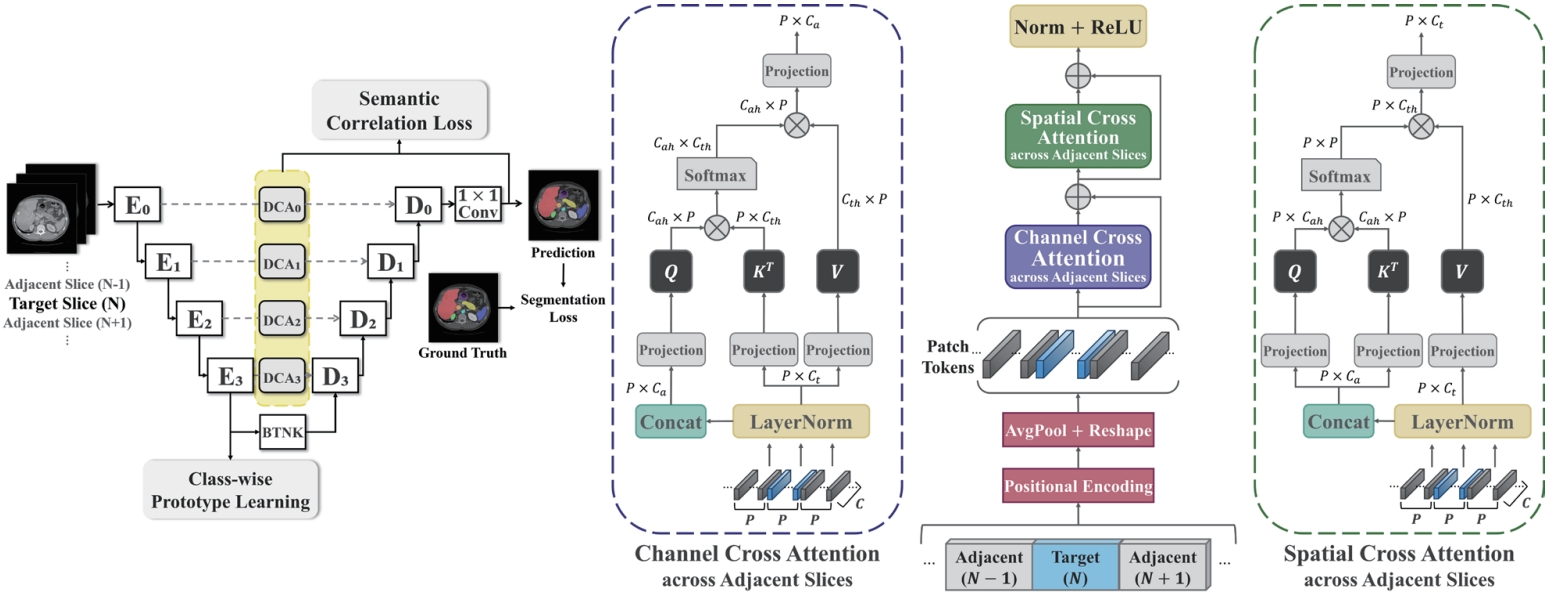

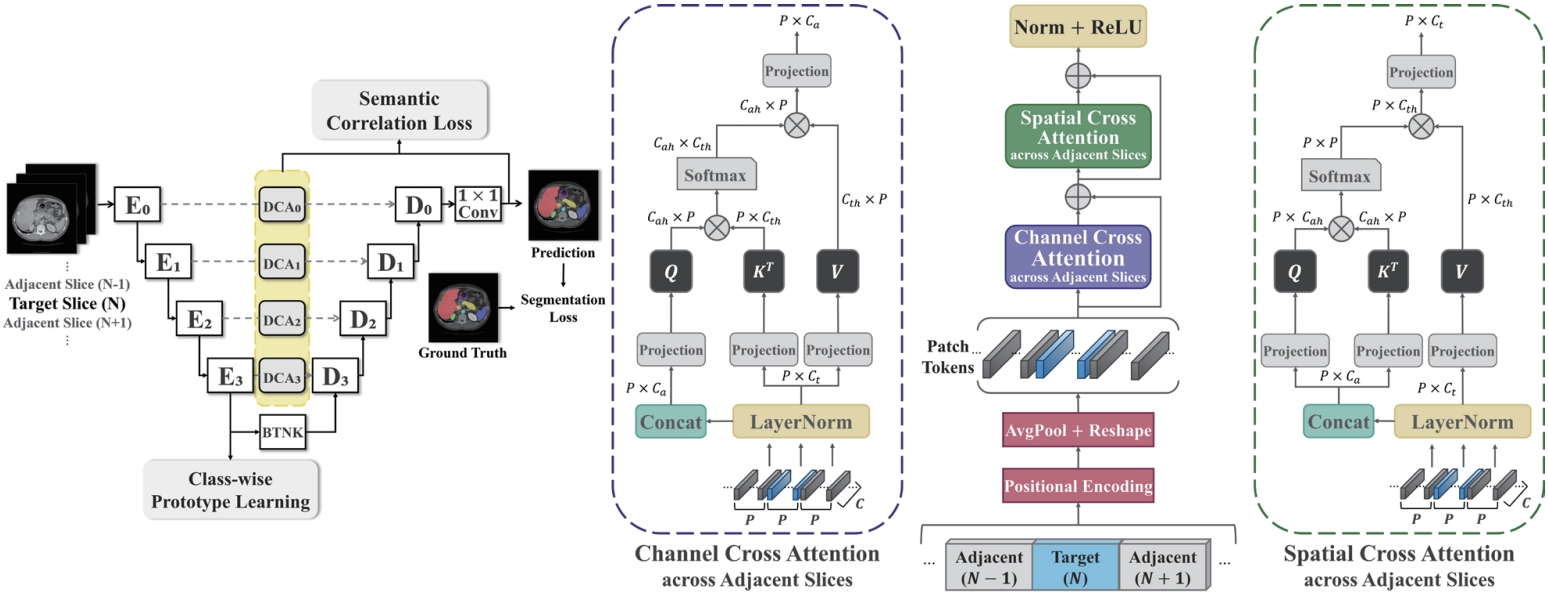

As shown in

Fig. 7, this study proposes a novel architecture—dual cross attention (DCA) module—that simultaneously captures spatial and channel-wise relationships across adjacent slices by comprehensively addressing the strengths and limitations of previous methods. The proposed DCA module is integrated into the skip connections of the U-Net architecture [

36]. U-Net-based models are widely adopted in medical image segmentation due to their ability to capture both the global shape and fine anatomical details of organs. A core component of this architecture, the skip connection, directly links the encoder—which compresses the input image and extracts features—with the decoder, which reconstructs the segmentation output. This connection helps restore anatomical details (e.g., organ boundaries and locations) that may be lost during the downsampling process.

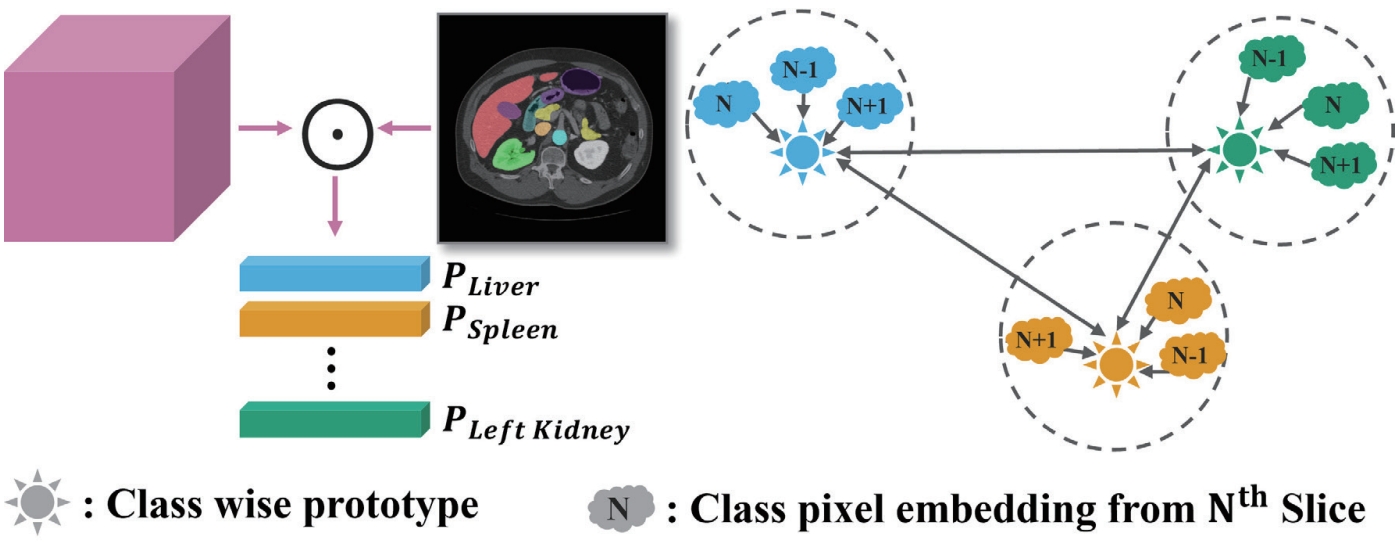

In this study, we leverage the skip connection pathway by incorporating the DCA module, which captures spatial and channel-wise dependencies across adjacent slices, enabling the decoder to generate more precise segmentation results based on richer anatomical context. Additionally, as shown in

Fig. 8, we introduce class-wise prototype learning (PL) to ensure consistent representation of the same anatomical structure (class) across adjacent slices. By learning representative prototypes for each organ class, the model can recognize the same organ even when its shape or intensity varies across slices. We also apply a semantic correlation loss (SC) that aligns the internal representation (DCA features) with the decoder’s output using cosine similarity. The calculated similarity is compared against the ground-truth class presence in the slice, encouraging each feature channel to specialize in representing a specific organ.

To validate the effectiveness of our approach, we conducted experiments on an abdominal CT organ segmentation public dataset FLARE22 [

37], using 3,846 slices from 40 patients for training and 948 slices from 10 patients for evaluation. An ablation study on the FLARE22 dataset (

Table 4) was performed to compare our method against 2D and 2.5D baselines. Compared to the 2D baseline (88.35% DSC), the naïve 2.5D input using simple channel stacking slightly degraded performance to 88.02%, revealing the limitations of this approach. In contrast, incorporating the DCA module significantly improved performance to 90.55%. Adding the Prototype Learning and Semantic Correlation loss modules further enhanced the results, with the full model (DCA + PL + SC) achieving a mean DSC of 91.84%, representing a 3.49% improvement over the 2D baseline.

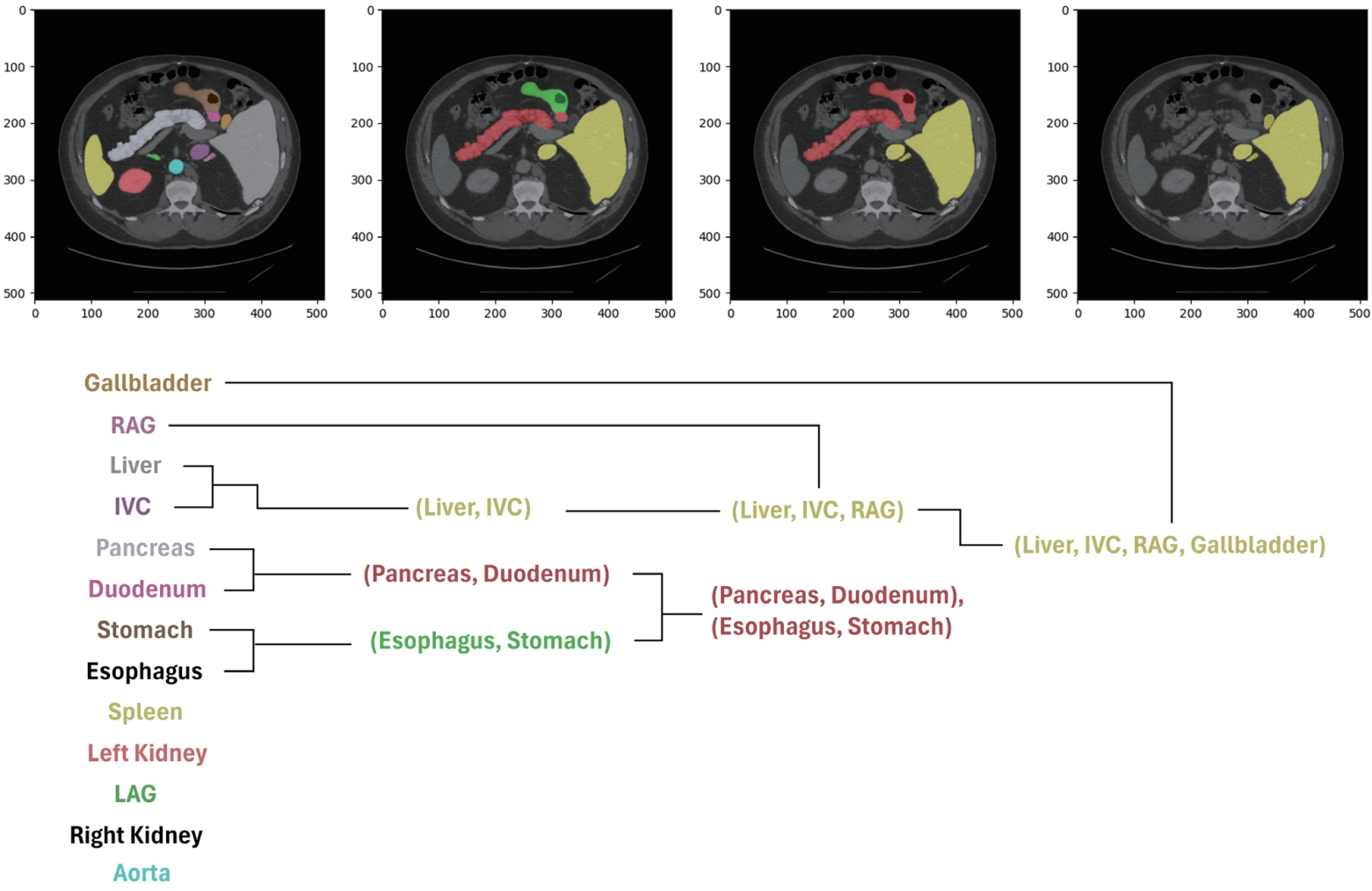

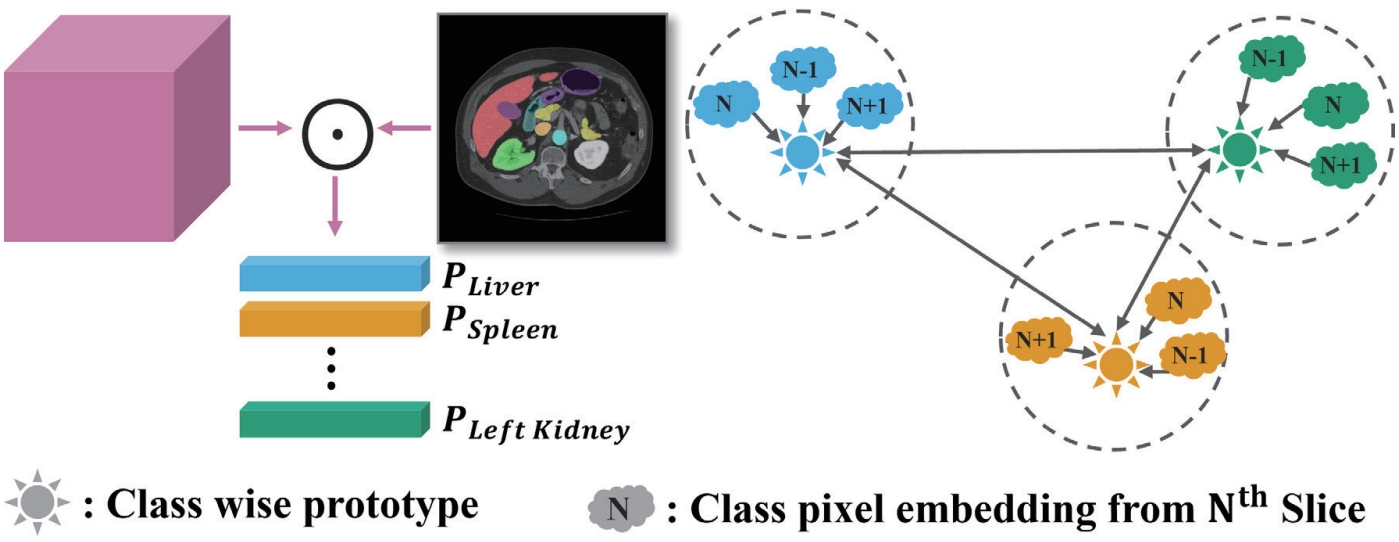

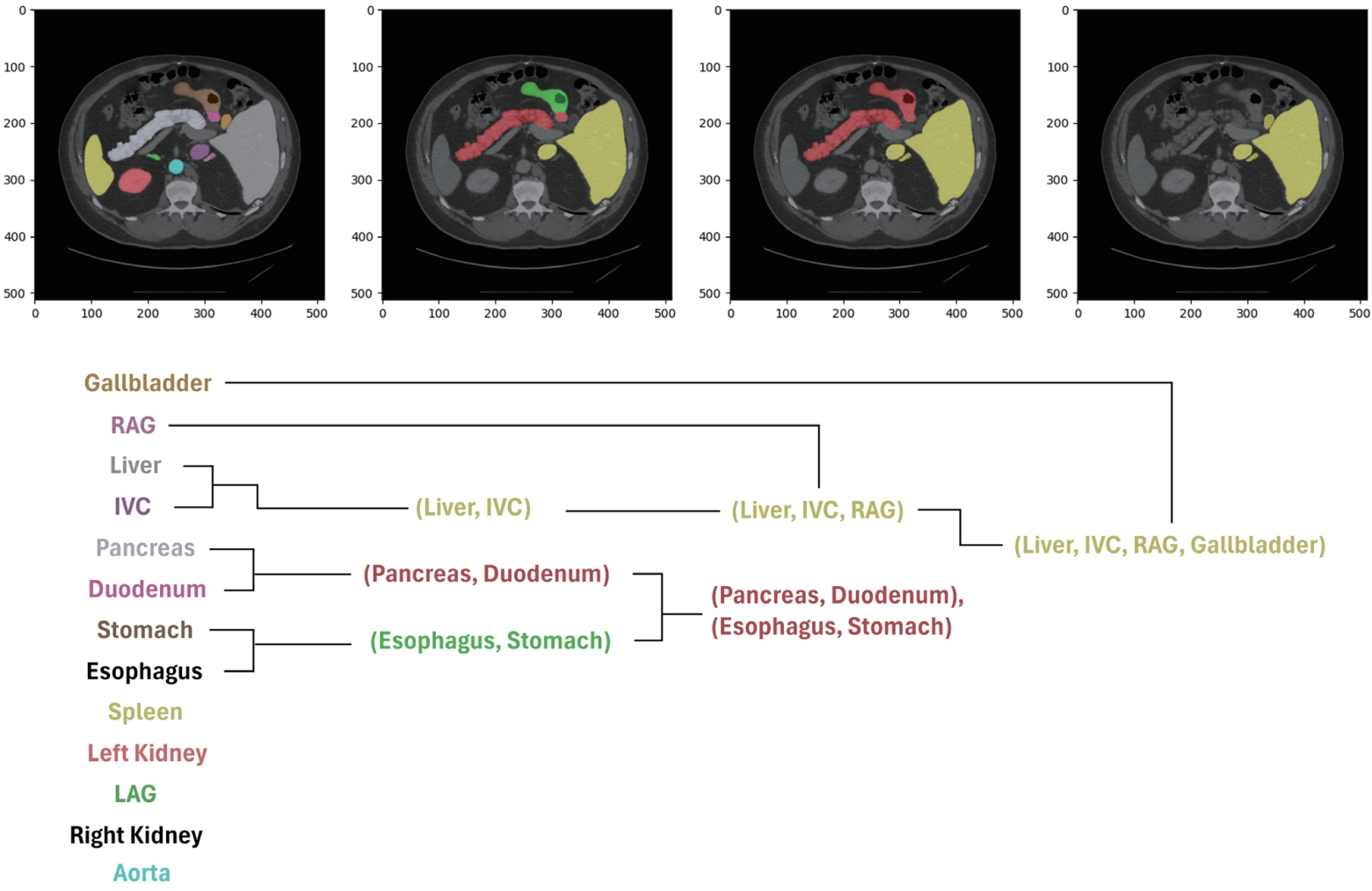

2. Hierarchical segmentation for learning anatomical consistency across patient scans

Conventional medical image segmentation models typically predict the anatomical class of each pixel independently, often failing to capture the structural relationships or anatomical context between organs. To address this limitation, we draw inspiration from hierarchical prediction models that leverage semantic class hierarchies, which have been widely explored in the natural image domain. For instance, Li et al. [

38] proposed a hierarchical segmentation model that enforces consistency between parent and child class predictions—e.g., grouping “sedan” and “truck” under “car,” or “dog” and “cat” under “animal”—which has shown promising results for general object segmentation tasks.

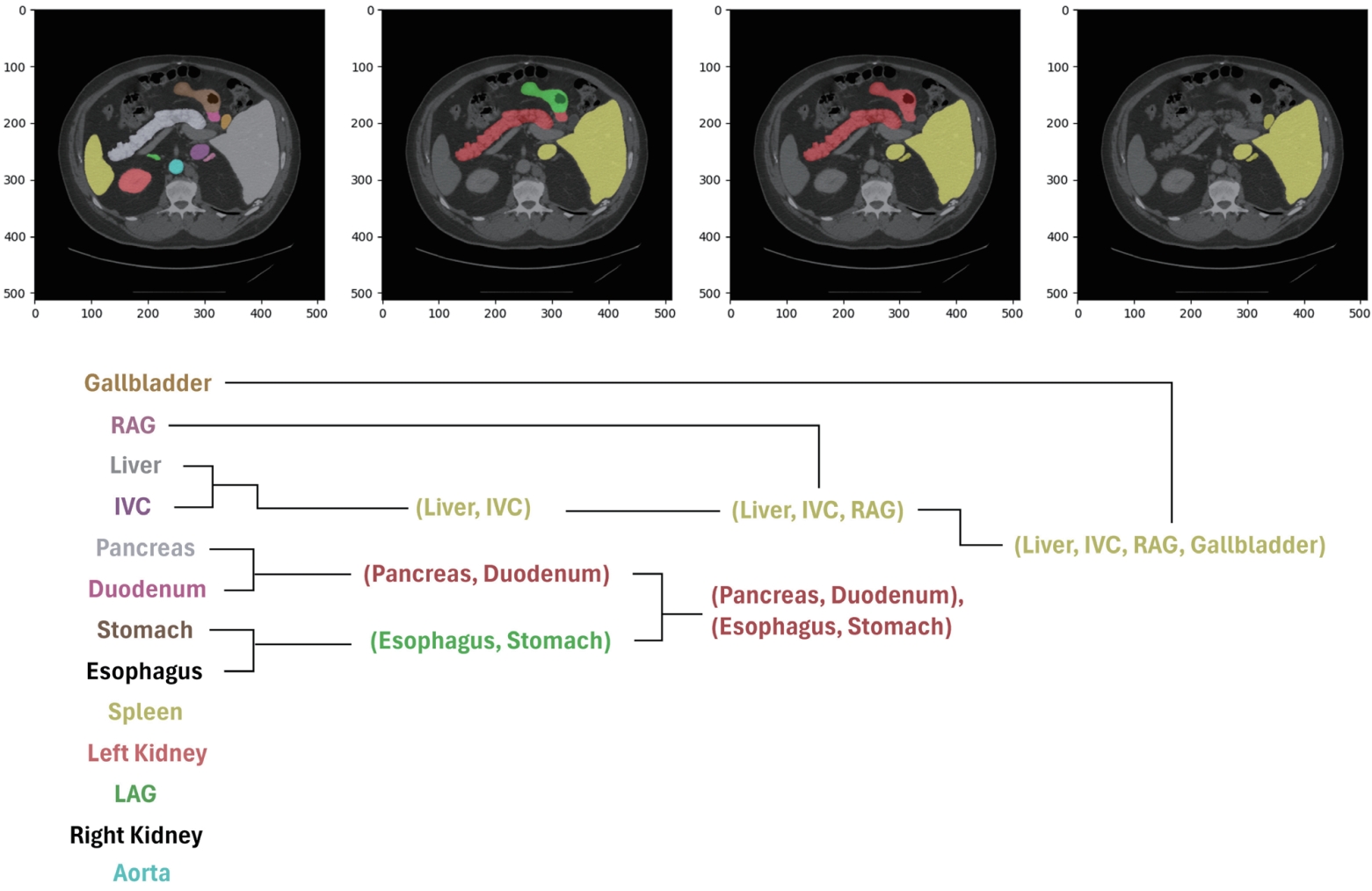

However, in medical imaging, it is often difficult to define the relationships between organs based on a semantic hierarchy. Instead, spatial cues directly observed in the images, such as anatomical location or adjacency, are more suitable for establishing the hierarchy. Based on these observations, we propose a new approach that defines the hierarchy by leveraging organ adjacency and guides the model to learn it. This strategy is data-driven and does not rely on pre-defined semantic knowledge. It naturally captures anatomical relationships that frequently appear in CT images, such as the spatial proximity between the liver and the inferior vena cava (IVC). By explicitly learning such structures, the model is able to reduce inter-organ confusion and achieve more consistent and accurate segmentation results across different patient cohorts.

To quantify organ adjacency, we apply binary dilation operations to each organ’s ground-truth mask, expanding its boundaries by one pixel in eight directions. We then calculate the number of overlapping pixels between the dilated mask and other organ masks, which reflects how often two organs share boundaries in the actual image. For example, if the dilated mask of the IVC significantly overlaps with the liver mask, this indicates strong adjacency between the two organs.

Using the adjacency scores computed for every organ pair, we perform hierarchical clustering, where highly adjacent organs are grouped first. This results in a tree-like structure based on pixel-level adjacency, as illustrated in

Fig. 9. Examples of early merged groups include liver–IVC and stomach–esophagus, which often share anatomical boundaries.

To ensure that the model’s predicted class probabilities respect this hierarchical structure, we introduce hierarchical constraints during training. Specifically, we enforce T-properties between parent and child classes:

• Positive T-constraint: If a pixel has a high probability of belonging to a child class (e.g., liver with probability 0.8), its probability of belonging to the corresponding parent group (e.g., liver + IVC) must be equal to or higher.

• Negative T-constraint: Conversely, if the parent group has a low probability (e.g., 0.2), none of its children should have higher probabilities.

This learning strategy allows the model to move beyond independent pixel-wise classification and instead infer predictions that reflect the anatomical adjacency between organs.

To validate the proposed approach, we conducted experiments on the same FLARE22 dataset under identical conditions as the previous methods. As shown in

Table 5, the proposed method achieved a 1.27% improvement in mean DSC over a conventional 2D U-Net baseline.

3. Comparative study of learning strategies for generalized multi-organ segmentation

Most recent studies on medical image segmentation models have focused either on training a limited subset of organs within a single dataset or developing separate models for different datasets. However, these approaches lack generalizability and scalability, which are essential for real-world clinical deployment. As alternatives, two learning strategies have recently gained attention: continual learning and multi-dataset learning.

Continual learning enables the model to incrementally learn new organ or lesion classes without revisiting the previously used data. For instance, if a model has been trained on liver and kidney data, continual learning allows the model to expand and learn to segment the spleen using only the spleen data—without re-accessing the liver or kidney datasets. This approach is especially advantageous when patient data access is restricted. However, a major challenge is the risk of catastrophic forgetting , where the model forgets previously learned knowledge while adapting to new data.

On the other hand, multi-dataset learning involves training a unified model on multiple datasets collected from different sources simultaneously. For example, combining the publicly available abdominal CT datasets FLARE22 [

37] and BTCV [

39] allows the model to learn a wider variety of anatomical structures and imaging conditions, which can enhance both segmentation accuracy and generalizability. However, this approach assumes that simultaneous access to all datasets is possible during training.

Thus, the choice between these strategies depends on application context and data availability. Continual learning offers a practical solution when dataset access is limited and incremental updates are needed, while multi-dataset learning provides the best performance when full access to diverse datasets is available.

In this study, we benchmarked both strategies under the same experimental conditions by referencing representative approaches: Zhang et al. [

8] for continual learning and Ulrich et al. [

7] for multi-dataset learning. As summarized in

Table 6, the multi-dataset learning approach achieved the highest average DSC (90.58%), outperforming continual learning (86.54%) and conventional single-dataset training (FLARE22: 87.98%, BTCV: 79.59%). These results suggest that multi-dataset learning provides more accurate and consistent segmentation performance by leveraging diverse anatomical structures and imaging characteristics across datasets.

FUTURE WORK

In future research on the automation of body composition analysis using abdominal CT, we plan to actively utilize and expand upon our previously developed technical achievements, including vertebral-level localization and identification, body composition segmentation, and multi-organ segmentation.

For early cancer detection, we aim to develop a novel 3D CT anomaly detection model based on our existing multi-level vertebral body composition analysis algorithm. This system is designed to automatically and quantitatively detect subtle changes in body composition at an early stage from CT scans of actual cancer patients.

In the pediatric CT analysis domain, we plan to leverage adult body composition analysis techniques to build a dedicated pediatric CT database and develop pediatric-specific body composition analysis models. Given the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases due to childhood obesity, this field is expected to have significant clinical demand. Furthermore, pediatric CT-based body composition indices are anticipated to aid in the early identification of cancer. To this end, we will apply transfer learning and fine-tuning techniques to adapt adult-trained models, thereby enabling early assessment of body composition changes related to pediatric obesity and chronic conditions.

Recent advances in DL have highlighted the importance of integrating imaging data with clinical information to better reflect real-world medical contexts. Building on our work in medical image segmentation and quantification, we aim to develop a multimodal algorithm that combines CT images with textual data such as electronic medical records, physician notes, and clinical histories. This research ultimately seeks to establish a practical platform that supports context-aware clinical decision-making, with the aim of more comprehensively reflecting the clinical context.

Additionally, through the analysis and prediction modeling of the relationship between cancer and body composition, we plan to investigate in detail the distributional differences in body composition between high-risk cancer groups and healthy controls, as well as their correlation with cancer incidence. Leveraging our existing framework for body composition analysis, we will validate the effectiveness of specific body composition indicators in early cancer screening and risk assessment.

Together, these research directions are designed to extend our current technical foundation through the integration of new analytical methods and clinical data. Ultimately, they aim to evolve into next-generation body composition analysis technologies with greater scalability and practical utility in real-world clinical settings.

DISCUSSION

Deep learning–based medical image analysis methods have been actively investigated, yielding notable technical advances. However, for clinical application, considerations beyond simple performance metrics are required. In particular, explainability and generalizability are regarded as important factors for building trust in models and enabling their widespread adoption in clinical practice. This section discusses remaining challenges and future perspectives with a focus on these two aspects.

Explainability

Even when deep learning models achieve high accuracy, their clinical use can be strengthened if they also provide evidence for why the results were produced. This need has driven active research on explainable artificial intelligence (XAI). Earlier studies mainly proposed methods such as visualizing the spatial regions highlighted by CNNs through gradient-based techniques, or presenting attention maps from attention-based models as heatmaps [

40,

41]. These approaches help build confidence in interpretation by intuitively showing the basis for predictions.

More recently, approaches such as concept-based reasoning, which infers the anatomical concepts referenced by the model, and prototype-based interpretability, which justify predictions by comparison with representative examples, have been explored [

42,

43]. Some studies have also pointed out that models may rely on clinically irrelevant shortcuts or spurious correlations, and to mitigate this problem, interactive XAI frameworks have been proposed that allow physicians to exclude inappropriate concepts or introduce new criteria [

44]. Such methods refine model decision-making and support its evolution into a more reliable clinical aid.

These approaches can also be directly applied to abdominal CT–based body composition analysis. For example, in vertebral level identification, the model could highlight the anatomical landmarks it used as evidence. In multi-organ segmentation, ambiguous regions could be displayed as uncertainty maps, enabling physicians to quickly review and correct them. This would allow medical professionals to more easily verify and adjust model outputs, thereby enhancing trust and adoption in clinical workflows. Furthermore, explainability techniques could be extended to early cancer detection. By visually highlighting the reasons for suspecting cancer and the lesion areas considered, clinicians could place greater trust in the results, providing practical support for early diagnosis and treatment decisions.

Generalizability

Models that perform well only on single-institution datasets or narrowly defined tasks face substantial limitations for clinical deployment, as domain shift caused by differences in CT scanners, imaging protocols, and patient populations is well recognized. Therefore, the ability to maintain robust performance across diverse environments is a key requirement for clinical adoption.

To address this issue, recent studies have focused on universal medical image segmentation, which spans multiple imaging modalities and body regions [

45,

46]. For instance, Gao et al. [

47] demonstrated that learning priors derived from the diversity and commonalities of multi-institutional, multi-modality datasets can improve generalization performance by leveraging synergies across tasks.

This trend has important implications for abdominal CT–based body composition analysis. It underscores the feasibility of developing universal models resilient to variations in hospitals, imaging conditions, and patient populations. Specifically, multi-dataset learning across diverse datasets can enhance cross-dataset robustness, while continual learning enables the gradual integration of new patient cohorts without compromising existing performance. In addition, incorporating context-prior learning to help models recognize modality- and task-specific characteristics could further improve generalization.

Such advances can help overcome the heterogeneity of real-world clinical environments, substantially improving the generalizability of abdominal CT–based body composition analysis and enhancing its potential for clinical use.

CONCLUSION

This review outlines strategies for achieving full-cycle automation and broad applicability in clinical settings by connecting and integrating DL-based approaches for body composition analysis using abdominal CT. The proposed methods automatically generate anatomical distribution maps and significantly enhance analytical accuracy and reproducibility by addressing real-world challenges such as limited annotations, data heterogeneity, and structural complexity.

This technological foundation extends beyond the automation of body composition measurement, offering scalability to a wide range of clinical and research applications, including large-scale cohort studies, personalized treatment planning, and longitudinal monitoring of organ changes.

NOTES

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

-

FUND

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00360226).

-

ETHICS STATEMENT

None.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

I.A. performed the vertebrae localization and identification research; S.A. and M.S.K. carried out the body composition segmentation research; H.L. and A.I. conducted the multi-organ segmentation research; H.L., S.A., M.S.K., I.A., and A.I. prepared the original draft; H.L. compiled and edited the manuscript; Y.R.L., S.Y.P., W.Y.T. supervised the clinical aspects of the project; S.K.J. critically reviewed and edited the manuscript and supervised the overall project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Figure 1.Anatomical distribution map visualized in 3D, based on our model’s predictions for body composition and multi-organ segmentation on abdominal CT scans from Kyungpook National University Hospital. CT, computed tomography.

Figure 2.Architecture of L3 slice detector for L3 vertebrae slice detection. The CT scan volume input undergoes a series of convolutional and max pooling layers across three encoder stages. The extracted features are flattened and passed through fully connected layers, ending in a binary classification via a sigmoid function [

12]. CT, computed tomography.

Figure 3.Overview of the proposed vertebra identification framework. (A) DRR images are generated from CT scans. (B) A contrastive learning module is trained on DRR view pairs to enforce view-invariant feature representation. (C) A ResU-Net-based localization network estimates vertebra heatmaps, and a deep peak clustering algorithm extracts vertebral centroids from the predicted heatmaps. (D) The identification network, based on ResU-Net with a Multi-Dilated Context Refinement (MDCR) block, assigns vertebra labels. (E) The MDCR block employs multi-dilated depth-wise separable convolutions followed by point- wise fusion to aggregate both local and global contextual information efficiently [

3]. DRR, digitally reconstructed radiograph; CT, computed tomography.

Figure 4.Vertebral localization and identification results across multiple DRR views. Red and green crosses indicate ground truth and predicted centroids, respectively. A cascading error is observed as T8 is misidentified as T1, resulting in shifted labels [

3]. DRR, digitally reconstructed radiograph.

Figure 5.Overview of the proposed TED-Net architecture. (A) Consists of twin encoder-decoder network wherein supervised loss is used for source domain and unsupervised loss terms are used for target domain. (B) Res-Conv block of TED-Net [

4].

Figure 6.Input-Output Structure Comparison of 2D/2.5D/3D.

Figure 7.Overview of our 2.5D segmentation framework incorporating the proposed dual cross attention and class-level representation alignment across adjacent slices [

5].

Figure 8.Illustration of class-wise prototype learning [

5].

Figure 9.Hierarchy based on pixel adjacency in the FLARE22 dataset [

6]. IVC, inferior vena cava; RAG, right adrenal gland; LAG, left adrenal gland.

Table 1.Performance comparison for L3 slice detector using single and multi-channel inputs on KNUH abdominal CT dataset

Table 1.

|

Single |

Multi |

Class |

Precision↑ |

Recall↑ |

Specificity↑ |

F1-score↑ |

|

√ |

|

L3 |

26.28 |

60.00 |

99.30 |

36.55 |

|

|

Non-L3 |

99.83 |

99.30 |

60.00 |

99.57 |

|

√ |

L3 |

94.12 |

80.00 |

99.94 |

86.49 |

|

|

Non-L3 |

99.78 |

99.94 |

80.00 |

99.86 |

Table 2.Performance comparison of localization error and identification rate on the VerSe 2019 dataset

Table 2.

|

Method |

L-Error↓ |

Id-Rate↑ |

|

Payer et al. [22] |

4.27 |

95.65 |

|

Sekuboyina et al. [23] |

5.17 |

89.97 |

|

Wu et al. [21] |

1.79 |

98.12 |

|

Ours |

1.64±0.02 |

86.32±0.50 |

Table 3.Performance comparison between transfer learning and the proposed cross-domain consistency learning on KNUH body composition dataset

Table 3.

|

Class |

DSC↑ |

IoU↑ |

|

TL |

CDCL |

TL |

CDCL |

|

BKG |

98.90±0.32 |

98.73±0.25 |

97.84±0.49 |

97.53±0.48 |

|

MUS |

90.72±0.88 |

89.76±0.42 |

83.64±1.19 |

82.43±0.62 |

|

IMAT |

67.11±2.88 |

78.59±1.83 |

51.44±3.24 |

65.55±2.42 |

|

SAT |

95.55±0.63 |

96.88±0.37 |

91.91±1.03 |

94.40±0.63 |

|

VAT |

87.64±3.84 |

89.06±3.09 |

82.49±5.05 |

84.68±3.86 |

|

AVG |

85.26±1.52 |

88.57±1.11 |

77.37±1.88 |

81.77±1.47 |

Table 4.Performance comparison of ablation and existing methods on FLARE22 dataset

Table 4.

|

Method |

mDSC↑ |

mIoU↑ |

|

2D U-Net |

88.35 |

86.81 |

|

2.5D U-Net |

88.02 |

85.92 |

|

Hung et al. [34] |

90.52 |

88.42 |

|

Kumar et al. [35] |

90.34 |

88.27 |

|

DCA |

90.55 |

88.48 |

|

DCA+PL |

90.73 |

88.64 |

|

DCA+SC |

90.94 |

88.62 |

|

DCA+PL+SC |

91.84 |

89.65 |

Table 5.Performance comparison between conventional segmentation and the proposed pixel adjacency-based hierarchical segmentation on FLARE22 dataset

Table 5.

|

Class |

DSC↑ |

IoU↑ |

|

CS |

PAHS |

CS |

PAHS |

|

Liver |

92.73 |

95.58 |

91.34 |

94.25 |

|

Right kidney |

94.47 |

90.92 |

93.40 |

89.99 |

|

Spleen |

94.26 |

90.30 |

93.53 |

89.51 |

|

Pancreas |

82.85 |

82.64 |

78.99 |

78.64 |

|

Aorta |

93.52 |

93.18 |

90.86 |

90.45 |

|

Inferior vena cava |

83.76 |

88.62 |

78.89 |

84.68 |

|

Right adrenal gland |

81.61 |

89.63 |

80.11 |

87.92 |

|

Left adrenal gland |

87.24 |

88.09 |

85.69 |

86.34 |

|

Gallbladder |

92.40 |

94.02 |

91.36 |

92.92 |

|

Esophagus |

88.88 |

93.30 |

87.00 |

91.42 |

|

Stomach |

90.38 |

89.27 |

88.31 |

87.12 |

|

Duodenum |

77.68 |

83.37 |

73.77 |

79.32 |

|

Left kidney |

95.32 |

86.12 |

94.24 |

84.82 |

|

AVG |

88.35 |

89.62 |

86.81 |

87.49 |

Table 6.Performance evaluation using DSC for three training schemes: multi-dataset, continual, and conventional approaches on FLARE22 and BTCV datasets across different organs

Table 6.

|

Class |

Conventional |

Continual |

Multi-dataset |

|

FLARE22 |

BTCV |

FLARE22/BTCV |

FLARE22/BTCV |

|

Liver |

94.94 |

89.91 |

87.44 |

93.54 |

|

Right kidney |

93.49 |

88.23 |

84.77 |

96.58 |

|

Spleen |

92.97 |

89.23 |

92.97 |

95.06 |

|

Pancreas |

79.74 |

81.09 |

76.22 |

88.09 |

|

Aorta |

95.45 |

95.30 |

92.23 |

95.12 |

|

Inferior vena cava |

92.61 |

91.00 |

87.44 |

90.32 |

|

Right adrenal gland |

78.34 |

64.25 |

84.06 |

83.46 |

|

Left adrenal gland |

77.21 |

63.75 |

89.71 |

79.70 |

|

Gallbladder |

86.02 |

68.68 |

86.02 |

94.43 |

|

Esophagus |

88.08 |

79.56 |

73.19 |

93.62 |

|

Stomach |

91.13 |

80.60 |

95.33 |

91.58 |

|

Duodenum |

80.54 |

63.72 |

84.06 |

87.58 |

|

Left kidney |

93.26 |

89.82 |

89.71 |

95.04 |

|

Portal vein |

- |

69.20 |

88.46 |

84.03 |

|

AVG |

87.98 |

79.59 |

86.54 |

90.58 |

REFERENCES

- 1. Bennett JP, Lim S. The critical role of body composition assessment in advancing research and clinical health risk assessment across the lifespan. J Obes Metab Syndr 2025;34:120-137.

- 2. Mai DVC, Drami I, Pring ET, et al. A systematic review of automated segmentation of 3D computed tomography scans for volumetric body composition analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023;14:1973-1986.

- 3. Ahmad I, Ali S, Jung SK. Multi-view learning for vertebrae identification in digitally reconstructed radiographs. In: Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Human System Interaction (HSI); 2025; Piscataway (NJ): IEEE, 2025.

- 4. Ali S, Lee YR, Park SY, Tak WY, Jung SK. Unsupervised domain adaptation by cross-domain consistency learning for CT body composition. Mach Vis Appl 2025;36:27.

- 5. Lee H, Lee YR, Park SY, Tak WY, Jung SK. Inter-slice dual cross attention and class-level alignment for 2.5D medical image segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Visual and Signal-Based Systems (AVSS); 2025; Piscataway (NJ): IEEE, 2025.

- 6. Lee H, Kim IS, Lee YR, Park SY, Tak WY, Jung SK. Hierarchical image segmentation via pixel adjacency. In: Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Smart Media & Applications (SMA 2024); 2024; Gwangju: Korean Institute of Smart Media, 2024.

- 7. Ulrich C, Smith T, Lee H, et al. Multitalent: a multi-dataset approach to medical image segmentation. In: Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2023; Cham (CH): Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023.

- 8. Zhang Y, Wang J, Liu X, et al. Continual learning for abdominal multi-organ and tumor segmentation. In: Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2023; Cham (CH): Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023.

- 9. Asad I, Iftikhar A, Ali S, Jung SK. From single to unified training: evaluating multi-organ segmentation techniques. In: International Workshop on Frontiers of Computer Vision (IW-FCV); 2025; Cham (CH): Springer, 2025.

- 10. Mitsiopoulos N, Baumgartner RN, Heymsfield SB, Lyons W, Gallagher D, Ross R. Cadaver validation of skeletal muscle measurement by magnetic resonance imaging and computerized tomography. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1998;85:115-122.

- 11. Ali S, Lee YR, Park SY, Tak WY, Jung SK. Volumetric body composition through cross-domain consistency training for unsupervised domain adaptation. In: Advances in Visual Computing. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 14361; Cham (CH): Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023:289-299.

- 12. Ahmad I, Ali S, Lee YR, Park SY, Tak WY, Jung SK. Pixel-unshuffled multi-channel approach for efficient L3 slice detection in CT scans. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Research in Adaptive and Convergent Systems (RACS 2024); 2024; New York (NY): ACM, 2024.

- 13. Brath MSG, Lutz A, Müller D, et al. Association between thoracic and third lumbar CT-derived muscle mass and density in Caucasian patients without chronic disease: a proof-of-concept study. Eur Radiol Exp 2023;7:26.

- 14. Zopfs D, Linxweiler J, Gaudin RA, et al. Two-dimensional CT measurements enable assessment of body composition on head and neck CT. Eur Radiol 2022;32:6427-6434.

- 15. Cheng P, Yang Y, Yu H, He Y. Automatic vertebrae localization and segmentation in CT with a two-stage Dense-U-Net. Sci Rep 2021;11:22156.

- 16. Windsor R, Gordon L, Halliday J, et al. Automated detection, labelling and radiological grading of clinical spinal MRIs. Sci Rep 2024;14:14993.

- 17. Wang F, Zhao H, Wang Y, et al. Automatic vertebra localization and identification in CT by spine rectification and anatomically-constrained optimization. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021; Piscataway (NJ): IEEE, 2021.

- 18. Sekuboyina A, Bayat A, Husseini ME, et al. VerSe: a vertebrae labelling and segmentation benchmark for multi-detector CT images. Med Image Anal 2021;73:102166.

- 19. Shi W, Caballero J, Huszár F, et al. Real-time single image and video super-resolution using an efficient sub-pixel convolutional neural network. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016; Las Vegas (NV): IEEE, 2016.

- 20. Rodriguez A, Laio A. Clustering by fast search and find of density peaks. Science 2014;344:1492-1496.

- 21. Wu H, Zhang J, Fang Y, et al. Multi-view vertebra localization and identification from CT images. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI); Cham (CH): Springer, 2023:136-145.

- 22. Payer C, Stern D, Bischof H, et al. Coarse to fine vertebrae localization and segmentation with spatial configuration-net and U-Net. In: Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2020); Setúbal (PT): SCITEPRESS, 2020:124-133.

- 23. Sekuboyina A, Rempfler M, Kukacka J, et al. Btrfly net: vertebrae labelling with energy-based adversarial learning of local spine prior. In: Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2018; Cham (CH): Springer, 2018:649-657.

- 24. Lam BCC, Koh GCH, Chen C, et al. Comparison of body mass index, body adiposity index, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio and waist-to-height ratio as predictors of cardiovascular disease risk factors in an adult population in Singapore. PLoS One 2015;10:e0122985.

- 25. Huxley R, Mendis S, Zheleznyakov E, Reddy S, Chan J. Body mass index, waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio as predictors of cardiovascular risk: a review of the literature. Eur J Clin Nutr 2010;64:16-22.

- 26. Thomas DM, Crofford I, Scudder J, Oletti B, Deb A, Heymsfield SB. Updates on methods for body composition analysis: Implications for clinical practice. Curr Obes Rep 2025;14:8.

- 27. Ma D, Yan J, Wang Z, et al. Comprehensive validation of automated whole body skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and bone segmentation from 3D CT images for body composition analysis: towards extended body composition. arXiv [Preprint] 2021 Jun 1. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/2106.00652

- 28. Jung M, Lee H, Kim S, et al. Deep learning-based body composition analysis from whole-body magnetic resonance imaging to predict all-cause mortality in a large western population. EBioMedicine 2024;110:1-12.

- 29. Magudia K, Kwan BM, Hager B, et al. Population-scale CT-based body composition analysis of a large outpatient population using deep learning to derive age-, sex-, and race-specific reference curves. Radiology 2021;2:319-329.

- 30. Erdur AC, Ozkan B, Pohlmann A, et al. Deep learning for autosegmentation for radiotherapy treatment planning: State-of-the-art and novel perspectives. Strahlenther Onkol 2025;201:236-254.

- 31. Kutaiba N, Alabousi M, Alqahtani S, et al. The impact of hepatic and splenic volumetric assessment in imaging for chronic liver disease: a narrative review. Insights Imaging 2024;15:146.

- 32. Zhang Y, Wang X, Li Q, et al. SequentialSegNet: combination with sequential feature for multi-organ segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR). Piscataway (NJ): IEEE, 2018.

- 33. Hung ALY, Chen W, Zhao Y, et al. CSAM: a 2.5D cross-slice attention module for anisotropic volumetric medical image segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV). Piscataway (NJ): IEEE, 2024.

- 34. Hung ALY, Chen W, Zhao Y, et al. CAT-Net: a cross-slice attention transformer model for prostate zonal segmentation in MRI. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2022;42:291-303.

- 35. Kumar A, Singh P, Reddy M, et al. A flexible 2.5D medical image segmentation approach with in-slice and cross-slice attention. Comput Biol Med 2024;182:109173.

- 36. Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T. U-Net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In: Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI). Cham (CH): Springer, 2015:234-241.

- 37. Ma J, Li X, Zhang Y, et al. Unleashing the strengths of unlabelled data in deep learning-assisted pan-cancer abdominal organ quantification: the FLARE22 challenge. Lancet Digit Health 2024;6:e815-e826.

- 38. Li L, Wang X, Zhang H, et al. Deep hierarchical semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway (NJ): IEEE, 2022.

- 39. Landman B, Xu Z, Iglesias J, et al. MICCAI multi-atlas labeling beyond the cranial vault—workshop and challenge. In: Proceedings of the MICCAI Multi-Atlas Labeling Beyond Cranial Vault—Workshop Challenge. 2015. p.12.

- 40. Selvaraju RR, Cogswell M, Das A, et al. Grad-CAM: visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision. Piscataway (NJ): IEEE, 2017.

- 41. Playout C, Duval R, Boucher MC, et al. Focused attention in transformers for interpretable classification of retinal images. Med Image Anal 2022;82:102617.

- 42. Vats A, Pedersen M, Mohammed A, et al. Concept-based reasoning in medical imaging. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg 2023;18:845-856.

- 43. Singh M, Vivek BS, Gubbi J, et al. Prototype-based interpretable model for glaucoma detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops. Piscataway (NJ): IEEE, 2024.

- 44. Huy TD, Tran SK, Phan N, et al. Interactive medical image analysis with concept-based similarity reasoning. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Piscataway (NJ): IEEE, 2025.

- 45. Butoi V, Vilesov A, Popescu M, et al. UniverSeg: universal medical image segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. Piscataway (NJ): IEEE, 2023.

- 46. Liu J, Zhang Y, Chen JN, et al. Clip-driven universal model for organ segmentation and tumor detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. Piscataway (NJ): IEEE, 2023.

- 47. Gao Y, Li Q, Wang H, et al. Training like a medical resident: context-prior learning toward universal medical image segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Piscataway (NJ): IEEE, 2024.